dis-membered / re-membered

contested pasts, archives, and counter-memories of diaspora

essay by Asli Özgen – 04 jul. 2023topic: Bodies and Breath: Embodied Research & Writing

“What do we hold in our palms and recall in our fleeting dreams when we look at archival records that are not our own, if not the collective bind to life that compels us to exist despite the certainty of state archives which retrieve a story of loss and obliteration?”

Urged by the irretrievable loss of her grandmother's memories of displacement, as a member of Bulgarian-born Turkish-speaking Muslim minority who experienced displacement and exile from Bulgaria in the 1950s, Asli's research pieces together a complex map of items scattered across various archives to encounter the fragile memories of Turkish diaspora in the Netherlands.

"The loss of stories sharpens the hunger for them," Asli writes in Saidya Hartman's words. As a researcher, she follows the gaps and silences in archives, of the intergenerational memory of migrant, diasporic, exiled communities of women. As a film scholar, she studies the audiovisual heritage of ethnicised and radicalised diasporic communities - looking at the tension between how diasporic subjects are seen by the state versus how they see and narrate themselves.

Every now and then we are gifted with the craft of a writer whose imagination compels us to endow meaning each time we encounter the jagged edges of a memory, a story, or a picture. Every now and then we encounter the craft of a writer whose imagination compels us to transform our restless curiosities into accurate steps and decisiveness to endow meaning to what we do and refuse to do.

Moving in and out of the confines of state archives, Asli’s approach to research and writing, is an invitation to be attentive to the vast and deep frequencies of everyday life of people whose boundedness to histories exists beyond the presence of the silence in the archive.

Urged by the irretrievable loss of her grandmother's memories of displacement, as a member of Bulgarian-born Turkish-speaking Muslim minority who experienced displacement and exile from Bulgaria in the 1950s, Asli's research pieces together a complex map of items scattered across various archives to encounter the fragile memories of Turkish diaspora in the Netherlands.

"The loss of stories sharpens the hunger for them," Asli writes in Saidya Hartman's words. As a researcher, she follows the gaps and silences in archives, of the intergenerational memory of migrant, diasporic, exiled communities of women. As a film scholar, she studies the audiovisual heritage of ethnicised and radicalised diasporic communities - looking at the tension between how diasporic subjects are seen by the state versus how they see and narrate themselves.

Every now and then we are gifted with the craft of a writer whose imagination compels us to endow meaning each time we encounter the jagged edges of a memory, a story, or a picture. Every now and then we encounter the craft of a writer whose imagination compels us to transform our restless curiosities into accurate steps and decisiveness to endow meaning to what we do and refuse to do.

Moving in and out of the confines of state archives, Asli’s approach to research and writing, is an invitation to be attentive to the vast and deep frequencies of everyday life of people whose boundedness to histories exists beyond the presence of the silence in the archive.

dis-membered / re-membered

contested pasts, archives, and counter-memories of diaspora

“no one remembered her name or recorded the things she said,

or observed that she refused to say anything at all.”

– Saidiya Hartman

or observed that she refused to say anything at all.”

– Saidiya Hartman

I

A memory that’s not mine

A memory that’s not mine

When Tamer El Said handed over to me the stack of family photos that he had borrowed to exhibit in his new installation at Berlinale, a memory flashed: my grandma holding my hand in one of those scorching warm summer days in Smyrna. We are walking on the promenade. I can’t remember who took our photo. But I remember the image exactly, I can see it before my eyes: We are standing before the Passport Pier, one of the most iconic buildings in the historic waterfront of Izmir. The waters of the Aegean Sea are splashing calmly against the concrete walls of the waterfront, releasing a salty odour. The sun is burning our skin.

El Said’s installation, entitled Borrowing a Family Album (2023), tackles the absence of family media; photos, albums, movies, which records private histories. His question, when putting together the installation, was “Could images of places I never saw as a child help me to retrieve a disoriented memory? Could we explore stories about ourselves in memories belonging to people we never met?” The mixed-media installation consisted of a glass exhibit in which ‘borrowed’ family photos were spread. On the glass closet, there were reproductions of the photos in boxes. Visitors were invited to look through these photos, choose one or two, and paste it in one of the empty photo albums available, then write down a piece of memory. It could be real, or could be a story, poem, or a few lines inspired by the image. The once empty albums, filled at the end of each day with stories, memories, daydreams that many visitors attached to photos of people they never knew and places they never saw became a family album – a family of hundreds of visitors that didn’t know each other.

Above this glass exhibit hanged a three-channel video, placed along a horizontal line next to each other, in a way to remind early cinematic experiments with panorama. To me, seeing the pictures of the installation recalled early stereoscopic photographs, which persistently brought together exactly the same image, to create the illusion of three-dimensionality when viewed through a device called stereoscope. In a way, these images were put next to each other to envelop the visitor’s body in the affective sphere of memories recorded. Thus, the encounter between the visitor and the image is constructed to activate forgotten instances, images, emotions.

But I’m pretty sure that I have a picture with grandma that looks exactly like this image in the exhibition. I immediately video-call my mother, asking her to send to me that photo of me and grandma in front of the Passport Pier. She cannot recall it. She is going through a box of photos, sends me a few pictures, but that photo in my memory seems non-existent. At least in that box -- which I cannot hold in my hands or access, for I’m miles away. Where did I see this image? Could it be that my mind is projecting a memory, an ephemeral moment, on this photo of people I never met, a place I’ve never been, a time I never lived?

