From 'Collective Anonymity' to 'Individual Mark': Rediscovering African Art as a Model for Participatory, Interactive and Environmentalist Education

Essay by Narcisse Santores Tchandeu

essaytopic: My learning is affected by the condition of my life

This essay by Narcisse Santores Tchandeu is based on transversal approaches in art / cultural history, anthropology and sociology of change and investigates how the question of education / learning / artistic training or through art has very often been posed only through the prism of the performance of institutions inherited from the colonial period, as if ancient African societies were foreign to it. Tchandeu describes the undoubtedly disconnection between the current system of art and the public, which makes art as a "whites thing'' and how this idea is increasingly attached to the social life of this activity. Rediscovering African art as an inclusive, interactive and environmentalist activity, as promoted in pre-colonial societies, opens up some interesting avenues for reflection in the scrutiny of alternative forms of collective education for local audiences.

From "Collective Anonymity" to "Individual Mark": Rediscovering African Art as a Model for Participatory, Interactive and Environmentalist Education was commissioned for the project My learning is affected by the condition of my life, a symposium spread over time by Aude Christel Mgba, which is an experiment of various forms of learning, listening, touching, transmitting and producing knowledge. The essay is translated in English from French by Edwin Nasr.

From "Collective Anonymity" to "Individual Mark": Rediscovering African Art as a Model for Participatory, Interactive and Environmentalist Education was commissioned for the project My learning is affected by the condition of my life, a symposium spread over time by Aude Christel Mgba, which is an experiment of various forms of learning, listening, touching, transmitting and producing knowledge. The essay is translated in English from French by Edwin Nasr.

From 'Collective Anonymity' to 'Individual Mark': Rediscovering African Art as a Model for Participatory, Interactive and Environmentalist Education

By Narcisse Santores Tchandeu

Translated from French by Edwin Nasr[/h1]

Keywords: African art, education / learning / training, pre and postcolonial models.

Author’s Biography:

Narcisse Santores Tchandeu holds a PhD in Art History. He is a lecturer and researcher at the University of Yaoundé I. His expertise lies in various inventory projects initiated around Cameroon’s local and national cultural heritage. Tchandeu is a member of the Society of Africanist Archaeologists (SAFA) and was selected in 2019 as a postdoctoral researcher at the National Institute for Art History (INHA) in Paris, France.

Abstract

The question of artistic or arts-based education, learning, and training has all too often only been posed and concerned with the performance of institutions inherited from the colonial period, as if ancient African societies were foreign to it. This undoubtedly justifies a certain disconnection between the current art system and the public, to a point where the idea of art as an activity strictly practiced by 'white people' has increasingly become attached to its social life. Rediscovering African art as an inclusive, interactive and environmentalist activity, as promoted in pre-colonial societies, opens up some interesting avenues for one to reflect on, particularly when thinking of alternative forms of collective education for local audiences. The economics of this reflection is based on transversal approaches in art, cultural history, anthropology, and the sociology of social change.

Introduction:

Educated to believe it has "no writing", "no history", "no religion", "no philosophical thought", "no aesthetics", and "no social structure”, Black Africa got off to a bad start, in that it only envisioned its cultural development model on the basis of educational, learning, and training programs inherited from its colonial past. In fact, in schools, institutes or academies of fine arts, architecture, fashion, and crafts, proposed courses still participate today in the exaltation of the knowledge and appropriation of Western art history—from ancient Greece and the Renaissance period to modern and contemporary art—despite that being out of phase with the identity-based realities of the majority of learners. However, the anthropology of ancient African societies reveal both the occurrence of a systematization of the processes of transmission of artistic know-how as well as of arts-based educational initiatives. By questioning the creative relationships between the notions of collectivism and individualism, anonymity and individual mark, inclusive and exclusive facts,

and timeless and temporal acts, this study contributes to a critical reflection on the mutation of paradigms related to art education past and present in Africa.

1. The Dynamism of Pre-Colonial Systems of Artistic Institutionalization, Learning, and Training - The Experience of Shü-mom: Collaborative Writing and Exceptional Learning in Africa:

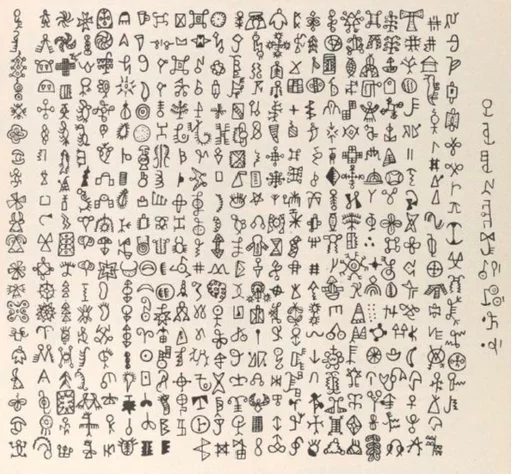

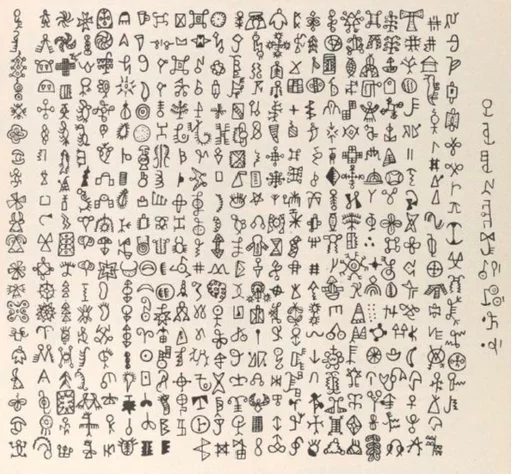

No example can better illustrate the concept of participatory or collaborative art than the process of inventing the Shü-mom script of the Bamun people in northwestern Cameroon, one of the few syllabic alphabet systems attested in Black Africa. The protocol for its creation is said to have been transmitted to Sultan Ibrahim Njoya by a sage in a dream (1st act of collaboration). As soon as he awakened from the dream, and after attempting to have it interpreted by soothsayers in the court, the sultan implemented the protocol of his vision (2nd act of collaboration).

Translated from French by Edwin Nasr[/h1]

Keywords: African art, education / learning / training, pre and postcolonial models.

Author’s Biography:

Narcisse Santores Tchandeu holds a PhD in Art History. He is a lecturer and researcher at the University of Yaoundé I. His expertise lies in various inventory projects initiated around Cameroon’s local and national cultural heritage. Tchandeu is a member of the Society of Africanist Archaeologists (SAFA) and was selected in 2019 as a postdoctoral researcher at the National Institute for Art History (INHA) in Paris, France.

Abstract

The question of artistic or arts-based education, learning, and training has all too often only been posed and concerned with the performance of institutions inherited from the colonial period, as if ancient African societies were foreign to it. This undoubtedly justifies a certain disconnection between the current art system and the public, to a point where the idea of art as an activity strictly practiced by 'white people' has increasingly become attached to its social life. Rediscovering African art as an inclusive, interactive and environmentalist activity, as promoted in pre-colonial societies, opens up some interesting avenues for one to reflect on, particularly when thinking of alternative forms of collective education for local audiences. The economics of this reflection is based on transversal approaches in art, cultural history, anthropology, and the sociology of social change.

