De zee als metronoom – verwijdering en toenadering als tijdsbeleving

The sea as metronome: estrangement and reconciliation as experiences of time

essay by Laure van den Hout – 19 apr. 2023topic: TIME: the impact of time (pressure) on authorship

Kunnen we tijd maken, tijd voor het niet-weten als productieve kracht? Hoe zorgen we ervoor dat niet ook het makerschap steeds meer ten prooi valt aan de wetten van de kapitalisering? Kan tijd een creatief instrument zijn? In de serie TIJD gaan ArtEZ Studium Generale en Mister Motley hier dieper op in.

Voor deze serie schreef Laure van den Hout het openingsessay De zee als metronoom waarin ze aan de hand van de natuur als eerste klok ingaat op een tijdsbeleving die gevormd wordt door toenadering en verwijdering. Denk aan de maan en de zon – dichterbij en weer verder weg – aan donker en licht, eb en vloed. Aan de hand van water en de verschillende gedaantes waarin dat zich aandient, laat Van den Hout zien dat je niet kunt afdwingen in welke staat je bent op welk uur, dat productiviteit in de mate waarop wij het gewend zijn waarschijnlijk veel te veel een geforceerde staat is. Dat maakbaarheid en maakbare tijd grenzen kennen.

Voor deze serie schreef Laure van den Hout het openingsessay De zee als metronoom waarin ze aan de hand van de natuur als eerste klok ingaat op een tijdsbeleving die gevormd wordt door toenadering en verwijdering. Denk aan de maan en de zon – dichterbij en weer verder weg – aan donker en licht, eb en vloed. Aan de hand van water en de verschillende gedaantes waarin dat zich aandient, laat Van den Hout zien dat je niet kunt afdwingen in welke staat je bent op welk uur, dat productiviteit in de mate waarop wij het gewend zijn waarschijnlijk veel te veel een geforceerde staat is. Dat maakbaarheid en maakbare tijd grenzen kennen.

For the English version please scroll down

Marien bioloog Rachel Carson schrijft in haar indrukwekkende boek De zee over de fascinerende dieptes waaruit wij mensen voortkomen. Hoewel het boek al in 1951 verscheen, is het nog altijd verrassend actueel. Haar holistische visie op de natuur, en de overwegend negatieve invloed die de mens daarop heeft, lees je in alles terug. Eén passage bleef me in het bijzonder bij, waarin Carson een een-op-eenervaring met de zee benoemt als het moment waarop de mens zich realiseert dat hij slechts onderdeel is van een veel groter geheel, een geheel waarin zijn illusie van maakbaarheid schijn is:

‘Hij (de mens, red.) kan de oceaan niet beheersen en veranderen zoals hij in zijn korte verblijf op aarde de andere continenten aan zich heeft onderworpen en geplunderd. In de kunstmatige wereld van zijn steden en dorpen vergeet hij vaak de ware aard van zijn planeet en de lange perioden van haar geschiedenis, waarin het bestaan van het mensenras niet meer is dan een oogwenk. Het besef van dat alles komt hem het helderst voor de geest in de loop van een lange zeereis, als hij dag na dag de door golven geplooide en gegroefde, terugtrekkende rand van de horizon ziet, wanneer hij zich ’s avonds bewust wordt van de draaiing van de aarde doordat de sterren boven hem voorbij wentelen of wanneer hij, alleen in zijn wereld van water en lucht, de eenzaamheid van de aarde in de ruimte voelt. En dan weet hij, wat hij nooit weet op het land, dat het waar is dat zijn wereld een waterwereld is, een planeet die wordt gedomineerd door de mantel van de oceaan die alles bedekt, waarop de continenten slechts een vergankelijke inbreuk zijn van land dat uitstijgt boven het oppervlak van de zee die alles omringt.’

Carson schrijft wonderbaarlijk over de meest onvoorstelbare zaken. Over zeeberen met in hun maag graten van een vissoort waarvan de mens nog nooit een levend exemplaar heeft gezien. Over waarom warmbloedige zoogdieren als baleinwalvissen geen of minder gevaar lijken te lopen voor Caissonziekte (duikersziekte), terwijl ze schijnbaar loodrecht de diepte in duiken en vrijwel onmiddellijk naar de oppervlakte kunnen terugkeren. Ze probeert te verklaren, maar meer nog probeert ze de verwondering te vieren, de verwondering die bij sommigen leidt tot het onderzoeken van de reden die erachter schuilgaat, maar ook de verwondering die in zichzelf al zo wezenlijk is.

Het is de verwondering die ons zachter maakt naar onze omgeving, ons er meer naar doet omkijken, die ons bewust maakt van hoe noodzakelijk al het leven om ons heen is voor ons eigen leven. Die, kortom, meer bescheiden maakt. In deze verwondering keert Carson steeds terug naar tijd als een richtinggevend element. In de eerste plaats als ze in het eerste hoofdstuk, dat de titel ‘Moeder Zee’ draagt, beschrijft hoe de zeeën zijn ontstaan, hoe de natuurlijke ritmes tot wasdom zijn gekomen, hoe de zon en de maan daarin een belangrijke rol spelen, zoals ze ook mede-bepalen welk organisme waar leeft.