Could it be that I remember a memory that’s not mine? (Jeanine van Berkel)

Could it be that I remember a memory that’s not mine? (Jeanine van Berkel)

In this short piece, I want to dwell on El Said’s provocative question: Could images of places and people we never met help us retrieve a disoriented memory? What happens to these ephemeral memories in the absence of photographic, moving image, or auditory footage? Can we borrow a family album to retrieve or reconstruct forgotten memories?

Exhibited in Berlinale this year, El Said’s installation had as its starting point a traumatising memory that has been haunting the family: Upon the sudden loss of his sister as a little girl, all family photos have been destroyed. While the value of home movies and private media are widely studied, for example for their function to address social history, untold memories, silences in the nation-based histories, and enact counter-memory, the absence of family media has not been widely studied. While such absence could be the deliberate choice of a family to erase a hurtful memory as a way to deal with trauma, it could also have other factors; such as socio-economic ones as in not being able to afford the equipment to produce family media, and political ones as in not being able to keep family media due to forced displacement, exile, migration, or imminent threats in a violent state. How to deal with such absences and destruction? Who gets to produce and keep memory registers?

How does one tell impossible stories? (Saidiya Hartman)

How to activate the counter-memories when there are no records of them in any form whatsoever? I’m interested in the loss of transgenerational memory, due to migration, forced displacement, and exile. Can objects, places, smells activate such (communal) counter-memories? Can archives activate communities, more so than communities activating archives?

How does one tell impossible stories?

How does one tell impossible stories? (Saidiya Hartman)

How to activate the counter-memories when there are no records of them in any form whatsoever? I’m interested in the loss of transgenerational memory, due to migration, forced displacement, and exile. Can objects, places, smells activate such (communal) counter-memories? Can archives activate communities, more so than communities activating archives?

How does one tell impossible stories?

II

loss

loss

I wasn’t there when my grandmother passed away in 2019. I was miles away, trying to finish grading exam papers by the deadline. When my mother video-called and asked if I wanted to speak to grandma, I kept it short. She was sitting on her couch, she looked fine other than swollen feet. Sometimes she sounded confused. Our voices didn’t synch. I kept it short. I went back to work. Mom and aunt stayed with her as she worsened. They booked an appointment with her doctor for the next morning. Later that night, she passed away in her sleep. As she was falling asleep, she was hallucinating, asking when I would go to bed and crawl by her side – mom told me later, in a phone call. Her body remembered, as she was lying in her bed, all those nights that I as a kid would cuddle in bed with her, to find peace and refuge in a turbulent household. Her body remembered. An enormous absence filled my chest. A suffocating silence transpired, as I stood speechless with the phone in my hand, listening to nothingness.

There are many silences in my family. Traumatising events, embarrassing choices, hurtful experiences are not spoken about. My grandmother was born in Bulgaria in 1936. As a member of Turkish-speaking Muslim minority, she endured many attacks by the regime as a child. Their livestock and farm were confiscated, driving them first to starvation and then to forced exile in the aftermath of the second world war. She was banned from school. Her home was constantly raided by the militias. She and her sisters were told to hide. One day in late summer, the whole community was declared undesirable. Deportations began.

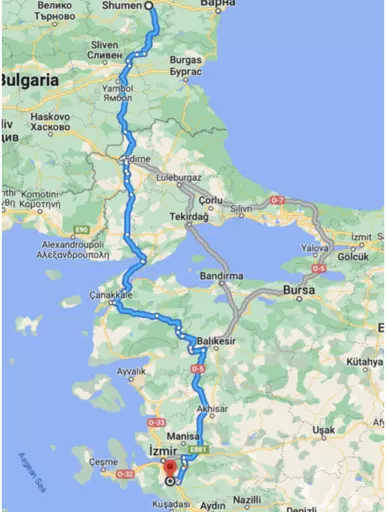

It was fall. They probably were taken by train from Shumen to Edirne, where a camp was set up to receive the sudden influx of refugees. Grandma never really told the story in full, except for a few staggering details in the form of passing jokes or scattered comments here and there: How she had to walk for days in cold without proper shoes; how they had to leave everything behind; how they waited night and day on train tracks; how they departed from the rest of the family and continued the journey to Izmir; how she was lucky to find work immediately after as a cleaner at a school – ironically, attended by pupils of her age. She never could go back to school. Still, she was proud for having learnt to read and write amidst all that precarity.

