Erik Viskil

peopleErik Viskil is a researcher, writer, lecturer and advisor in the field of contemporary art and design, and a film enthusiast. Over the years he has organized film programmes and lecture series on cinema, in cooperation with various parties. He has curated seminars and a conference on American underground cinema, highlighting the views and works of Jonas Mekas. He has made film programmes and given lectures on the German Red Army Faction and the hallucinatory effects of cinema. Erik was the architect of the new programme of BEAR Fine Art in Arnhem in 2012. He is a tutor at PhD Arts in Leiden and chair of the Examination Board of Design Academy Eindhoven.

Erik curated the filmprogramma of Revolte and gave a lecture as a introduction to the film festival on 7 November and introduces the films on 9 november:

The Revolution Will Come Unexpected – Introduction To The Film Festival

Erik curated the filmprogramma of Revolte and gave a lecture as a introduction to the film festival on 7 November and introduces the films on 9 november:

The Revolution Will Come Unexpected – Introduction To The Film Festival

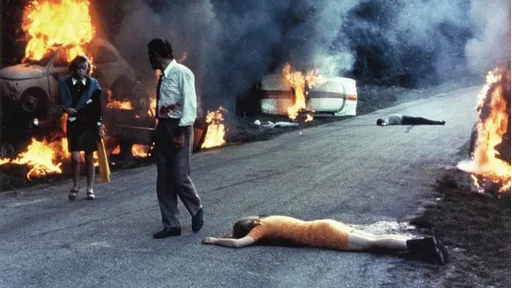

Still from Jean-Luc Godard’s Week-end, 1967

How to remember an event that ultimately led to harsh dictatorship, injustice and war? Could we celebrate the 100th birthday of the Russian Revolution? Even if the ideals might still be valid … the doctrine is not. But there is one thing we can celebrate: the compassion for and belief in the power of the avant-garde. The Russian Revolution gave us a totally renewed language of cinema. It showed us how sharp-witted, socially committed, experimental and pioneering cinema can be.

That was one of my reasons to propose the film programme How To Make A Molotov-Cocktail? The Cinema of Revolution. Not intending to stop at the Russian Revolution, but to start from it, discovering films with a similar attitude and energy. My second starting point was a short activist film which the title of the programme refers to. It was made by the film student Holger Meins in 1968. The film got lost, Holger Meins died in prison, and his fellow students continued with the camera. We will show Gerd Conradt’s Farbtest – Die Rote Fahne and Harun Farocki’s Videogramme einer Revolution.

Erik Viskil’s lecture is a kaleidoscopic preamble to the festival day, with many links to the rest of the programme. He will introduce the films and the directors, and their connections to other highlights of cinema. He will talk about Rainer Werner Fassbinder, who once shouted “I don’t throw bombs, I make films” and about his compelling discussion with his mother about dictatorship in Deutschland im Herbst. A discussion which is now mirrored in Jehane Noujaim’s overwhelming documentary about the Egyption Revolution at Tahrir Square. He will define what a film essay is, and what the importance is of Chris Marker and his relation with Jean-Luc Godard. He will show some stunning stills from Week-end and compare it to La Chinoise, Godard’s other film which explicitly deals with revolution. He will show you the place where the Arab spring began so unexpectedly. And last but not least, he will show you a bright reconstruction of Holger Meins’ lost activist student film from 1968 which was one of the sources of inspiration for the programme.

How to remember an event that ultimately led to harsh dictatorship, injustice and war? Could we celebrate the 100th birthday of the Russian Revolution? Even if the ideals might still be valid … the doctrine is not. But there is one thing we can celebrate: the compassion for and belief in the power of the avant-garde. The Russian Revolution gave us a totally renewed language of cinema. It showed us how sharp-witted, socially committed, experimental and pioneering cinema can be.

That was one of my reasons to propose the film programme How To Make A Molotov-Cocktail? The Cinema of Revolution. Not intending to stop at the Russian Revolution, but to start from it, discovering films with a similar attitude and energy. My second starting point was a short activist film which the title of the programme refers to. It was made by the film student Holger Meins in 1968. The film got lost, Holger Meins died in prison, and his fellow students continued with the camera. We will show Gerd Conradt’s Farbtest – Die Rote Fahne and Harun Farocki’s Videogramme einer Revolution.

Erik Viskil’s lecture is a kaleidoscopic preamble to the festival day, with many links to the rest of the programme. He will introduce the films and the directors, and their connections to other highlights of cinema. He will talk about Rainer Werner Fassbinder, who once shouted “I don’t throw bombs, I make films” and about his compelling discussion with his mother about dictatorship in Deutschland im Herbst. A discussion which is now mirrored in Jehane Noujaim’s overwhelming documentary about the Egyption Revolution at Tahrir Square. He will define what a film essay is, and what the importance is of Chris Marker and his relation with Jean-Luc Godard. He will show some stunning stills from Week-end and compare it to La Chinoise, Godard’s other film which explicitly deals with revolution. He will show you the place where the Arab spring began so unexpectedly. And last but not least, he will show you a bright reconstruction of Holger Meins’ lost activist student film from 1968 which was one of the sources of inspiration for the programme.

related content