Introduction:

Educated to believe it has "no writing", "no history", "no religion", "no philosophical thought", "no aesthetics", and "no social structure”, Black Africa got off to a bad start, in that it only envisioned its cultural development model on the basis of educational, learning, and training programs inherited from its colonial past. In fact, in schools, institutes or academies of fine arts, architecture, fashion, and crafts, proposed courses still participate today in the exaltation of the knowledge and appropriation of Western art history—from ancient Greece and the Renaissance period to modern and contemporary art—despite that being out of phase with the identity-based realities of the majority of learners. However, the anthropology of ancient African societies reveal both the occurrence of a systematization of the processes of transmission of artistic know-how as well as of arts-based educational initiatives. By questioning the creative relationships between the notions of collectivism and individualism, anonymity and individual mark, inclusive and exclusive facts,

and timeless and temporal acts, this study contributes to a critical reflection on the mutation of paradigms related to art education past and present in Africa.

1. The Dynamism of Pre-Colonial Systems of Artistic Institutionalization, Learning, and Training - The Experience of Shü-mom: Collaborative Writing and Exceptional Learning in Africa:

No example can better illustrate the concept of participatory or collaborative art than the process of inventing the Shü-mom script of the Bamun people in northwestern Cameroon, one of the few syllabic alphabet systems attested in Black Africa. The protocol for its creation is said to have been transmitted to Sultan Ibrahim Njoya by a sage in a dream (1st act of collaboration). As soon as he awakened from the dream, and after attempting to have it interpreted by soothsayers in the court, the sultan implemented the protocol of his vision (2nd act of collaboration).

The first concrete step was to involve in the project the two most intelligent dignitaries of the court, Nji Mama and Adjia Nji (3rd act of collaboration); then, to mobilize the whole community by spreading the following prescription: "If you draw a lot of different things and name them, I will make a book that will speak without it being heard" (4th act of collaboration). Around 1895, the king had already gathered 511 characters affected by their pronunciation (phonogram). This embryonic form of the so-called lewa alphabet (fig. 1) would subsequently undergo various transformations. While certain characters were deleted, others were modified and simplified in order to arrive at current ideograms known as aka-uku, based on the influence of Arabic writing, according to certain authors (J. Dugast & M.D.W. Jeffreys, 1950; C. Tardit, 1980). By setting up this perfectible system of composite signs, Njoya engineered the handwritten archiving of his community’s history, but also of administrative and matrimonial acts, cartography, pharmacopoeia documentation, and techniques and technologies (printing, dyeing, weaving, crafts, architecture). By systematizing the use of this writing around 1915 in some fifty schools across Bamum—including for the targeted training of certain princes of neighboring Bamileke chiefdoms (E. Matateyou, 2015)—he laid the first real foundations for an endogenous model of formal education in Africa. Though the French colonial administration banned this form of teaching on the suspicion of it conveying secret codes that advocate for sedition, it was rehabilitated and experienced a great rebirth in the early 2000s, under the influence of the current sultan, Ibrahim Mbombo Njoya.

- Between Formal and Informal Traditional Institutions:

Is it imperative to get out of the myth of a monolithic African culture in order to understand that the models of artistic transmission could have been as dynamic as they are dependent on the complexity of centralized, caste-based, or segmental social organization systems? In court societies, for example, there is solid documentation of the existence of artistic corporations framed by a guild system which participates in the rigorous transmission of know-how. Whether it’s through the prestigious corporations of Iguneromwo bronze or Igbesamwan ivory sculptors in Benin, the famous wood sculptors and ennobled pearl-makers of the royal courts of Grassland-Cameroon, the velvet weavers of Kasai in the Kuba Kingdom, or even the marginalized blacksmiths and sculptors operating within caste-based societies (such as Mandé societies, for example), professional artists in specific fields of specialization have long been promoted. In these cases too, the modernity of Sultan Njoya had consisted in promoting the first museums of living cultures and of a craft village, bringing together, in a stimulating way, different bodies of arts and crafts on the same site.

By way of differentiation from centralized societies, those of the segmental type promoted artists with more independent profiles, who gladly enjoyed an intermittent status which had integrated a perfect daily division of labor between rural activities, hunting, fishing, wine extraction, creation and cultural feasts. It was also in these societies that the training of the artist would undergo the freest form of popular criticism as well as critical interference from clients during the execution of the work, going as far as purchase refusals, such as among the Tiv people of Nigeria (F. Willet, 1990). One must believe that such a democratization of popular criticism in non-centralized societies ended up fostering the development of some of the most spontaneous and fanciful styles on the continent. It is also important to note that it is in this social model, marked by strong initiation institutions, just as in nomadic-type communities, that the rites of promotion among younger age groups often give rise to the remarkable development of popular art. These practices were very often ephemeral and executed without particular expertise; some models, which are still very much alive, proceeded from an intersubjective execution of body paintings, as evidenced by the famous “stick fighting” (donga) rites of the Surma people (fig. 2) or the “parade of the fiancé’s” (gerewol) rites of the Bororo people.

Is it imperative to get out of the myth of a monolithic African culture in order to understand that the models of artistic transmission could have been as dynamic as they are dependent on the complexity of centralized, caste-based, or segmental social organization systems? In court societies, for example, there is solid documentation of the existence of artistic corporations framed by a guild system which participates in the rigorous transmission of know-how. Whether it’s through the prestigious corporations of Iguneromwo bronze or Igbesamwan ivory sculptors in Benin, the famous wood sculptors and ennobled pearl-makers of the royal courts of Grassland-Cameroon, the velvet weavers of Kasai in the Kuba Kingdom, or even the marginalized blacksmiths and sculptors operating within caste-based societies (such as Mandé societies, for example), professional artists in specific fields of specialization have long been promoted. In these cases too, the modernity of Sultan Njoya had consisted in promoting the first museums of living cultures and of a craft village, bringing together, in a stimulating way, different bodies of arts and crafts on the same site.

By way of differentiation from centralized societies, those of the segmental type promoted artists with more independent profiles, who gladly enjoyed an intermittent status which had integrated a perfect daily division of labor between rural activities, hunting, fishing, wine extraction, creation and cultural feasts. It was also in these societies that the training of the artist would undergo the freest form of popular criticism as well as critical interference from clients during the execution of the work, going as far as purchase refusals, such as among the Tiv people of Nigeria (F. Willet, 1990). One must believe that such a democratization of popular criticism in non-centralized societies ended up fostering the development of some of the most spontaneous and fanciful styles on the continent. It is also important to note that it is in this social model, marked by strong initiation institutions, just as in nomadic-type communities, that the rites of promotion among younger age groups often give rise to the remarkable development of popular art. These practices were very often ephemeral and executed without particular expertise; some models, which are still very much alive, proceeded from an intersubjective execution of body paintings, as evidenced by the famous “stick fighting” (donga) rites of the Surma people (fig. 2) or the “parade of the fiancé’s” (gerewol) rites of the Bororo people.