Maar ook subtieler, en meer conceptueel: hoe er dieptes zijn waar naartoe we niet of nauwelijks kunnen afdalen, plekken waarvan we aannemen dat er niets leeft (hier is natuurlijk een parallel te trekken met de diepte die de andere kant op gaat: de ruimte). Ons voorstellingsvermogen van wat realistisch is neemt onze eigen voorwaarden voor het bestaan als referentiekader, logisch ook, maar niet zelden onterecht. Op de bodem van de diepzee, verstoken van licht, leven wormen.

‘Hij (de mens, red.) kan de oceaan niet beheersen en veranderen zoals hij in zijn korte verblijf op aarde de andere continenten aan zich heeft onderworpen en geplunderd. In de kunstmatige wereld van zijn steden en dorpen vergeet hij vaak de ware aard van zijn planeet en de lange perioden van haar geschiedenis, waarin het bestaan van het mensenras niet meer is dan een oogwenk. Het besef van dat alles komt hem het helderst voor de geest in de loop van een lange zeereis, als hij dag na dag de door golven geplooide en gegroefde, terugtrekkende rand van de horizon ziet, wanneer hij zich ’s avonds bewust wordt van de draaiing van de aarde doordat de sterren boven hem voorbij wentelen of wanneer hij, alleen in zijn wereld van water en lucht, de eenzaamheid van de aarde in de ruimte voelt. En dan weet hij, wat hij nooit weet op het land, dat het waar is dat zijn wereld een waterwereld is, een planeet die wordt gedomineerd door de mantel van de oceaan die alles bedekt, waarop de continenten slechts een vergankelijke inbreuk zijn van land dat uitstijgt boven het oppervlak van de zee die alles omringt.’

Carson schrijft wonderbaarlijk over de meest onvoorstelbare zaken. Over zeeberen met in hun maag graten van een vissoort waarvan de mens nog nooit een levend exemplaar heeft gezien. Over waarom warmbloedige zoogdieren als baleinwalvissen geen of minder gevaar lijken te lopen voor Caissonziekte (duikersziekte), terwijl ze schijnbaar loodrecht de diepte in duiken en vrijwel onmiddellijk naar de oppervlakte kunnen terugkeren. Ze probeert te verklaren, maar meer nog probeert ze de verwondering te vieren, de verwondering die bij sommigen leidt tot het onderzoeken van de reden die erachter schuilgaat, maar ook de verwondering die in zichzelf al zo wezenlijk is.

Het is de verwondering die ons zachter maakt naar onze omgeving, ons er meer naar doet omkijken, die ons bewust maakt van hoe noodzakelijk al het leven om ons heen is voor ons eigen leven. Die, kortom, meer bescheiden maakt. In deze verwondering keert Carson steeds terug naar tijd als een richtinggevend element. In de eerste plaats als ze in het eerste hoofdstuk, dat de titel ‘Moeder Zee’ draagt, beschrijft hoe de zeeën zijn ontstaan, hoe de natuurlijke ritmes tot wasdom zijn gekomen, hoe de zon en de maan daarin een belangrijke rol spelen, zoals ze ook mede-bepalen welk organisme waar leeft.

Maar ook subtieler, en meer conceptueel: hoe er dieptes zijn waar naartoe we niet of nauwelijks kunnen afdalen, plekken waarvan we aannemen dat er niets leeft (hier is natuurlijk een parallel te trekken met de diepte die de andere kant op gaat: de ruimte). Ons voorstellingsvermogen van wat realistisch is neemt onze eigen voorwaarden voor het bestaan als referentiekader, logisch ook, maar niet zelden onterecht. Op de bodem van de diepzee, verstoken van licht, leven wormen.

In haar boek Artful schrijft Ali Smith in ‘On time’ over een personage wier partner overleden is. Ze loopt door haar woning, de woning die ze met haar partner deelde, ziet hoe hun beider boeken vermengd in de kasten staan (‘the most faithful act of all, mix our separate books into one library’), pakt er een uit. Het is Dickens’ Oliver Twist. Ze heeft sinds het verlies – al een jaar en een dag – niet kunnen lezen. En denkt terug aan wanneer ze het boek in haar handen voor het laatst gelezen heeft: ‘I’d not read Oliver Twist since, oh god, when? way before we even first knew each other, I’d had to, for university, so that made it thirty years. That gave me a shake. A twelvemonth and a day can arguably be called short, but thirty years? How could thirty years be the blink-of-an-eye it felt? It was the difference between black and white footage of the Second World War and David Bowie on Top of the Pops singing Life on Mars; it was the size of a grown woman with four children, one of them nearly old enough, if the woman started very early, to be doing A-levels. They definitely weren’t called A-levels anymore.’

