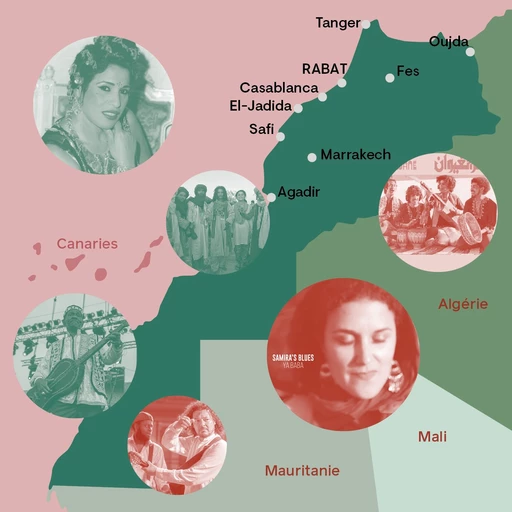

Samira Dainan explores the power of Moroccan roots music

Radio ArtEZ, season 3, episode 12

blog by Samira Dainan – 23 jun. 2020topic: Home & Belonging

This list has been carefully curated and written by musician and writer Samira Dainan in addition to the personal and lyrical journey through Morocco and part of the Sahara. This list is "an ode to the musicians of the Maghreb," by a musician who with her rigorous craft has revitalized the histories and tales of Amazigh, Arabic, African, and Sufi music, away from the Eurocentric gaze.

I. Classical Arabic Music

Divas from the 50s and 60s like Oum Kalthoum (Egypt) and Fairouz (Libanon) are great examples to follow in this music style. Both were extremely popular in subsequent decades and both are considered legends of secular Arabic music. Much Arabic music is characterized by an emphasis on melody and rhythm, as opposed to harmony. The focus of this music lies on the scales, or Maqamat. The Arabic Maqamat are a system of melodic modes used in traditional Arabic music, which is mainly melodic. Both compositions and improvisations in traditional Arabic music are based on the maqam system. The main difference between the Western chromatic scale and the Arabic scales is the existence of many in-between notes, which are sometimes referred to as quarter tones. Maqamat can be realized with either vocal or instrumental music, and do not include a rhythmic component. The development of Arabic music has extremely deep roots in Arabic poetry dating back to the pre-Islamic period. Al-Kindi (801–873 AD) was the first great theoretician of Arabic music. He discussed cosmological connotations of music. In one of his treaties the word musiqa was used for the first time in Arabic, which today means music.

Divas from the 50s and 60s like Oum Kalthoum (Egypt) and Fairouz (Libanon) are great examples to follow in this music style. Both were extremely popular in subsequent decades and both are considered legends of secular Arabic music. Much Arabic music is characterized by an emphasis on melody and rhythm, as opposed to harmony. The focus of this music lies on the scales, or Maqamat. The Arabic Maqamat are a system of melodic modes used in traditional Arabic music, which is mainly melodic. Both compositions and improvisations in traditional Arabic music are based on the maqam system. The main difference between the Western chromatic scale and the Arabic scales is the existence of many in-between notes, which are sometimes referred to as quarter tones. Maqamat can be realized with either vocal or instrumental music, and do not include a rhythmic component. The development of Arabic music has extremely deep roots in Arabic poetry dating back to the pre-Islamic period. Al-Kindi (801–873 AD) was the first great theoretician of Arabic music. He discussed cosmological connotations of music. In one of his treaties the word musiqa was used for the first time in Arabic, which today means music.

(Andalusian muwashah. The song is romantic poetry that recounts the beauties of the singer’s beloved. “When she starts to move, amen, her beauty fascinates us. The movements are like a tree branch dancing in the wind”.)

In Morocco you can find classical Andalusian music. Believed to have originated in Cordoba in the ninth century, classical Andalusian music made its way to Morocco during the mass resettlement of the Sephardi Jewish and Muslim population from Al Andalus following the Spanish Inquisition. Several northern Moroccan cities – including Fes, Tetouan, Tangier and Chefchaouen – are home to world-renowned Andalusian multi-piece orchestras.

Andalusian music is extremely complicated in musical structure, and its lyrics are characterized by the strict use of the Andalusian dialect or classical Arabic and by the construction of verse in the style of classical poetry.

Andalusian music is extremely complicated in musical structure, and its lyrics are characterized by the strict use of the Andalusian dialect or classical Arabic and by the construction of verse in the style of classical poetry.