- Between Training, Division of Labor, and "Total Art":

Far from being a “community art” from which the artist is made unconscious of his act, creation in Africa must rather be perceived as a collaborative, participative, or commutative action, wherein the artist is instead fully aware that his gesture participates in different levels of sensitivity, know-how, specialization, temporal as well as timeless interventions. When taking into consideration the conditions of creation of a sculpture, it appears that the framework of training, expertise, specialization, and professionalization all highlight a remarkable division of labor. But in general, the apprentice's training varies according to the type of course or independent workshop, accession by inheritance or co-option (with impact on learning time), quality of the technical platform etc. In the well documented example of wood sculpture, the classic bases of learning ranged from initiation into the symbolic universe of the group, to knowledge of the properties of consecrated plant essences, mastery of tools and their rigorous order of use, observation of the technical gestures of the master, as well as ritual prohibitions (often food and sex-related) of a certain discretionary reserve. In Nigeria, where the most important biographical studies of artist generations have been carried out under the influence of Kenneth Murray’s pioneering work in the 1930s, two main practical steps can sum up the training of the apprentice:

Apprentices also graduate with a strong grasp on technical skills, the expertise level of which varies according to specific objects: first, small utility furniture, for which technical shortcomings are tolerated; then, sacred objects, and in particular large statues and masks, for which no error is admitted. In the latter case, to explain the phenomenon of the artist's deliberate anonymity in favor of an individuation, or even a nominal personification, of the spirit embodied by the mask, Frank Willet points out that: "Among the Montol, the name of the sculptor is kept secret as long as his masks are in use, though it can be revealed afterwards" (1990).

The illustrative case of the Montol of Nigeria clearly reveals the phenomenal perception of artistic activity, conceived as an interweaving of geniuses: the agency of the tree (from which the raw material comes), the creativity of the artist, and the propitiatory quality of the work itself, all of which participate in the temporal and timeless existence of creation. To this, we must add that several trades can intervene in the realization of a single sculpture, which further complicates the concept of authorism. Notions of unfinishedness and completeness also take on their full meaning when a sculptor can deliberately outline the main guidelines of the work, leaving it to be completed, for example, by a specialist in pearl coating in the Grasslands of Cameroon, or by a ritual specialist that encrusts mirrors, nails or fetish bags among the Bavili people of Bas-Congo. The question of attribution is even more perplexed among the Tiv people where, in addition to the fact that the same word gba designates “both divine creation and artistic creation”, according to Willet, “it could happen that four sculptors work in succession on a cane or a stool […], the only criterion being the final outcome.”

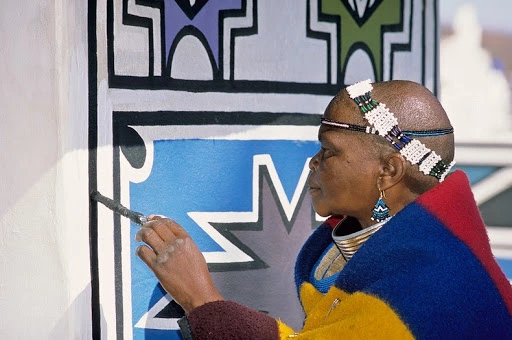

If sculpture is generally presented as a male activity, a significant part of creative processes has nevertheless stemmed from the genius of women, although that fact is very often forgotten in art history manuals of the macho tradition. Women have occupied a privileged place in the development of applied and popular arts in Africa, expressing themselves in fields as varied as pottery, gourd pyrography, basketry (spinning and weaving), bead stringing, as well as wall decoration and body arts (hair styling, scarification, tattoo art, and body painting). Among the most resilient schools in applied arts, which generally consist in transmitting techniques from mother to daughter, we must of course count: potters and midwives; blacksmiths’ wives in caste-based societies, such as Mandé societies; calabash pyrographers and Fulani tattooists; Kikuyu, Turkana, Maasai, and Surma painters and body scarifiers; Himba ‘cosmeticians’ who work around body, skin, and hairdressing protection care (skin and hairdressing); Ndébélé wall decoration painters (fig. 3); and raffia weavers among the Bamun people. Faced with this remarkable conservation of certain cultural traditions, would it not be interesting to apply the concept of “living human treasures”, promoted by UNESCO, so that the custodians of this know-how can pass it on to applied arts and crafts schools across Africa? This concern is all the more relevant as the gradual disappearance of these centuries-old artisanal processes seems to correspond to a period of pressure from the ceramic, textile and make-up industries exported from the West and Asia.

Besides providing a framework for inclusive, collaborative, and participatory forms of artmaking, one of the capital lessons given by African art in the field of universal aesthetics lies in the former’s omnipresence in all types of daily life objects. This can be traced from the most insignificant abbia miniature game token of the Beti people, to the anuan door locks of the Dogon people, Zandé throwing knives, and Baluba headrests, to the masks and sacred statues of sedentary populations. To this omnipresence of art in everyday human activities, we must add an environmental dimension, inviting certain expressions such as megalithism, “sacred groves”, and cult altars—for example, the famous temples of the Voodoo-Fon, Yoruba, Ewe,, Mitsogo, Fang, and binu na-Dogon peoples—participate until today in the sustainable preservation of eco-systemic balances. The representational combination of the spatial and temporal is best evidenced in interactions between the visual and the oratory and scenic arts, granting African creations the true definition of a "total art". In fact, a mask will remain a dead wooden object when displayed in museum contexts, so long as it is disconnected from its wearer, the costume, the verb, the dance, and even from the space, time, and precise audience for which it was designed.

Far from being a “community art” from which the artist is made unconscious of his act, creation in Africa must rather be perceived as a collaborative, participative, or commutative action, wherein the artist is instead fully aware that his gesture participates in different levels of sensitivity, know-how, specialization, temporal as well as timeless interventions. When taking into consideration the conditions of creation of a sculpture, it appears that the framework of training, expertise, specialization, and professionalization all highlight a remarkable division of labor. But in general, the apprentice's training varies according to the type of course or independent workshop, accession by inheritance or co-option (with impact on learning time), quality of the technical platform etc. In the well documented example of wood sculpture, the classic bases of learning ranged from initiation into the symbolic universe of the group, to knowledge of the properties of consecrated plant essences, mastery of tools and their rigorous order of use, observation of the technical gestures of the master, as well as ritual prohibitions (often food and sex-related) of a certain discretionary reserve. In Nigeria, where the most important biographical studies of artist generations have been carried out under the influence of Kenneth Murray’s pioneering work in the 1930s, two main practical steps can sum up the training of the apprentice:

A mechanical phase where the apprentice first becomes familiar with the material through polishing when in the process of finishing the work, followed by direct carving under the coordination of the master, which includes the perfunctory tripartite roughing (head, body, and legs), the precision of the anatomical proportions and, finally, the inscription of details pertaining to direction and decoration;

An analog phase where the apprentice, already experienced in mastering the different stages of creation, knows how to keep the image of the model present in mind in order to reproduce it by himself, from start to finish.