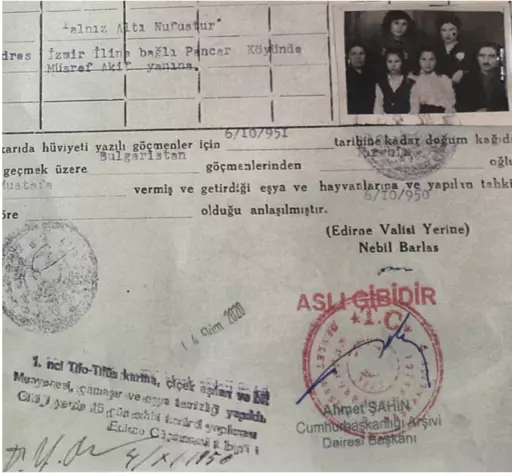

A fragile document from Turkish state archives shows her as a young girl, with her three other sisters and parents, crossing the Turkish border in October 1950. I look closely at the photograph. Outside of its context, it would look like a happy family portrait. Four young girls, parenthesised by their parents: mother on the left, father on the right. The oldest sister is wearing a white rose on her chest, extending her hand in a caring, protective gesture towards the two youngest sisters in the front. Grandma is wearing a white shirt. Her younger sister has a bodywarmer, and flowers in her hair. This is how the Turkish state first ‘saw’ her.

Is this how she took the train, how she walked in cold, waited in the camp for days?

An impossible dialogue.

Is this how she took the train, how she walked in cold, waited in the camp for days?

An impossible dialogue.

“All the refugees entered Turkey at the frontier station of Edirne, after first being concentrated in Svilengrad by the Bulgarian government and then shipped by train to the border station. During the winter of 1950, the refugees suffered greatly both in Svilengrad and Edirne because of lack of housing and feeding facilities. Most of them had lost all of their possessions in Bulgaria and were destitute.”

(Kostanick, The Middle East Journal, 1955)

(Kostanick, The Middle East Journal, 1955)

Did she have anything to eat? Could she sleep in a warm bed after a long journey, have a warm shower before the picture was taken? What did they do if all their money was confiscated?

“Upon arrival at a special railway station built for them, the refugees were given ‘DDT’ treatment and typhoid and smallpox innoculations, and had their clothes disinfected. Their Bulgarian passports and Turkish visas were examined, they completed forms for registration of Turkish citizenship, were screened by security police, and given another medical check. Their particular occupations and abilities were surveyed and their preferences for settlement in particular areas noted. Normally, this process took only a few days, during which they stayed in reception camps, where sleeping and feeding accommodations were provided. Because of the huge number of refugees and the government's inability to supply sufficient personnel and supplies, accommodations were often overcrowded, and in many cases it was impossible to make more than a cursory check of occupational qualifications.” (Kostanick, The Middle East Journal, 1955)

Were you scared? Was this memory the reason you were so dedicated to keeping me safe with your warm cuddles?

Every sentence in the document tells me something, yet doesn’t tell me anything. There is a list of vaccinations and medical examinations they underwent. It also says, “Laundry and goods were cleaned.”

Did you have to change for the picture? To give a good impression? To seem worthy of ‘being let in’ in the eyes of the state?

Every sentence in the document tells me something, yet doesn’t tell me anything. There is a list of vaccinations and medical examinations they underwent. It also says, “Laundry and goods were cleaned.”

Did you have to change for the picture? To give a good impression? To seem worthy of ‘being let in’ in the eyes of the state?

“From Edirne the refugees were sent either to Tekirdag, a port on the Sea of Marmara, or to Istanbul. From these two centers they were assigned to provincial capitals, to which they were transported either by sea or by land at government expense.” (Kostanick, The Middle East Journal, 1955)

So, this is how you came to Izmir. Groups of refugees were spread to villages where they could work on the land. My grandma’s family were taken to Pancar [pandjar] village, near Selcuk, near Ephesus, south of Smyrna/Izmir. In the region’s turbulent history of migration, i.e. forced displacements, or ‘population exchanges,’ Pancar had its own share. Originally a Greek village, its inhabitants were expelled in the 1920s. The fertile lands in this region were important for farming cotton, opium, olive products, and tobacco – and have been home to Levantines, including Dutch settlers in the 19th century until the fall of the Ottoman Empire.

There aren’t many details on how Bulgarian refugees were transported after the boat from Tekirdag. Travelling from north to south via train along the Western coast is virtually impossible, so they must have been transported by busses. Climbing up and down the mountainous landscapes. Did they remind you of your home? If by road, they must have entered the city from the north. Did you see Passport Pier as you were being taken by bus to your new home? Did you dream about walking on the waterfront on a warm summer day, the sea releasing a salty odour?

My earliest memories with grandma are located in my parents’ flat in the city. My father had a night shift and my mother worked during the day. I was brought up by my grandmother. I had extended stays with her in the village. On crisp mornings we walked to the tobacco and cotton farms. On scorching summer days, we took a break at one of those shabby shelters in the middle of farms reaching as far as the horizon. There was always a water well to freshen up in the shade. A refreshing sip of water to catch your breath and rest your body after a long walk to or back from the farms. How did she feel taking care of me when she had to work on the land?

Was I a burden?

Was I a burden?

III

silences

silences

As a researcher, I’m intrigued by silences, absences, gaps in archives, especially concerning the intergenerational memory of migrant, diasporic, exiled communities (of women). Both cultural memory and institutional memory, such as archives, are quiet when it comes to the heritage and memory of migrants and refugees. In the same way as grandma’s memory of exile has vanished in between two states –– i.e. a hostile homeland and an assimilatory host country ––, I’m intrigued by the counter-memories of migrants from Turkey in the Netherlands, my chosen home. “The loss of stories sharpens the hunger for them,” says Saidiya Hartman.1) My concern for the endangered memories of the Turkish diaspora is, in a way, stimulated by the irretrievable loss of my grandma’s memories of displacement. It took me a while to realise this connection, and reflect on my own journey as a first-generation migrant academic.