II. Gnawa music

Mahmoud Gania - Chabakouriya // Essaouira 2015

Gnawa Sufi brotherhoods (tariqas) are common in Morocco, and music is an integral part of their spiritual tradition, in contrast to most other forms of Islam, which do not use music. Sufi music is an attempt at reaching a trance state which inspires mystical ecstasy.

The Gnawa are descendants of Black Africans from Senegal, Sudan, Ghana and brought their music to Morocco through the Sahara. The Gnawa appeared in the 16th century. During the conquest of Sudan, Ahmed El Mansour Dahbi set up the first trading and cultural links between Timbuktu, near Zagora, where Bekkas comes from, and Marrakech.

The Gnawa claim descent from the Ethiopian muezzin Sidi Bilal. In song lyrics, they refer to their origins among the Bambara, Fulani, and Haussa, and history points to a large influx of Gnawa primarily in the Niger riverbend area of Mali and Niger. Gnawa ceremonies are used to protect against mental illness, diseases and malicious spirits and are related to Sub-Saharan African ceremonies. The Gnawa lila, mostly led by a maâllem, or master, is a rich ceremony of song, music, dance, costume, and incense that takes place over the course of an entire night, ending around dawn.

The guembri is the main Gnawa instrument, with three strings and made of goatskin, and native to Sub-Saharan Africa, although it merged with Moroccan traditional music. It is distinctive for its rhythmic repetitiveness, its almost arrhythmic swing, and a relentless conversation between the main vocalist and the rest of the musicians, making it deservedly recognized for its capacity to stimulate the listener and induce him/her to a state of trance, along with the performers. The guembri is the only instrument in the Gnawa genre that has a low harmonic range, and it is frequently and correctly compared to a bass guitar by western ears.

Maalem Mahmoud Gania was one of Morocco's most famous Gnawa musicians (1951- 2015 Essaouira). Mahmoud Gania, who belonged to an artistic family that traces its ancestry back to Mali, played a major role in developing Gnawa music in Morocco. He was a respected singer and guembri player and he recorded for both domestic and foreign labels, and collaborated with numerous musicians (e.g. Santana).

With significant tourism and artistic exchanges between Morocco and the West, Gnawa music became internationalized thanks to influences outside the Maghreb, such as Youssou 'n Dour, Wayne Shorter and Randy Weston, who often call upon Gnawa musicians in their compositions. Since 1992, the Gnawa of Morocco have seen their status change, with the creation of the Gnaoua & World Music Festival, boosting their recognition on the international scene.

An example of a Gnawa musician in the new tradition is Abdelmajid Bekkas.

Majid Bekkas is a multi-instrumentalist, singer and composer, born and still living in Sale, Morocco. He learnt Gnawa music through the teachings

of the master/ maâllem Ba Houmane. For many years, Majid Bekkas worked on crossovers with big names in world music and jazz.

Here you find him singing a more traditional Gnawa song about a leader of the Bambara:

The Gnawa are descendants of Black Africans from Senegal, Sudan, Ghana and brought their music to Morocco through the Sahara. The Gnawa appeared in the 16th century. During the conquest of Sudan, Ahmed El Mansour Dahbi set up the first trading and cultural links between Timbuktu, near Zagora, where Bekkas comes from, and Marrakech.

The Gnawa claim descent from the Ethiopian muezzin Sidi Bilal. In song lyrics, they refer to their origins among the Bambara, Fulani, and Haussa, and history points to a large influx of Gnawa primarily in the Niger riverbend area of Mali and Niger. Gnawa ceremonies are used to protect against mental illness, diseases and malicious spirits and are related to Sub-Saharan African ceremonies. The Gnawa lila, mostly led by a maâllem, or master, is a rich ceremony of song, music, dance, costume, and incense that takes place over the course of an entire night, ending around dawn.

The guembri is the main Gnawa instrument, with three strings and made of goatskin, and native to Sub-Saharan Africa, although it merged with Moroccan traditional music. It is distinctive for its rhythmic repetitiveness, its almost arrhythmic swing, and a relentless conversation between the main vocalist and the rest of the musicians, making it deservedly recognized for its capacity to stimulate the listener and induce him/her to a state of trance, along with the performers. The guembri is the only instrument in the Gnawa genre that has a low harmonic range, and it is frequently and correctly compared to a bass guitar by western ears.