Apprentices also graduate with a strong grasp on technical skills, the expertise level of which varies according to specific objects: first, small utility furniture, for which technical shortcomings are tolerated; then, sacred objects, and in particular large statues and masks, for which no error is admitted. In the latter case, to explain the phenomenon of the artist's deliberate anonymity in favor of an individuation, or even a nominal personification, of the spirit embodied by the mask, Frank Willet points out that: "Among the Montol, the name of the sculptor is kept secret as long as his masks are in use, though it can be revealed afterwards" (1990).

The illustrative case of the Montol of Nigeria clearly reveals the phenomenal perception of artistic activity, conceived as an interweaving of geniuses: the agency of the tree (from which the raw material comes), the creativity of the artist, and the propitiatory quality of the work itself, all of which participate in the temporal and timeless existence of creation. To this, we must add that several trades can intervene in the realization of a single sculpture, which further complicates the concept of authorism. Notions of unfinishedness and completeness also take on their full meaning when a sculptor can deliberately outline the main guidelines of the work, leaving it to be completed, for example, by a specialist in pearl coating in the Grasslands of Cameroon, or by a ritual specialist that encrusts mirrors, nails or fetish bags among the Bavili people of Bas-Congo. The question of attribution is even more perplexed among the Tiv people where, in addition to the fact that the same word gba designates “both divine creation and artistic creation”, according to Willet, “it could happen that four sculptors work in succession on a cane or a stool […], the only criterion being the final outcome.”

If sculpture is generally presented as a male activity, a significant part of creative processes has nevertheless stemmed from the genius of women, although that fact is very often forgotten in art history manuals of the macho tradition. Women have occupied a privileged place in the development of applied and popular arts in Africa, expressing themselves in fields as varied as pottery, gourd pyrography, basketry (spinning and weaving), bead stringing, as well as wall decoration and body arts (hair styling, scarification, tattoo art, and body painting). Among the most resilient schools in applied arts, which generally consist in transmitting techniques from mother to daughter, we must of course count: potters and midwives; blacksmiths’ wives in caste-based societies, such as Mandé societies; calabash pyrographers and Fulani tattooists; Kikuyu, Turkana, Maasai, and Surma painters and body scarifiers; Himba ‘cosmeticians’ who work around body, skin, and hairdressing protection care (skin and hairdressing); Ndébélé wall decoration painters (fig. 3); and raffia weavers among the Bamun people. Faced with this remarkable conservation of certain cultural traditions, would it not be interesting to apply the concept of “living human treasures”, promoted by UNESCO, so that the custodians of this know-how can pass it on to applied arts and crafts schools across Africa? This concern is all the more relevant as the gradual disappearance of these centuries-old artisanal processes seems to correspond to a period of pressure from the ceramic, textile and make-up industries exported from the West and Asia.

Besides providing a framework for inclusive, collaborative, and participatory forms of artmaking, one of the capital lessons given by African art in the field of universal aesthetics lies in the former’s omnipresence in all types of daily life objects. This can be traced from the most insignificant abbia miniature game token of the Beti people, to the anuan door locks of the Dogon people, Zandé throwing knives, and Baluba headrests, to the masks and sacred statues of sedentary populations. To this omnipresence of art in everyday human activities, we must add an environmental dimension, inviting certain expressions such as megalithism, “sacred groves”, and cult altars—for example, the famous temples of the Voodoo-Fon, Yoruba, Ewe,, Mitsogo, Fang, and binu na-Dogon peoples—participate until today in the sustainable preservation of eco-systemic balances. The representational combination of the spatial and temporal is best evidenced in interactions between the visual and the oratory and scenic arts, granting African creations the true definition of a "total art". In fact, a mask will remain a dead wooden object when displayed in museum contexts, so long as it is disconnected from its wearer, the costume, the verb, the dance, and even from the space, time, and precise audience for which it was designed.

2. Identity Construction in the Context of Colonial and Globalized Systems of Artistic Education and Training

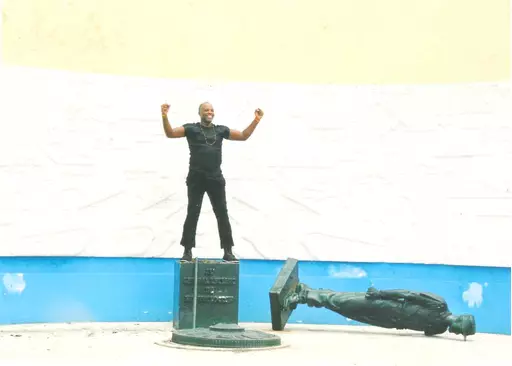

In order to settle permanently in the consciousness of the dominated, colonial powers built monuments all over the continent, baptized streets, cities and countries, and oriented emblems, coats of arms, hymns and school programs, in apology to their own civilization, their heroes, and their "God". Isidor Pascal Njock Nyobé evokes the formula of an "imposed memory, from the memory of elsewhere" (2019), as if to mean "the construction of monuments and urban toponymies that are strongly grateful to the colonizer.” The term recognition might sound like a euphemism if one holds on to Achille Mbembé’s theory of "Necropolitics" (2006). According to the author, far from being initially programmed for the beautification of African cities, colonial statues and monuments "were the sculptural extension of a form of racial terror", the role of which was to “resurrect the dead, who, during their lives, tormented African existences, often with a double-edged sword.” We then understand why, following independence, some African countries undertook the process of renaming themselves as well as various toponyms: The Gold Coast became Ghana, Rhodesia became Zimbabwe, Upper Volta became Burkina Faso, etc. They also inaugurated commemorative statues depicting fathers of the nation. And wherever this counter-acculturation effort had not been made, we could witness a rise in nationalist movements, demanding the destruction of monuments in connection with the distressing past of colonization. Perhaps the most publicized example is the Rhodes Must Fall movement, a student protest initiative born in March 2015 at the University of Cape Town. The movement’s plan to overthrow the bronze statue of Cecil Rhodes, who had served as the Prime Minister of the Cape Colony from 1890 to 1896 and is known as the father of segregationist Rhodesia, quickly became a social symbol of the fight against racial discrimination. A comparable outburst of protest was also

witnessed in Cameroon, where activist André Joël Essama has been imprisoned many times for having vandalized the statue of French General Leclerc and that of the "unknown soldier" in Douala (fig 4). The activist also claims having debunked about 50 nameplates of toponyms that are apologetic of French colonial surnames.