“I don’t belong to the same history, but the same oppressed body.” (Kexin Hao)

As a film scholar, my interest lies specifically in the audiovisual heritage of ethnicised and racialised diasporic communities. Here there is always a tension between how diasporic subjects are seen by the state versus how they saw and narrated themselves. While the former might be plenty, the latter is largely irretrievably lost. How do presences and absences in archives tell different stories concerning contested pasts, forced displacement, dispossession, trauma, and other forms of violence and violations committed by the state(s)?

“How and where in the archive does one house trauma, fractures, dissociations, elisions?” (Hanna Dawn Henderson)

Can one read absences in archives? Lend an ear to silences? Where do they speak and how? Is it possible to recover memories in impossible dialogues?

Or, in encounters with other images?

Since over a year I’m trying to map out the audiovisual heritage of the diasporic community from Turkey across archival institutions in the Netherlands. I’m interested in a wide range of formats extending from photographs to printed materials such as posters, brochures, newspapers, magazines; to filmic material such as 16mm and 35mm reels, VHS tapes, and broadcast content; to radio collections and audio letters. My starting point was the hypothesis that there wasn’t “much” in the archives, just as the case with any diasporic audiovisual heritage in host countries. While all may not be lost, the diasporic audiovisual heritage of Turkish communities is overwhelmingly fragmented, scattered, precarious, invisible, and inaudible. This seems to be characteristic when it comes to diasporic heritages. Due to its invisibility in cultural memory at present, I hadn’t expected to find so many artefacts in the archives. Nor had I expected that the historical and archival silences concerning migrant and diasporic communities in state archives would have so many overlaps.

It’s crucial to underline that the audiovisual heritage of the Turkish community in the Netherlands is anything but homogeneous, uniform. There are substantial challenges arising from the sheer expanse, messiness, and heterogeneity of items. My ongoing research into locating this audiovisual heritage in the Netherlands has so far brought up a complex map of items scattered across various archives. These include Eye Filmmuseum, Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision, International Institute for Social History, and Atria: Institute for Women’s History. Furthermore, The National Archive in The Hague as well as regional archives and city archives hold relevant records. The archives of companies, migration centra, political organisations, and cultural foundations established by the Turkish and Kurdish minority are extremely valuable, yet also undeniably precarious. To this we must add personal archives or family collections which are perhaps the most vulnerable in this overview.

In Lied uit den Vreemde, Jaap Vogel and Erhan Tuskan underline the importance of archival documents ––ranging from private and personal collections to all that has survived in the institutional archives–– to retrieve the diversity of lived experiences in the group of workers that came from Turkey.2) This is particularly crucial to undermine the homogenising and stereotypical representations in the (Dutch) media and national imagination. For example, media scholar Andrea Meuzelaar researched how migrants from the SWANA region were almost exclusively encoded as Muslims and how such images were tagged and serviced by archives to television channels, thus consolidating such representations and stereotypes.3) However, not all migrants from Turkey identified as Muslims, plus practices of Islam differed among different groups and regions to a large extent. In many ways, as Vogel and Tuskan remind us, in the Turkish community in the Netherlands, a mirror reflection of the tensions and alliances in the home country existed. There were divides between Sunni and Alevi communities as well as between progressive-thinking left-wing political groupings and conservative right-wing circles. Besides, not all workers that came from Turkey identified as Turkish. There is a sizeable Kurdish community, specifically political refugees that fled in the wake of increasing state violence and authoritarianism, which culminated in a violent military coup in 1980. Not to forget the influx of women workers, who founded women-only organisations and political groups to fight for their struggle. On top of this, the history of migration from Turkey to the Netherlands has not been homogeneous, smooth, and steady.4) A nuanced approach to the diasporic audiovisual heritage of post-war migrants from Turkey would be attentive, among others, to the diversity of regions, political positions, religions, and languages among them. Reconsidered from this standpoint, the audiovisual heritage of the post-war migrant communities from Turkey appears much more diverse, broad, and multifaceted.

The extant materials in archives might give the illusion of presence; however, the link between existence and presence should not be envisioned as that straightforward when it comes to the diasporic heritage of the migrant and exiled. First, the majority of archived items are registers from the perspective of the state, representing only a partial story (e.g. the archives of migration centra, factory registers, police records as well as many images/narratives circulating in media). What Terry Cook calls “citizen-state interactions.”5) Second, the archives of communities such as political parties, solidarity groups, associations set up by migrants remain only partially safeguarded, for example at the International Institute for Social History, with a substantial part of it being still at risk. Third, due to many issues and shortcomings in archival processes, the extant items remain marginalised and/or inaccessible in their host institutions, meaning that they are not seen or heard, or made part of the cultural history and memory at present in a meaningful way. Even though they exist, they are quiet. How to activate them, how to make them speak? Can one speak back to these partial stories? Or, speak otherwise?