Maalem Mahmoud Gania was one of Morocco's most famous Gnawa musicians (1951- 2015 Essaouira). Mahmoud Gania, who belonged to an artistic family that traces its ancestry back to Mali, played a major role in developing Gnawa music in Morocco. He was a respected singer and guembri player and he recorded for both domestic and foreign labels, and collaborated with numerous musicians (e.g. Santana).

With significant tourism and artistic exchanges between Morocco and the West, Gnawa music became internationalized thanks to influences outside the Maghreb, such as Youssou 'n Dour, Wayne Shorter and Randy Weston, who often call upon Gnawa musicians in their compositions. Since 1992, the Gnawa of Morocco have seen their status change, with the creation of the Gnaoua & World Music Festival, boosting their recognition on the international scene.

An example of a Gnawa musician in the new tradition is Abdelmajid Bekkas.

Majid Bekkas is a multi-instrumentalist, singer and composer, born and still living in Sale, Morocco. He learnt Gnawa music through the teachings

of the master/ maâllem Ba Houmane. For many years, Majid Bekkas worked on crossovers with big names in world music and jazz.

Here you find him singing a more traditional Gnawa song about a leader of the Bambara:

Gnawa was inscribed on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity of UNESCO in 2019. ich.unesco.org/en/RL/gnawa-01170

(Picture of Majid Bekkas- Rabat)

(Picture of Majid Bekkas- Rabat)

III. Chaabi music

Popular Moroccan music is called chaabi (folk) music. It is commonly played at modern weddings or on commercial radio channels.

One special artist in this style is Najat Aatabou, who wrote her own chaabi music starting in the 70s. She was a feminist, not focussed on singing beautifully or technically correctly like the classical divas from the Middle East, but instead emphasizing lyrics and but emotions. She was originally from the Middle Atlas. When she reached the age of thirteen, she would sneak out of her bedroom window and sing at local weddings and school parties. After being threatened by her family, she moved to Casablanca upon invitation of a music producer who discovered her singing. Her biggest hit in the Arabic world and the South of Europe, Hadi Kedba Bayna (Just tell me the truth - 1992), was about a woman whose husband is cheating on her. The song was later on sampled by the Chemical Brothers in their 2004 song Galvanize.

One special artist in this style is Najat Aatabou, who wrote her own chaabi music starting in the 70s. She was a feminist, not focussed on singing beautifully or technically correctly like the classical divas from the Middle East, but instead emphasizing lyrics and but emotions. She was originally from the Middle Atlas. When she reached the age of thirteen, she would sneak out of her bedroom window and sing at local weddings and school parties. After being threatened by her family, she moved to Casablanca upon invitation of a music producer who discovered her singing. Her biggest hit in the Arabic world and the South of Europe, Hadi Kedba Bayna (Just tell me the truth - 1992), was about a woman whose husband is cheating on her. The song was later on sampled by the Chemical Brothers in their 2004 song Galvanize.

IV. Chleuh music

This is a music style sung in Amazigh (Berber) dialect, often used in Ahwach ceremonies, collective celebrations by men and women performing in singing and dancing. Tiznit is the home of the Conservatory of Lhaj Belaïd, named after an important figure in this music style. He was a poet and ribab (African violin) player and a troubadour born in the 19th century. He was the first nationally renowned Chleuh (Soussi Berber musician) and also the first to have a record label in Paris.

Ajddig: The flower

Amazigh music relies on its lyrics, which deal with all aspects of life, and also on its rhythms, which move the listener and push him/her to interact with it, even if he/she does not understand the meaning of the words. His timeless refrains have been reprised, since the thirties, by subsequent generations.

Nowadays artists like Ribab Fusion return to this tradition with a modern variation:

V. Sahara Blues

Morocco has its own desert blues, the style famous desert blues bands like Tinariwen, Bombino and Tamikrest share, but while their lyrics are in Tamasheq, the language of the Tuareg, they sing in Hassaniya dialect. Hassaniya Arabic is a mix of classical and dialect Arabic and has its origin in Bedouin dialect.

A popular young group in this genre is Generation Taragalte, who come from Mhamid El Ghizlane, the last oasis before the Sahara of Morocco. They are linked to the Taragalte festival, a three-day musical celebration of nomad culture in the Sahara.

A popular young group in this genre is Generation Taragalte, who come from Mhamid El Ghizlane, the last oasis before the Sahara of Morocco. They are linked to the Taragalte festival, a three-day musical celebration of nomad culture in the Sahara.