The Stigmata of Identity Alienation: Colonial Monuments and Looted Objects:

In order to settle permanently in the consciousness of the dominated, colonial powers built monuments all over the continent, baptized streets, cities and countries, and oriented emblems, coats of arms, hymns and school programs, in apology to their own civilization, their heroes, and their "God". Isidor Pascal Njock Nyobé evokes the formula of an "imposed memory, from the memory of elsewhere" (2019), as if to mean "the construction of monuments and urban toponymies that are strongly grateful to the colonizer.” The term recognition might sound like a euphemism if one holds on to Achille Mbembé’s theory of "Necropolitics" (2006). According to the author, far from being initially programmed for the beautification of African cities, colonial statues and monuments "were the sculptural extension of a form of racial terror", the role of which was to “resurrect the dead, who, during their lives, tormented African existences, often with a double-edged sword.” We then understand why, following independence, some African countries undertook the process of renaming themselves as well as various toponyms: The Gold Coast became Ghana, Rhodesia became Zimbabwe, Upper Volta became Burkina Faso, etc. They also inaugurated commemorative statues depicting fathers of the nation. And wherever this counter-acculturation effort had not been made, we could witness a rise in nationalist movements, demanding the destruction of monuments in connection with the distressing past of colonization. Perhaps the most publicized example is the Rhodes Must Fall movement, a student protest initiative born in March 2015 at the University of Cape Town. The movement’s plan to overthrow the bronze statue of Cecil Rhodes, who had served as the Prime Minister of the Cape Colony from 1890 to 1896 and is known as the father of segregationist Rhodesia, quickly became a social symbol of the fight against racial discrimination. A comparable outburst of protest was also

witnessed in Cameroon, where activist André Joël Essama has been imprisoned many times for having vandalized the statue of French General Leclerc and that of the "unknown soldier" in Douala (fig 4). The activist also claims having debunked about 50 nameplates of toponyms that are apologetic of French colonial surnames.

If with regard to the dominated, the colonial monument evokes a particularly painful memory (more when it represents the armed soldier or the administrator proud of his stripes), Judeo-Christian or Islamic religious icons and symbols have nevertheless also participated in an subtle alienation of historical consciousness as well as a radical break with old beliefs. Under the pretext of the civilizing and evangelistic mission of these foreign religions, the African continent, more than any other, has paid the heaviest price for spoliations of all kinds. Within the cultural field, this hcounterpartas resulted not only in the radical prohibition of many religious rituals, but also in a massive deportation of artworks that certain African communities have been completely stripped of. These findings are so alarming that a great deal of young African art researchers who, beyond book catalogs, are made unaware of the continent's heritages, only to discover them for the first time in Western museums. In this regard, I keep in mind the memory of one of my visits in December 2019 to the Musée du Quai Branly, accompanied by an Ivorian student. Impressed by the great diversity African doll models—Ndébélé, Doayo, Fali, Peule, Toucouleur, Mbédik, Vuté, Baguirmi (fig. 5)—the student could not help but be moved by the idea of having only known of the "white doll" in her early childhood. And though Western manufacturers have gradually introduced an alternative "black doll" model on the market, it remains curiously very little preferred to its white counterpart.

A comparable psychological archetype has been the subject of an exhibition1 which features black dolls (fig. 6) dating back to the slave trade period. Faced with these various historical dramas which have deeply destabilized the identity benchmarks of Africans, passions are increasingly crystallizing around restituting heritages that have been looted or unequally acquired during the colonial period.

- Institutional, Formal, and Informal Systems of Education and Training: The Case of Postcolonial Cameroon:

Cameroon is an excellent case in which cultural policies have been built by subjugating arts education for the needs of the unitary cause, cohesion, and national integration. The transformation and transversality of the ministerial departments in charge of art reflects less ambitious planning of long-term cultural policies than a desire for systematic control of socio-cultural content. Following the independence of the Federal Republic of Cameroon, artistic activity was first taken over by the Federal Linguistic and Cultural Center, before being attached to the Directorate of Cultural Affairs at the Ministry of Education, Youth and Culture. The government’s aim was to plant within schools the seeds of a national consciousness enriched by the ethnocultural diversity of the country. This initiative was reinforced by the systematization of the colonial project of "cultural centers", the oldest formal learning institutions. They are organized according to Jean Calvin Bahoken and Engelbert Atangana (1975) as centers of post- and extracurricular activities:1) “… these centers were all at the same time museums, libraries, theaters and conferences, etc. They were found generally close to the regional school and employed members of the teaching staff as animators.” It is also one of these centers, initiated by a teacher in Ebolowa to train workers, apprentices, and students in the trades of wood, forge and basketry, that will be transformed, in 1945, into an official craftsmanship school by French drawer Raymond Lecocq. In favor of the influence of cultural centers and that of artists, mediums or trends in Western modern art, the avant-garde of artistic renewal in Cameroon later asserted itself around two types of training: a professional training whose rooting from the colonial period was symbolized by the major work in painting of pioneers such as Rigoberg Ndjeng, Martin Abessolo, Koko Léa-Mbarga Biloa, Engelberg Mveng, Salomon Momo, Koko Komégné, and Ebénézer Malon; and an academic training in more diversified techniques, such as painting, mosaic, sculpture, and scenography, represented in 1960 by the curriculum of Gaspar Goman in Spain, followed by more experiences in France (Etaba Etaba, Pascal Kenfack, and Réné Tchébétchou), as well as the rather atypical Kouam Tawadjé course in China.

In 1972, artistic activities were dissociated from educational courses by the August 28 Decree No. 72/425, henceforth attaching the Directorate of Cultural Affairs to the Ministry of Information and Culture. In its article 34 of section V, this decree specifies, however, that the Department of Cultural Dissemination and Animation is responsible, among other things, for “popular and school-related education in artistic matters, in particular through the production and dissemination, in conjunction with the Ministry of National Education, of artistic-cultural documents and cultural popularization programs.” It was not until the early 1990s that the socio-political and economic crises led to the holding of the National Forum on Culture in 1991, itself at the origin of the creation of the Ministry of Culture in 1992, which would then become autonomously in charge of artistic activity. In the wake of public authorities’ renewed interest in art, the latter was reinstated in educational programs, following the transformation, in 1993, of several former university-related faculties of literature and human sciences into faculties of art, literature and human sciences. The Fine Arts and History of Art branch of the University of Yaoundé I—a sort of ‘pilot school’ leading that reform—was distinguished by a fairly atypical course in Africa. Its teaching reconciled the practical or professional training of institutes of fine arts, with fundamental research in the history of art that would usually be carried out in university faculties. But, here as elsewhere in Africa, where the theoretical, critical, museographic or heritage-based approaches to art are still very unequal, educational and vocational training systems remained essentially dependent on textbooks, and would mainly be delivered by foreign authors providing Western tools and knowledges. This translates, for example, into a fairly frequent orientation of fine arts dissertations around two axes: an anthropological axis carrying the watered-down, identity-based claim of a certain Africanity; and a conceptual and creative axis mainly subject to a theory, school, current of thought, or stylistic movement specific to the history of Western art.