We can lend an ear to two culture thinkers. First, Stuart Hall’s influential piece ––“Unsettling ‘the heritage’, re-imagining the post-nation: Whose heritage?”, which had a great impact on Critical Heritage Studies–– explores ways to unsettle the imagined community of the nation as a determining factor in the discourse and practice of heritage.6) Hall argues for re-imagining the nation as diverse, inclusive, in-becoming; and heritage as continuing, open-ended, living. Heritage and memory are not about the past, they are about the present with an eye onto the future.

Such a re-imagining must start with rewriting “the margins to the centre, outside into the inside."7) Here, let's turn to bell hooks and her conceptualisation of margin. Margins, for bell hooks, are political locations (or, positionalities if you like) from where counter-hegemonic cultural practices could emerge. In the article “Choosing the Margin as a Space of Radical Openness,” hooks re-conceptualises the margin both as a site of exclusion and as a site of resistance.8)

Re-centring the marginalised archival artefacts is possible through re-centring the marginalised communities, memories, and voices. Rewriting the margins into the centre, to borrow the expression of Stuart Hall, should be envisioned as a collective act where the archives and the communities actively encounter and activate each other.9) How does one encounter and confront the archives?

“I don’t belong to the same history, but the same oppressed body.” (Kexin Hao)

As a film scholar, my interest lies specifically in the audiovisual heritage of ethnicised and racialised diasporic communities. Here there is always a tension between how diasporic subjects are seen by the state versus how they saw and narrated themselves. While the former might be plenty, the latter is largely irretrievably lost. How do presences and absences in archives tell different stories concerning contested pasts, forced displacement, dispossession, trauma, and other forms of violence and violations committed by the state(s)?

“How and where in the archive does one house trauma, fractures, dissociations, elisions?” (Hanna Dawn Henderson)

Can one read absences in archives? Lend an ear to silences? Where do they speak and how? Is it possible to recover memories in impossible dialogues?

Or, in encounters with other images?

Since over a year I’m trying to map out the audiovisual heritage of the diasporic community from Turkey across archival institutions in the Netherlands. I’m interested in a wide range of formats extending from photographs to printed materials such as posters, brochures, newspapers, magazines; to filmic material such as 16mm and 35mm reels, VHS tapes, and broadcast content; to radio collections and audio letters. My starting point was the hypothesis that there wasn’t “much” in the archives, just as the case with any diasporic audiovisual heritage in host countries. While all may not be lost, the diasporic audiovisual heritage of Turkish communities is overwhelmingly fragmented, scattered, precarious, invisible, and inaudible. This seems to be characteristic when it comes to diasporic heritages. Due to its invisibility in cultural memory at present, I hadn’t expected to find so many artefacts in the archives. Nor had I expected that the historical and archival silences concerning migrant and diasporic communities in state archives would have so many overlaps.

IV

speak back, with, otherwise

speak back, with, otherwise

“Archives have never been about truth. They are partially about evidence – evidence catalyzed in support of a claim.” (Michelle Caswell)

Jacques Derrida, Michel Foucault, Achille Mbembe, Stuart Hall, Terry Cook… Many thinkers have pointed to the role of archives in upholding power, authority, and the imagined community of nationhood. “The power of the archive is witnessed in the act of inclusion, but this is only one of its components,” says Rodney G. S. Carter; “the power to exclude is a fundamental aspect of the archive.” Archives, thus, are never complete; they are never about completeness. As Carter summarises, “there are distortions, omissions, erasures, and silences in the archive.”10)

“Not every story is told.” (Rodney Carter)

Studying gaps, absences, and silences in the archives does not strive towards a simple filling in the blanks. Verne Harris warns us that archivists should resist the urge to speak for others.11) It is tempting to fill in the gaps and to provide closure where there is none.

Rather, studying gaps, absences, and silences is an endeavor that explores how the powerful introduces “silences into the archives by denying marginal groups their voice and the opportunity to participate in the archives.”12) In other words, this endeavor strives to expose the epistemic injustice and violence that underlie the very existence of archival institutions. It seeks to transform archival processes, from acquisition to appraisal, from cataloguing to metadata, to preservation, restoration, and access. Thus, simply adding material to existing archival institutions without challenging and radically transforming the dominant and restrictive archival categories, practices, and systems will not suffice. The gaps, silences, and absences are not results of unfortunate accidents; they themselves constitute the epistemic regime of the archive.

“What is at issue here […] is the violence of archive itself, as archive, as archival violence.” (Jacques Derrida)

In the face of growing engagement with archives and their constitutive limits, many scholars, practitioners, communities have been imagining various ways to unsettle these epistemic regimes. For example, positioning herself as an activist/archivist, Michelle Caswell has been an influential voice in spotlighting the bias in appraisal decisions, which masquerades as neutral.13) According to Caswell, “there has been a lack of care among memory institutions when it comes to archiving and documenting communities of color, LGBTQ communities, and people who are marginalised due to beliefs, geography, and social class.”14) Pointing to a direct link between archival practices and social justice, Caswell sees it as an obligation to center those people who have been marginalised in the appraisal decisions. Similarly, in descriptions, it's crucial to use the same languages that communities use to describe themselves. Here the texts, tags, keywords used in catalogue descriptions eventually impact the findability and, thus, access. Community engagement on all these levels is vital for archival and social justice.