Their great example, however, is Tinariwen, the legendary Tuareg group from the Sahara in northern Mali, who wrote their last (ninth) album in their region and recorded their video there:

(Tenere Sastanaqam: "Tenere, tell me if there is anything more beautiful than traveling with your friends and a waterproof goat skin and knowing where to find water even in the most unlikely places.")

Tinariwen are icons of freedom and resistance among the nomadic Tuareg of the Sahara and beyond. The word tinariwen is the plural of ténéré, which simply means “desert” in Tamasheq. They write songs describing the pain of exile, the longing for lost homes and families, the struggle for political and cultural freedom, and the rigors of everyday life in the desert. Their music became the soundtrack for a whole generation of exiled Touareg youth who were living a hand-to-mouth existence in exile in Algeria and Libya. Bandleader Ibrahim Ag Alhab transposed the traditional melodies of the Touareg for the electric guitar, mixing them with blues, rock, pop, Berber, and Arabic influences, thus creating a modern desert rock sound, whose harsh simplicity was well-suited to the realities of their people.

Tinariwen are icons of freedom and resistance among the nomadic Tuareg of the Sahara and beyond. The word tinariwen is the plural of ténéré, which simply means “desert” in Tamasheq. They write songs describing the pain of exile, the longing for lost homes and families, the struggle for political and cultural freedom, and the rigors of everyday life in the desert. Their music became the soundtrack for a whole generation of exiled Touareg youth who were living a hand-to-mouth existence in exile in Algeria and Libya. Bandleader Ibrahim Ag Alhab transposed the traditional melodies of the Touareg for the electric guitar, mixing them with blues, rock, pop, Berber, and Arabic influences, thus creating a modern desert rock sound, whose harsh simplicity was well-suited to the realities of their people.

The way the people of the Sahara are connected to their region is reflected in the song Hasna ya leila, in Hassaniya dialect, which is played all across the borders of the Sahel.

By Generation Taragalte

We find the same structure in music from Mali; Ali Farka Touré's compositions are a good example.

VI. Nass el ghiwane - Rebellion

Everyone who wants to master the Moroccan repertoire must know Nass el Ghiwane.

They are a Moroccan group from Casablanca that first appeared during the late 1960s. Film director Martin Scorsese once referred to them as The Rolling Stones of Africa.

At a time where the only music available was middle-eastern pop music about love, Nass el Ghiwane had something new for Morocco: they used authentic Moroccan instruments and mixed Sufi chants of Zaouias (brotherhoods) like the Hmadcha and Aissawa with the colloquial poetry of Melhoun, adding to it the ancient rhythms of the Amazigh and the trance dance of the Gnawa.

They are a Moroccan group from Casablanca that first appeared during the late 1960s. Film director Martin Scorsese once referred to them as The Rolling Stones of Africa.

At a time where the only music available was middle-eastern pop music about love, Nass el Ghiwane had something new for Morocco: they used authentic Moroccan instruments and mixed Sufi chants of Zaouias (brotherhoods) like the Hmadcha and Aissawa with the colloquial poetry of Melhoun, adding to it the ancient rhythms of the Amazigh and the trance dance of the Gnawa.

They were the first Moroccan band to mix such a diverse and rich heritage and to speak there about the most forbidden subjects, which could have led to imprisonment in the troubled and autocratic Morocco of the 70s, with no freedom of speech.

Nass el Ghiwane specialized in writing poetic lyrics (mostly to avoid censorship) about the social and political climate, and in arranging their music in the Moroccan tradition.

They were the voice of the youth and oppressed class and on several occasions they were banned from selling their records and playing live venues because of the incredible amount of freedom and energy they delivered to their public.

Nass el Ghiwane specialized in writing poetic lyrics (mostly to avoid censorship) about the social and political climate, and in arranging their music in the Moroccan tradition.

They were the voice of the youth and oppressed class and on several occasions they were banned from selling their records and playing live venues because of the incredible amount of freedom and energy they delivered to their public.

VII. Mystical trance - Women of Sufism

The Gnawa ceremonies, lila, share their functions with the hadra ceremonies of other Moroccan Sufi and Sufi-inspired groups such as the Issawa, Hamadcha and Jilala.

Issawa and Hamdouchia, crucial Sufi brotherhoods in Morocco, are known for their bewitching dances and music that entangle their practitioners in a healing trance.