Laws promoted at the dawn of the 1990s and relating to individual, associative, and communication-related freedoms, galvanized private cultural and educational organizations. It is in this context that the most influential private cultural and educational organization of the Cameroonian art scene were set up, among them: doual'art, the country’s main center of contemporary art, inaugurated in 1991 and host of the Salon Urbain de Douala (SUD), among the most popular urban art triennials on the continent; and The Institut de Formation Artistique (IFA) created in 1992 in Mbalmayo, and which remains the only private secondary art education establishment in the country. Training programs were promoted by Italian missionaries and naturally resembled those of a Western fine arts school, but here too acquired a certain search for African anthropological content as a lure of authenticity. The example of these programs’ fascination for the “soulless'' mask, as one of the most popular motifs among learners, is quite symptomatic of the fantasized expression of an Africanity that is in fact watered down by brushstrokes that claim and echo the classicism of Poussin, the realism of Courbet, the pointillism of Seurat, or the cubism of Picasso. Within the informal training sector, whereas the first artists' associations established throughout the 1970s and 1980s, such as the MADUTA Circle and the UDAPCAM, faced many institutional difficulties, those established in the 1990s, such as Prim'art and Club Kéops, and especially the 2000s, such as Kapsiki Circle and Dreamers, left a more durable mark on the artistic scene. But it is Goddy Leye's 2003-2013 project, Art Bakery, which was linked to the artistic village of Bonendalé, that we must recognize as the most structured informal training initiative in recent decades. Art Bakery has the undoubted merit of having not only promoted creative and discursive residencies for artists, but of promoting and popularizing experimentation with multimedia within the local contemporary landscape.

3. Learning to Rediscover African Art as a Foreshadowing of Modern and Contemporary Art Movements

Following a formal or informal training in art, it is always very intriguing to note the desire for graduating African artists to have the modernity, contemporaneity, or internationalization of their style prevail by claiming they're influenced by artists, art movements, currents of thought, and mediums belonging to the Western art canon. This type of historical irony is particularly fragrant when we are reminded that it is paradoxically the rediscovery of the so-called primitive arts by the avant-garde of modern art that profoundly influenced the artistic revolutions of the twentieth century in the West as well as the rise of photography therein—the latter of which came as a result of questioning the dominance of the naturalist tradition over three millennia. Thus, when Western fine artists, stylists, scenographers, architects, and designers in need of inspiration are increasingly resourcing themselves through the unsuspected heritage of African art, we can also find, rather paradoxically, an opposite movement on account of local creators.

Fortunately, and not unlike Picasso, Braque, Matisse, and Modigliani, some African creators have drawn inspiration from the ancient arts in order to stimulate a renewal of local iconographic traditions. In this sense, Sultan Ibrahim Njoya is perceived as a true avant-garde leader for having modernized, at the beginning of the 20th century, the graphic principles of Bamun writing, adapting them to the illustration of portraits, cartography, and architectural plans. His restitution of the narrative genealogy of the Bamun sultans through symbolic portraits of their personality—which came in the form of vignettes accompanied by anecdotes in Shü-mom script—was considered to be a pioneering work in the field of African comics. Another equally interesting example of a reinvention of traditional styles can be found through the immense oeuvre of Gaspar Goman and his contributions in the fields of painting and public art, though he was, paradoxically, one of the first Cameroonian graduates of Spanish fine arts academies in the 1960s. His revivalist style revival consists of a dynamic reappropriation of the proportions of Fang statues and African multiform masks and decorative motifs, which are then adapted to the rules of pictorial compositions as advanced by Cubism, Neo- and Post-Impressionism. While presenting a methodical academicism, his works are nonetheless endearing in that they articulate a nostalgia for the forms they leave to be discovered, and are sensitive to the monumental mosaics that decorate public and private buildings, from Equatorial Guinea to the People's Republic of the Congo and Cameroon (fig. 7).

Cameroon is an excellent case in which cultural policies have been built by subjugating arts education for the needs of the unitary cause, cohesion, and national integration. The transformation and transversality of the ministerial departments in charge of art reflects less ambitious planning of long-term cultural policies than a desire for systematic control of socio-cultural content. Following the independence of the Federal Republic of Cameroon, artistic activity was first taken over by the Federal Linguistic and Cultural Center, before being attached to the Directorate of Cultural Affairs at the Ministry of Education, Youth and Culture. The government’s aim was to plant within schools the seeds of a national consciousness enriched by the ethnocultural diversity of the country. This initiative was reinforced by the systematization of the colonial project of "cultural centers", the oldest formal learning institutions. They are organized according to Jean Calvin Bahoken and Engelbert Atangana (1975) as centers of post- and extracurricular activities:1) “… these centers were all at the same time museums, libraries, theaters and conferences, etc. They were found generally close to the regional school and employed members of the teaching staff as animators.” It is also one of these centers, initiated by a teacher in Ebolowa to train workers, apprentices, and students in the trades of wood, forge and basketry, that will be transformed, in 1945, into an official craftsmanship school by French drawer Raymond Lecocq. In favor of the influence of cultural centers and that of artists, mediums or trends in Western modern art, the avant-garde of artistic renewal in Cameroon later asserted itself around two types of training: a professional training whose rooting from the colonial period was symbolized by the major work in painting of pioneers such as Rigoberg Ndjeng, Martin Abessolo, Koko Léa-Mbarga Biloa, Engelberg Mveng, Salomon Momo, Koko Komégné, and Ebénézer Malon; and an academic training in more diversified techniques, such as painting, mosaic, sculpture, and scenography, represented in 1960 by the curriculum of Gaspar Goman in Spain, followed by more experiences in France (Etaba Etaba, Pascal Kenfack, and Réné Tchébétchou), as well as the rather atypical Kouam Tawadjé course in China.

In 1972, artistic activities were dissociated from educational courses by the August 28 Decree No. 72/425, henceforth attaching the Directorate of Cultural Affairs to the Ministry of Information and Culture. In its article 34 of section V, this decree specifies, however, that the Department of Cultural Dissemination and Animation is responsible, among other things, for “popular and school-related education in artistic matters, in particular through the production and dissemination, in conjunction with the Ministry of National Education, of artistic-cultural documents and cultural popularization programs.” It was not until the early 1990s that the socio-political and economic crises led to the holding of the National Forum on Culture in 1991, itself at the origin of the creation of the Ministry of Culture in 1992, which would then become autonomously in charge of artistic activity. In the wake of public authorities’ renewed interest in art, the latter was reinstated in educational programs, following the transformation, in 1993, of several former university-related faculties of literature and human sciences into faculties of art, literature and human sciences. The Fine Arts and History of Art branch of the University of Yaoundé I—a sort of ‘pilot school’ leading that reform—was distinguished by a fairly atypical course in Africa. Its teaching reconciled the practical or professional training of institutes of fine arts, with fundamental research in the history of art that would usually be carried out in university faculties. But, here as elsewhere in Africa, where the theoretical, critical, museographic or heritage-based approaches to art are still very unequal, educational and vocational training systems remained essentially dependent on textbooks, and would mainly be delivered by foreign authors providing Western tools and knowledges. This translates, for example, into a fairly frequent orientation of fine arts dissertations around two axes: an anthropological axis carrying the watered-down, identity-based claim of a certain Africanity; and a conceptual and creative axis mainly subject to a theory, school, current of thought, or stylistic movement specific to the history of Western art.