Crucially, the proposition here does not mean bringing communities in the service to the institutional archives (in some cases, of their oppressor). Carter reminds us that while silences can be contested ad the marginalised can be invited in, “it must be recognized that these groups may not accept this invitation.”15) Rather, centring communities in decision making processes in archives could be a first step to restoring epistemic justice, through disrupting, subverting, and transforming archival processes. While safeguarding precarious audiovisual heritage at present is crucial (Stuart Hall’s living archive), in some cases communities might prefer not to be annexed to the memory institution of their oppressor, settler, coloniser. In the context of contested pasts and violence, communities and persons may not want to be ‘seen’ by the state. In these cases of ‘chosen absence’, silences can become effective tools to voice resistance, a form of self-assertion. Some marginalised and/or excluded communities may choose to act outside of the archive, for example, by setting up a community archive. All in all, the fantasy of a ‘totalistic’ archive that at once records and registers all might entail a latent (colonialist) surveillance logic, and thus may not be the ultimate solution to undermine the power of the archive over societal memory and history.

How to respect the limits of what cannot be known? (Saidiya Hartman)

“You have all this history, all of this knowledge, and what does it really amount to?” (Patricia Saunders)

Jacques Derrida, Michel Foucault, Achille Mbembe, Stuart Hall, Terry Cook… Many thinkers have pointed to the role of archives in upholding power, authority, and the imagined community of nationhood. “The power of the archive is witnessed in the act of inclusion, but this is only one of its components,” says Rodney G. S. Carter; “the power to exclude is a fundamental aspect of the archive.” Archives, thus, are never complete; they are never about completeness. As Carter summarises, “there are distortions, omissions, erasures, and silences in the archive.”10)

“Not every story is told.” (Rodney Carter)

Studying gaps, absences, and silences in the archives does not strive towards a simple filling in the blanks. Verne Harris warns us that archivists should resist the urge to speak for others.11) It is tempting to fill in the gaps and to provide closure where there is none.

“What is at issue here […] is the violence of archive itself, as archive, as archival violence.” (Jacques Derrida)

In the face of growing engagement with archives and their constitutive limits, many scholars, practitioners, communities have been imagining various ways to unsettle these epistemic regimes. For example, positioning herself as an activist/archivist, Michelle Caswell has been an influential voice in spotlighting the bias in appraisal decisions, which masquerades as neutral.13) According to Caswell, “there has been a lack of care among memory institutions when it comes to archiving and documenting communities of color, LGBTQ communities, and people who are marginalised due to beliefs, geography, and social class.”14) Pointing to a direct link between archival practices and social justice, Caswell sees it as an obligation to center those people who have been marginalised in the appraisal decisions. Similarly, in descriptions, it's crucial to use the same languages that communities use to describe themselves. Here the texts, tags, keywords used in catalogue descriptions eventually impact the findability and, thus, access. Community engagement on all these levels is vital for archival and social justice.

Crucially, the proposition here does not mean bringing communities in the service to the institutional archives (in some cases, of their oppressor). Carter reminds us that while silences can be contested ad the marginalised can be invited in, “it must be recognized that these groups may not accept this invitation.”15) Rather, centring communities in decision making processes in archives could be a first step to restoring epistemic justice, through disrupting, subverting, and transforming archival processes. While safeguarding precarious audiovisual heritage at present is crucial (Stuart Hall’s living archive), in some cases communities might prefer not to be annexed to the memory institution of their oppressor, settler, coloniser. In the context of contested pasts and violence, communities and persons may not want to be ‘seen’ by the state. In these cases of ‘chosen absence’, silences can become effective tools to voice resistance, a form of self-assertion. Some marginalised and/or excluded communities may choose to act outside of the archive, for example, by setting up a community archive. All in all, the fantasy of a ‘totalistic’ archive that at once records and registers all might entail a latent (colonialist) surveillance logic, and thus may not be the ultimate solution to undermine the power of the archive over societal memory and history.

How to respect the limits of what cannot be known? (Saidiya Hartman)

“You have all this history, all of this knowledge, and what does it really amount to?” (Patricia Saunders)

V

Dis-membered / Re-membered

Dis-membered / Re-membered

Researching the audiovisual heritage of migrant, exiled, and diasporic communities feels sometimes like forensics work. Collecting scattered remains and traces here and there, trying to make sense of them. At times, trying to reconstruct a crime scene. At times, striving to extract as much information as possible from smallest traces and material details... Elizabeth Ramírez-Soto uses the evocative phrase of a “scattered body” (in her case to describe the Chilean exile cinema).16) If ghosts haunt the archives, we need to know where the bodies and bones lie (Derrida).

I started this essay with the question of archival absences and silences, especially when it comes to migrant and displaced communities. Can images of others be mobilized to activate counter-memories of migrancy? Is it possible to re-member the dis-membered, scattered, destroyed records to retrieve disoriented memories?