All groups use music, song, and dance to enable communication with the spirits. All of the groups sing invocations to God, the Prophet Muhammad, and various Muslim saints of the Middle East and Morocco in order to purify their intentions in the performance of the ritual. Most Moroccan brotherhoods trace their spiritual authority back to a founding saint. They begin their ceremonies by reciting that saint's written works or spiritual prescriptions in Arabic. In this way, they are given the authority to perform the ceremony. The Gnawa, whose ancestors were neither literate nor Arabic speakers, begin the lila by remembering, through song and dance, the Gnawa of times past, their saints and lands of origin, the experiences of their slave ancestors, and their tales of separation and loneliness, and ultimately redemption.

The different spiritual music genres are also represented by groups of women from Essaouira, the Haddarates. Their singing and rhythmic mystical performance is done with percussion like tarija, Darbuka and metal trays, and they lead collective trance ceremonies at home (hadra), strictly for women. Their ancestors practiced a kind of religious syncretism by realizing the junction between the lila of the Gnawa and the hadhra of the Aïssawa.

Issawa and Hamdouchia, crucial Sufi brotherhoods in Morocco, are known for their bewitching dances and music that entangle their practitioners in a healing trance.

All groups use music, song, and dance to enable communication with the spirits. All of the groups sing invocations to God, the Prophet Muhammad, and various Muslim saints of the Middle East and Morocco in order to purify their intentions in the performance of the ritual. Most Moroccan brotherhoods trace their spiritual authority back to a founding saint. They begin their ceremonies by reciting that saint's written works or spiritual prescriptions in Arabic. In this way, they are given the authority to perform the ceremony. The Gnawa, whose ancestors were neither literate nor Arabic speakers, begin the lila by remembering, through song and dance, the Gnawa of times past, their saints and lands of origin, the experiences of their slave ancestors, and their tales of separation and loneliness, and ultimately redemption.

The different spiritual music genres are also represented by groups of women from Essaouira, the Haddarates. Their singing and rhythmic mystical performance is done with percussion like tarija, Darbuka and metal trays, and they lead collective trance ceremonies at home (hadra), strictly for women. Their ancestors practiced a kind of religious syncretism by realizing the junction between the lila of the Gnawa and the hadhra of the Aïssawa.

For the last few years, they have also performed at public events and music festivals where their powerful playing blows the audience away.

VIII. Fusion

VIII. Fusion

Aziz Sahmaoui is one of Morocco's greatest fusion musicians, who performed several times at the Bimhuis in Amsterdam, and also at the Taragalte festival in Morocco's Sahara. He was born in Marrakech and grew up with Gnawa music. Later he moved to Paris, where he became a founder of the rousing Orchestre National de Barbès, who mix reggae and chanson with North African influences

For his latest band, University of Gnawa, he dove deep into the Gnawa, Hamdouchia, Chaabi and also western styles for his compositions.

For his latest band, University of Gnawa, he dove deep into the Gnawa, Hamdouchia, Chaabi and also western styles for his compositions.

…Finally, based on all this inspiration, Samira's Blues was born two years ago. We play spiritual traditionals and originals with African, Amazigh and Arabic roots.

Together with guitarist Bas Gaakeer we recorded a little video of a Sahel song in Hassaniya dialect, which was also performed by Tinariwen in the 80s, and it went viral among the Tuareg. We recorded our first EP, Ya Baba, which is a tribute to my father but also to the Father, God.

Together with guitarist Bas Gaakeer we recorded a little video of a Sahel song in Hassaniya dialect, which was also performed by Tinariwen in the 80s, and it went viral among the Tuareg. We recorded our first EP, Ya Baba, which is a tribute to my father but also to the Father, God.

Our new arrangement for a Gnawa piece was also well-received in Morocco and The Netherlands.

Ghoumari

*Every day I think of you

Every night I wait for you

Ghoumari, Ghoumari

Lalla Mimouna

Queen of the Gnawa

Oh fortunates

women and men

Pelgrims of the zaouia

Sidna Bilal

May the ancestors rest in peace

God is everlasting

Glory to god

The Gnaouia

*Every day I think of you

Every night I wait for you

Ghoumari, Ghoumari

Lalla Mimouna

Queen of the Gnawa

Oh fortunates

women and men

Pelgrims of the zaouia

Sidna Bilal

May the ancestors rest in peace

God is everlasting

Glory to god

The Gnaouia

related events

related content

people – 21 dec. 2021

Samira Dainan

refered to from:

podcast Rana Ghavami – 23 jun. 2020