Laws promoted at the dawn of the 1990s and relating to individual, associative, and communication-related freedoms, galvanized private cultural and educational organizations. It is in this context that the most influential private cultural and educational organization of the Cameroonian art scene were set up, among them: doual'art, the country’s main center of contemporary art, inaugurated in 1991 and host of the Salon Urbain de Douala (SUD), among the most popular urban art triennials on the continent; and The Institut de Formation Artistique (IFA) created in 1992 in Mbalmayo, and which remains the only private secondary art education establishment in the country. Training programs were promoted by Italian missionaries and naturally resembled those of a Western fine arts school, but here too acquired a certain search for African anthropological content as a lure of authenticity. The example of these programs’ fascination for the “soulless'' mask, as one of the most popular motifs among learners, is quite symptomatic of the fantasized expression of an Africanity that is in fact watered down by brushstrokes that claim and echo the classicism of Poussin, the realism of Courbet, the pointillism of Seurat, or the cubism of Picasso. Within the informal training sector, whereas the first artists' associations established throughout the 1970s and 1980s, such as the MADUTA Circle and the UDAPCAM, faced many institutional difficulties, those established in the 1990s, such as Prim'art and Club Kéops, and especially the 2000s, such as Kapsiki Circle and Dreamers, left a more durable mark on the artistic scene. But it is Goddy Leye's 2003-2013 project, Art Bakery, which was linked to the artistic village of Bonendalé, that we must recognize as the most structured informal training initiative in recent decades. Art Bakery has the undoubted merit of having not only promoted creative and discursive residencies for artists, but of promoting and popularizing experimentation with multimedia within the local contemporary landscape.

3. Learning to Rediscover African Art as a Foreshadowing of Modern and Contemporary Art Movements

Following a formal or informal training in art, it is always very intriguing to note the desire for graduating African artists to have the modernity, contemporaneity, or internationalization of their style prevail by claiming they're influenced by artists, art movements, currents of thought, and mediums belonging to the Western art canon. This type of historical irony is particularly fragrant when we are reminded that it is paradoxically the rediscovery of the so-called primitive arts by the avant-garde of modern art that profoundly influenced the artistic revolutions of the twentieth century in the West as well as the rise of photography therein—the latter of which came as a result of questioning the dominance of the naturalist tradition over three millennia. Thus, when Western fine artists, stylists, scenographers, architects, and designers in need of inspiration are increasingly resourcing themselves through the unsuspected heritage of African art, we can also find, rather paradoxically, an opposite movement on account of local creators.

Fortunately, and not unlike Picasso, Braque, Matisse, and Modigliani, some African creators have drawn inspiration from the ancient arts in order to stimulate a renewal of local iconographic traditions. In this sense, Sultan Ibrahim Njoya is perceived as a true avant-garde leader for having modernized, at the beginning of the 20th century, the graphic principles of Bamun writing, adapting them to the illustration of portraits, cartography, and architectural plans. His restitution of the narrative genealogy of the Bamun sultans through symbolic portraits of their personality—which came in the form of vignettes accompanied by anecdotes in Shü-mom script—was considered to be a pioneering work in the field of African comics. Another equally interesting example of a reinvention of traditional styles can be found through the immense oeuvre of Gaspar Goman and his contributions in the fields of painting and public art, though he was, paradoxically, one of the first Cameroonian graduates of Spanish fine arts academies in the 1960s. His revivalist style revival consists of a dynamic reappropriation of the proportions of Fang statues and African multiform masks and decorative motifs, which are then adapted to the rules of pictorial compositions as advanced by Cubism, Neo- and Post-Impressionism. While presenting a methodical academicism, his works are nonetheless endearing in that they articulate a nostalgia for the forms they leave to be discovered, and are sensitive to the monumental mosaics that decorate public and private buildings, from Equatorial Guinea to the People's Republic of the Congo and Cameroon (fig. 7).

Two renowned artists illustrate quite well the contrasting methodological approaches in renewing the spirit of African monumental sculpture: Ousman Sow from Senegal and Joseph Francis Sumegné from Cameroon. Sow, who authored famous series such as the Nouba, Masai (fig. 8), Zulu, Fulani, etc. is inspired by epic ethnic groups of African cultures that he represents according to naturalists conventions, tinged with a certain humanism inherited from the Renaissance. His creations are produced through a particular technique of mixed or bronze casting, and celebrate an anthropocentrism exacerbated by the mastery of human anatomy (owing to his training as a physiotherapist) and the expression of emotions and movement—in short, aesthetic counter-values in relation to ideals of transcendence and de-personification found in traditional African statues.

In a completely different register, the lesser-known monumental work of Sumegné addresses the issues specific to the society of his time by way of unearthing the soul of symbolic statues through recycling techniques as well as traditional weaving and beading techniques. His most famous public monument, the Statue of New Liberty in Douala (fig. 9), highlights the universal humanness of a character-symbol that echoes industrial rebus, and is entirely constructed from the assembly of metallic, plastic, and electronic materials. Balanced on one leg, as if performing a classical dance step, the character is holding a globe with his right hand above his head, symbolizing everyone's responsibility for the future of the planet.

As they become more experimented with by a new generation of African creators, other contemporary techniques such as multimedia installation, land art, and performance deserve to be questioned in light of the historical relationships between artists, audiences, and the sensorial perception of space, time, and corporeality. In fact, for the vast majority of artists who discover these processes under the influence of Western funding programs and international mobility, there remains an unspoken code they are expected to follow that disconnects them from space, time, and their own audience. Not all is lost, though. It is indeed also necessary to note artists’ renewed interest in engaging in an educational, sensory, and subversive reappropriation of the corporal, scenographic, environmental, and semiological codes inherited from history, anthropology, and sociology. However, in the fairly illustrative case of performance, for example, the rediscovery of this artistic process within cultural traditions unfortunately leads to confusing its codes with that of the outcome of a simple ritual. This is the posture espoused by the Nigerian promoter of the AFiRIperFOMA biennial, Jelili Atiku, when he declares that, in Africa, “most cultural productions were created for performance… Even traditional ceremonies held during funerals are performances.” In another approach, the concept of “ritual theater”, initiated by Ivorian-Cameroonian scenographer Werewere Liking, also the promoter of the Ki Yi M'Bock group in Abidjan, postulates for a reconstruction of memory in Africa, which consists in remembering certain sacred rites by staging them within an improvisation game. Not far from this approach, Guinean Souleymane Koly, founder of the Kotéba troupe, reframes the Mandeng ritual as a tool to denunciate and overcome the faults of society. In Cameroon, a recent production echoing the topicality of the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic reconciles the creation by the artist Tally Mbok of a synthetic fang-style mask with a performative staging by Christian Etongo(fig 10), providing an intriguing reconsideration of the role of the inquisitive, punitive, and vigilantist mask in a society in need of good citizenship. As edifying as they are, all these approaches are exposed to two kinds of potential drifts: that of the theatrical staging of fictional content in which the space, time, and role-playing of the participants are predefined; and that of the exotic content of a rite representing, as would a work of documentary-fiction, an Africa that is more nostalgic and fantasized than it is real.