Critical fabulation. Telling a story without telling it. “Laboring to paint as full a picture.” “Straining against the limits of the archive” “Enacting the impossibility of representing the lives of the captives precisely through the process of narration.” (Saidiya Hartman)

In my research, I am exploring the possibility of activating counter-memories of migration and exile among the Turkish and Kurdish communities in the Netherlands. What happens when the community encounters the archival records? Even though the records may not concern themselves, could images of others retrieve memories, stories untold? How to speak back to and speak with archives? Besides transforming archival processes that I described earlier, Hartman’s method of critical fabulation provides many possibilities here. While the histories are very different, the silence of archives, the marginalisation of artefacts, and epistemic violence enacted by state archives share many similarities in cases of diasporic communities. This remains a significant question in my research, how do different histories of migration, displacement, and exile share similar archival discontents?

Can we envision or forge a solidarity of epistemic justice across archives?

Here, as a final word, I turn to Caswell’s evocation of affective dimension of such solidarity and struggle for epistemic justice. In many ways, archives are places for affective encounters (Arlette Farge), yet there is seldom any room to store affects, emotions in them. Evoking feminist theorists’, particularly Black feminist thinkers’ critique of the tyranny of reason, Caswell proposes to build “archival theories and practices that heal the false rift between emotion and reason by taking emotion seriously.” She says, “feelings enable us to know,” and cites Audre Lorde “`Our feelings are our most genuine paths to knowledge.” For Caswell, “if we believe that our feelings, and especially the feelings of those who are oppressed, provide substantial grounds from which to know, then we have to radically rethink and redo and reuse archives. And that is what I want us to do: to rethink and redo the work of archives.”17)

Not to fill in the gaps, but to let the gaps speak to us.

Not to speak for the silenced, but to speak back to the violence of silencing.

Not to reconstruct the past, but to speak with the traces of the past to transform the present and the future.

How would confrontation with archives make us feel as eyes turned to absences and ears tuned to silences?

Discomfort.

Disillusionment.

Anger.

Grief.

Joy.

“Will we use our feelings as evidence?” (Caswell)

Going back to Tamer El Said’s provocative question: “Could images of places I never saw as a child help me to retrieve a disoriented memory? Could we explore stories about ourselves in memories belonging to people we never met?”

Encountering archives in this way perhaps could inspire memories of diaspora that were untold, and tell them “without telling” (Hartman). Embracing the unknowable, possibilities, divergences. Betraying the erasures. A storytelling not of cause and effect and chronological continuity, but a storytelling of myriad of moments, affects, discontinuities, ruptures that counter and disrupt the state-sanctioned histories.

Critical fabulation. Telling a story without telling it. “Laboring to paint as full a picture.” “Straining against the limits of the archive” “Enacting the impossibility of representing the lives of the captives precisely through the process of narration.” (Saidiya Hartman)

In my research, I am exploring the possibility of activating counter-memories of migration and exile among the Turkish and Kurdish communities in the Netherlands. What happens when the community encounters the archival records? Even though the records may not concern themselves, could images of others retrieve memories, stories untold? How to speak back to and speak with archives? Besides transforming archival processes that I described earlier, Hartman’s method of critical fabulation provides many possibilities here. While the histories are very different, the silence of archives, the marginalisation of artefacts, and epistemic violence enacted by state archives share many similarities in cases of diasporic communities. This remains a significant question in my research, how do different histories of migration, displacement, and exile share similar archival discontents?

Can we envision or forge a solidarity of epistemic justice across archives?

Here, as a final word, I turn to Caswell’s evocation of affective dimension of such solidarity and struggle for epistemic justice. In many ways, archives are places for affective encounters (Arlette Farge), yet there is seldom any room to store affects, emotions in them. Evoking feminist theorists’, particularly Black feminist thinkers’ critique of the tyranny of reason, Caswell proposes to build “archival theories and practices that heal the false rift between emotion and reason by taking emotion seriously.” She says, “feelings enable us to know,” and cites Audre Lorde “`Our feelings are our most genuine paths to knowledge.” For Caswell, “if we believe that our feelings, and especially the feelings of those who are oppressed, provide substantial grounds from which to know, then we have to radically rethink and redo and reuse archives. And that is what I want us to do: to rethink and redo the work of archives.”17)

Not to fill in the gaps, but to let the gaps speak to us.

Not to speak for the silenced, but to speak back to the violence of silencing.

Not to reconstruct the past, but to speak with the traces of the past to transform the present and the future.

How would confrontation with archives make us feel as eyes turned to absences and ears tuned to silences?

Discomfort.

Disillusionment.

Anger.

Grief.

Joy.

“Will we use our feelings as evidence?” (Caswell)

Going back to Tamer El Said’s provocative question: “Could images of places I never saw as a child help me to retrieve a disoriented memory? Could we explore stories about ourselves in memories belonging to people we never met?”

Encountering archives in this way perhaps could inspire memories of diaspora that were untold, and tell them “without telling” (Hartman). Embracing the unknowable, possibilities, divergences. Betraying the erasures. A storytelling not of cause and effect and chronological continuity, but a storytelling of myriad of moments, affects, discontinuities, ruptures that counter and disrupt the state-sanctioned histories.

