The Archive who Breathes

On the circumstances and consequences of archival gaps

essay by Hannah Dawn Henderson – 30 nov. 2022topic: Bodies and Breath: Embodied Research & Writing

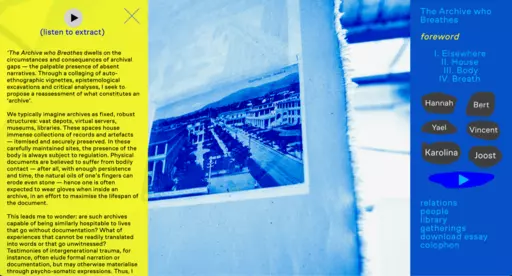

The Archive who Breathes is a project by Hannah Dawn Henderson, commissioned by ArtEZ Studium Generale, on the circumstances and consequences of archival gaps — the palpable presence of absent narratives. Here you can find Hannah's introduction on the project. But above all, you are invited to take a look at the website that belongs to this project. Specially designed by Lotte Lara Schröder, you can meander through a collection of annotations, footnotes and marginalia by Hannah's friends: website.

You can either download her essay The Archive who Breathes as a PDF or read and meander through it on her website. We recommend both!

You can either download her essay The Archive who Breathes as a PDF or read and meander through it on her website. We recommend both!

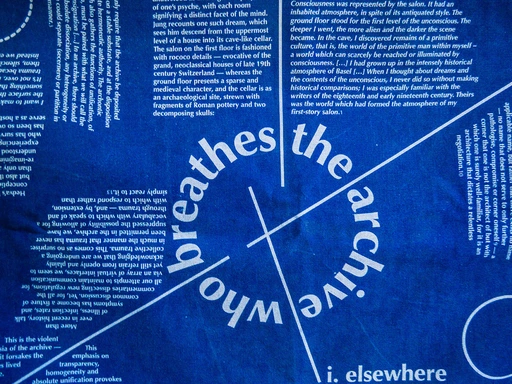

The Archive who Breathes dwells on the circumstances and consequences of archival gaps — the palpable presence of absent narratives. Through a collaging of auto-ethnographic vignettes, epistemological excavations and critical analyses, I seek to propose a reassessment of what constitutes an ‘archive’.

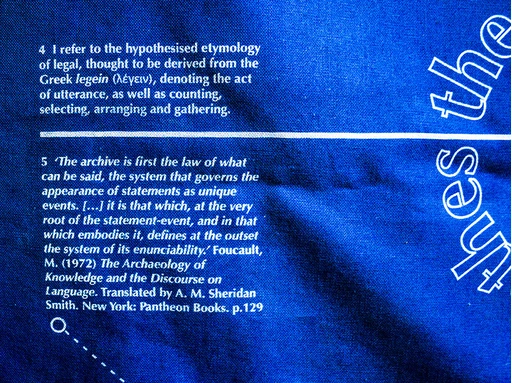

We typically imagine archives as fixed, robust structures: vast depots, virtual servers, museums, libraries. These spaces house immense collections of records and artefacts — itemised and securely preserved. In these carefully maintained sites, the presence of the body is always subject to regulation. Physical documents are believed to suffer from bodily contact — after all, with enough persistence and time, the natural oils of one’s fingers can erode even stone — hence one is often expected to wear gloves when inside an archive, in an effort to maximise the lifespan of the document.

This leads me to wonder: are such archives capable of being similarly hospitable to lives that go without documentation? What of experiences that cannot be readily translated into words or that go unwitnessed? Testimonies of intergenerational trauma, for instance, often elude formal narration or documentation, but may otherwise materialise through psycho-somatic expressions. Thus, I propose that the body can also be understood as an archival vessel — a site of registration — both hostage and host to unvoiced histories.’

We typically imagine archives as fixed, robust structures: vast depots, virtual servers, museums, libraries. These spaces house immense collections of records and artefacts — itemised and securely preserved. In these carefully maintained sites, the presence of the body is always subject to regulation. Physical documents are believed to suffer from bodily contact — after all, with enough persistence and time, the natural oils of one’s fingers can erode even stone — hence one is often expected to wear gloves when inside an archive, in an effort to maximise the lifespan of the document.

This leads me to wonder: are such archives capable of being similarly hospitable to lives that go without documentation? What of experiences that cannot be readily translated into words or that go unwitnessed? Testimonies of intergenerational trauma, for instance, often elude formal narration or documentation, but may otherwise materialise through psycho-somatic expressions. Thus, I propose that the body can also be understood as an archival vessel — a site of registration — both hostage and host to unvoiced histories.’

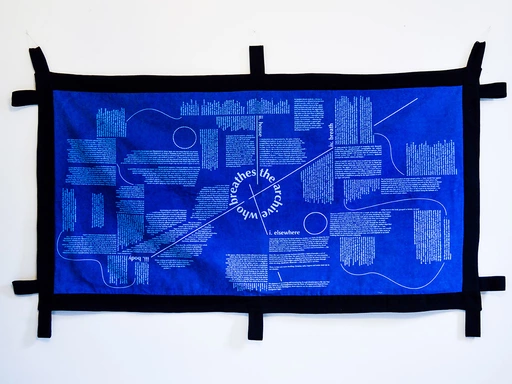

The essay was collectively performed with friends and fellow-artists Ratu R Saraswati (Saras) and Arefeh Riahi at PrintRoom in Rotterdam, where a printed version of the essay was presented, produced in the format of a blueprint, a medium that, on account of its unstable, light-sensitive nature, is capable of both forgetting and recollecting itself. Hannah has generously gifted one copy of the printed essay to the library at ArtEZ, Arnhem, where you are invited to read and engage it, next time you are there.