Conclusion:

In the complex equation of reconciling pre- and postcolonial arts education systems in Africa, the continent can still count on the resilient models of some of its cultural traditions, as the foundation for a knowledge in the making. In order for popular consciousness to no longer ironically perceive art as an activity for ”white people", it is now up to African cultural policy-makers to rethink these models. Such restructuring should be carried out around three priorities: an emphasis on research in the history and anthropology of African art so that art teaching is no longer concerned with and dominated by Western documentation; a promotion of “living human treasures”, so that the custodians of ancient techniques can transmit them within a well-defined institutional framework; a revaluation of traditional processes of collaborative, interactive, collectivist or even environmentalist creation, through assembly, recycling, multimedia and land art, and performance techniques, situating creation vis-a-vis its own audience. This is the direction that the doual’art association in Cameroon is already working towards, by involving artists, local populations, public authorities and international partners, in the systematization of public art monuments in Douala since 1996. Its projects also proceed from and engage with situational, experimental, participatory and utilitarian aesthetics—The Statue of New Liberty (1996), The Standpipe (2003), The Gateway of Bessengue (2005), The Sound Garden (2010)—as well as environmental and communication design—Arches of Time (2006), The Palaver Tree (2007), Pascale Column (2010), The Written Words of New Bell (2010), The Celestial Canoe (2011), and Theatre-Source Didier Schaub (2013).

Bibliography:

-Dieterlen, Germaine, « Note sur le totémisme dogon », In : L’Homme, Persée, 1, 1962, pp. 106-110.

-Dugast, Idelette & Jeffreys Mervyn David Waldegrave, L’écriture des Bamum, sa naissance, son évolution, sa valeur phonétique, son utilisation, Editions L. C. L., 1950, p.109.

-Laude, Jean, Les arts de l’Afrique noire, éd., Librairie Générale Française, 1966, p.345.

-Matateyou, Emmanuel, L’écriture du Roi Njoya, édition Harmattan, 2015, p. 336.

-Mbembé, Achille, « La colonie : son petit secret et sa part maudite », Politique Africaine, 102, 2006, pp.101-127.

-Njock Nyobé, « La conception du patrimoine au Cameroun postcolonial : enjeux et défis des acteurs », In : Martin Drouin, Lucie K. Morisset & Michel Rautenberg (dir.), Les confins du patrimoine, Presses de l’Université du Québec, 2019, pp.157-198.

-Perrois, Louis & Notué Jean- Paul, Rois sculpteurs de l’Ouest Cameroun, La panthère et la mygale, Paris, Karthala et Orstom, 1993, p.388.

-Tardits, Claude, Le royaume Bamoum, Paris, Ed. Publications de la Sorbonne, Librairie A. Colin, 1980, p.1078.

-Tchandeu, Narcisse Santores, « Rock art in Cameroon, Knowledge, new discoveries and contribution to the sub-regional iconography». In : K. Sahr, A. Esterhusyen, & C. Sievers (eds), African Archaeology without Frontiers: Papers from the 2014 PanAfrican Archaeological Association Congress, Johannesburgh, Witz University Press : 85, 2016, pp. 85-113.

-Tchandeu, Narcisse Santores, « Mythogramme », « pictogramme » et « ludogramme » : à l’origine de l’art, de la proto-écriture et du jeu dans l’iconographie rupestre au Cameroun. Trans, 20, 2017.

-Willet, Franck, L’Art africain, Paris, Thames & Hudson S.A.R.L, 1990, p. 285.

In the complex equation of reconciling pre- and postcolonial arts education systems in Africa, the continent can still count on the resilient models of some of its cultural traditions, as the foundation for a knowledge in the making. In order for popular consciousness to no longer ironically perceive art as an activity for ”white people", it is now up to African cultural policy-makers to rethink these models. Such restructuring should be carried out around three priorities: an emphasis on research in the history and anthropology of African art so that art teaching is no longer concerned with and dominated by Western documentation; a promotion of “living human treasures”, so that the custodians of ancient techniques can transmit them within a well-defined institutional framework; a revaluation of traditional processes of collaborative, interactive, collectivist or even environmentalist creation, through assembly, recycling, multimedia and land art, and performance techniques, situating creation vis-a-vis its own audience. This is the direction that the doual’art association in Cameroon is already working towards, by involving artists, local populations, public authorities and international partners, in the systematization of public art monuments in Douala since 1996. Its projects also proceed from and engage with situational, experimental, participatory and utilitarian aesthetics—The Statue of New Liberty (1996), The Standpipe (2003), The Gateway of Bessengue (2005), The Sound Garden (2010)—as well as environmental and communication design—Arches of Time (2006), The Palaver Tree (2007), Pascale Column (2010), The Written Words of New Bell (2010), The Celestial Canoe (2011), and Theatre-Source Didier Schaub (2013).

Bibliography:

-Dieterlen, Germaine, « Note sur le totémisme dogon », In : L’Homme, Persée, 1, 1962, pp. 106-110.

-Dugast, Idelette & Jeffreys Mervyn David Waldegrave, L’écriture des Bamum, sa naissance, son évolution, sa valeur phonétique, son utilisation, Editions L. C. L., 1950, p.109.

-Laude, Jean, Les arts de l’Afrique noire, éd., Librairie Générale Française, 1966, p.345.

-Matateyou, Emmanuel, L’écriture du Roi Njoya, édition Harmattan, 2015, p. 336.

-Mbembé, Achille, « La colonie : son petit secret et sa part maudite », Politique Africaine, 102, 2006, pp.101-127.

-Njock Nyobé, « La conception du patrimoine au Cameroun postcolonial : enjeux et défis des acteurs », In : Martin Drouin, Lucie K. Morisset & Michel Rautenberg (dir.), Les confins du patrimoine, Presses de l’Université du Québec, 2019, pp.157-198.

-Perrois, Louis & Notué Jean- Paul, Rois sculpteurs de l’Ouest Cameroun, La panthère et la mygale, Paris, Karthala et Orstom, 1993, p.388.

-Tardits, Claude, Le royaume Bamoum, Paris, Ed. Publications de la Sorbonne, Librairie A. Colin, 1980, p.1078.

-Tchandeu, Narcisse Santores, « Rock art in Cameroon, Knowledge, new discoveries and contribution to the sub-regional iconography». In : K. Sahr, A. Esterhusyen, & C. Sievers (eds), African Archaeology without Frontiers: Papers from the 2014 PanAfrican Archaeological Association Congress, Johannesburgh, Witz University Press : 85, 2016, pp. 85-113.

-Tchandeu, Narcisse Santores, « Mythogramme », « pictogramme » et « ludogramme » : à l’origine de l’art, de la proto-écriture et du jeu dans l’iconographie rupestre au Cameroun. Trans, 20, 2017.

-Willet, Franck, L’Art africain, Paris, Thames & Hudson S.A.R.L, 1990, p. 285.

Note

1) Curated by Nora Philippe between April and May 2018 at the Maison Rouge in Paris, this exhibition features black dolls collected by Debbie Neff and made by black nannies in the United States between 1840 and the mid-20th century.

related content

people – 08 jan. 2021

Narcisse Santores Tchandeu

people – 11 sep. 2019

Aude Mgba

blog Aude Mgba – 11 jan. 2021

My learning is affected by the condition of my life

A project by Aude Christel Mgba in the framework of Future of (art) school

partners – 12 jun. 2019