Notes

1 Saidiya Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts,” Small Axe 26, no. 2 (June 2008): 8.

2 Erhan Tuskan and Jaap Vogel, Lied uit den Vreemde/Gurbet Türküsü: Brieven en foto’s van Turkse migranten 1964-1975 (Amsterdam: Uitgeverij Aksant, 2004

3 Andrea Meuzelaar, “The Emergence and Persistence of Racialised Stereotypes on Dutch Television: Tracing the History of Representation of Muslim Immigrants along the Archival Grain,” VIEW: Journal of European Television History and Culture 10, no. 20 (2021). Open access at viewjournal.eu

4 Tuskan and Vogel, Lied uit den Vreemde, 1-25.

5 Terry Cook, “Mind over Matter: Towards a New Theory of Archival Appraisal,” in Barbara L. Craig, ed., The Archival Imagination: Essays in Honour of Hugh. A. Taylor (Ottawa: Association of Canadian Archivists), 50.

6 Stuart Hall, “Un-settling ‘the heritage’, re-imagining the post-nation: Whose Heritage?” Third Text 13, no. 49 (1999): 3–13.

7 Hall, “Unsettling the Heritage,” 10.

8 bell hooks, “Choosing Margin as a Space of Radical Openness,” Framework: The Journal of Cinema and Media 36 (1989): 15-23.

9 Hall, “Unsettling the Heritage.”

10 Rodney G.S. Carter, “Of Things Said and Unsaid: Power, Archival Silences, and Power in Silence”. Archivaria 61 (September 2006): 216.

11 Verne Harris, “Seeing (in) Blindness: South Africa, Archives and Passion for Justice,” (2001). Open access at scnc.ukzn.ac.za/doc/LibArchMus/Arch/Harris_V_Freedom_of_Information_in_SA_Archives_for_justice.pdf

12 Carter, “Of Things Said and Unsaid,” 217.

13 Michelle Caswell, “Dusting for Fingerprints: Introducing Feminist Standpoint Appraisal,” Journal of Critical Library and Information Studies 3, no.1 (2019): 10.

14 Michelle Caswell, et al. “Images, Silences, and the Archival Record: An Interview with Michelle Caswell,” disClosure: A Journal of Social Theory 27 (2018), 24. Open access at uknowledge.uky.edu/disclosure/vol27/iss1/7

15 Carter, “Of Things Said and Unsaid,” 217.

16 Elizabeth Ramírez-Soto, “Habanera: de fragmentos y retornos inacaba- dos,” in Una mirada oblicua: el cine de Valeria Sarmiento, ed. Bruno Cuneo and Fernando Pérez V., 89–101 (Santiago: Universidad Alberto Hurtado, 2021).

17 Michelle Caswell, “Feeling Liberatory Memory Work: On the Archival Uses of Joy and Anger,” Archivaria 90 (November 2020): 153.

2 Erhan Tuskan and Jaap Vogel, Lied uit den Vreemde/Gurbet Türküsü: Brieven en foto’s van Turkse migranten 1964-1975 (Amsterdam: Uitgeverij Aksant, 2004

3 Andrea Meuzelaar, “The Emergence and Persistence of Racialised Stereotypes on Dutch Television: Tracing the History of Representation of Muslim Immigrants along the Archival Grain,” VIEW: Journal of European Television History and Culture 10, no. 20 (2021). Open access at viewjournal.eu

4 Tuskan and Vogel, Lied uit den Vreemde, 1-25.

5 Terry Cook, “Mind over Matter: Towards a New Theory of Archival Appraisal,” in Barbara L. Craig, ed., The Archival Imagination: Essays in Honour of Hugh. A. Taylor (Ottawa: Association of Canadian Archivists), 50.

6 Stuart Hall, “Un-settling ‘the heritage’, re-imagining the post-nation: Whose Heritage?” Third Text 13, no. 49 (1999): 3–13.

7 Hall, “Unsettling the Heritage,” 10.

8 bell hooks, “Choosing Margin as a Space of Radical Openness,” Framework: The Journal of Cinema and Media 36 (1989): 15-23.

9 Hall, “Unsettling the Heritage.”

10 Rodney G.S. Carter, “Of Things Said and Unsaid: Power, Archival Silences, and Power in Silence”. Archivaria 61 (September 2006): 216.

11 Verne Harris, “Seeing (in) Blindness: South Africa, Archives and Passion for Justice,” (2001). Open access at scnc.ukzn.ac.za/doc/LibArchMus/Arch/Harris_V_Freedom_of_Information_in_SA_Archives_for_justice.pdf

12 Carter, “Of Things Said and Unsaid,” 217.

13 Michelle Caswell, “Dusting for Fingerprints: Introducing Feminist Standpoint Appraisal,” Journal of Critical Library and Information Studies 3, no.1 (2019): 10.

14 Michelle Caswell, et al. “Images, Silences, and the Archival Record: An Interview with Michelle Caswell,” disClosure: A Journal of Social Theory 27 (2018), 24. Open access at uknowledge.uky.edu/disclosure/vol27/iss1/7

15 Carter, “Of Things Said and Unsaid,” 217.

16 Elizabeth Ramírez-Soto, “Habanera: de fragmentos y retornos inacaba- dos,” in Una mirada oblicua: el cine de Valeria Sarmiento, ed. Bruno Cuneo and Fernando Pérez V., 89–101 (Santiago: Universidad Alberto Hurtado, 2021).

17 Michelle Caswell, “Feeling Liberatory Memory Work: On the Archival Uses of Joy and Anger,” Archivaria 90 (November 2020): 153.