Nog voordat ze kan proberen te gaan lezen, stuit ze op een probleem. De stoel waarin ze wil gaan lezen, was van haar partner: ‘But it was your chair, this chair, even though we’d bought it on my credit card (and it still wasn’t paid off; how unfair that a chair we saw online and bought on a credit card and had delivered in a van would, could, did, last longer than us). And we’d had that argument about moving it several times and you’d always won that argument.’

Haar partners stoel, waarvan zij vond dat die niet op de juiste plek stond. Niet in staat het juiste licht te vangen, te veel op de tocht, te ver van het bureau bovendien. Is het een loyaliteitsbreuk om de stoel nu te gaan versjouwen? Ze doet het. Met brute kracht en opgestroopte tapijten tot gevolg. Het voelt goed. Na luttele minuten horen we haar denken: ‘In fact I just managed a whole ten minutes there without thinking of you once, I thought, then I turned back to the book. Then I looked up over the top of the open book because it sounded like someone was coming up the stairs. Someone was. It was you.’ Verwilderd haar, haar hele zijn vies van stof en puin, haar oogkassen zwart.

Wat volgt is een gesprek tussen beiden, over van alles, waarin gewoontes naar voren komen, waarin ze literatuur aanhalen, waarin een gedeeld verleden wordt opgedist. Op een gegeven moment denkt de hoofdpersoon, ik moet haar thee aanbieden, en realiseert zich dan dat de partner op de bank een product van haar verbeelding is. Dit maakt echter niet dat het samenzijn met haar partner stopt, het leidt tot een verfrissend inzicht: ‘I could offer a figment of my imagination tea if I wanted.’ De wonderbaarlijke kracht van de verbeelding wordt door Ali Smith ruimschoots geprezen: ‘Oh, the imagination was fantastic: mine didn’t just make up some place you’d been, it even made up words whose meanings I didn’t know – which was exactly what it had been like, to live with you. In fact when I went through and tried to look up that word in the dictionary I couldn’t find a word like it. So the imagination was even more amazing than I’d given it credit for.’

Dat tijdsbeleving niet hoeft samen te vallen met de daadwerkelijk verstreken tijd, voelen we het meest als de emoties het hoogst zijn. Zoals in ‘On time’, wanneer een dierbaar iemand overlijdt. De periode erna kan voelen als tijdloos, een vacuüm, of moeilijk om een tijdskader op te plakken. Duren de dagen lang? Duren ze kort? Soms allebei, op dezelfde dag. Terugdenkend aan wanneer iemand is overleden, klopt de kalendertijd die verstreken is vaak niet met de gevoelsmatige tijd die verstreken is. Zo hoor ik mezelf soms hardop denken: zes jáár, hoe kan het alweer zes jaar geleden zijn. Het is niet te bevatten, ook al is er in die periode ontzettend veel gebeurd, wat maakt dat als ik me daarop focus, ik wel degelijk ervaar én voel dat zes jaar een lange tijd is. Het zijn alleen verschillende perspectieven van waaruit je terugkijkt, met bijbehorend verschillende ervaringen en emoties. Ieders subjectieve en persoonlijke tijd verschilt dus van de door klokken voortgestuwde tijd, en misschien is er binnen die subjectieve tijd soms nog een verschil, afhankelijk van het perspectief dat je inneemt voor die persoonlijke tijdsbeleving. En dit verschil kan onder invloed van heftige emoties groter of kleiner zijn, omdat die emoties onze ervaring van tijd enorm kunnen uitrekken of comprimeren. Zo kan het zijn dat dertig jaar voelt als the blink-of-an-eye, letterlijk een ogenblik.

Nog voordat ze kan proberen te gaan lezen, stuit ze op een probleem. De stoel waarin ze wil gaan lezen, was van haar partner: ‘But it was your chair, this chair, even though we’d bought it on my credit card (and it still wasn’t paid off; how unfair that a chair we saw online and bought on a credit card and had delivered in a van would, could, did, last longer than us). And we’d had that argument about moving it several times and you’d always won that argument.’

Haar partners stoel, waarvan zij vond dat die niet op de juiste plek stond. Niet in staat het juiste licht te vangen, te veel op de tocht, te ver van het bureau bovendien. Is het een loyaliteitsbreuk om de stoel nu te gaan versjouwen? Ze doet het. Met brute kracht en opgestroopte tapijten tot gevolg. Het voelt goed. Na luttele minuten horen we haar denken: ‘In fact I just managed a whole ten minutes there without thinking of you once, I thought, then I turned back to the book. Then I looked up over the top of the open book because it sounded like someone was coming up the stairs. Someone was. It was you.’ Verwilderd haar, haar hele zijn vies van stof en puin, haar oogkassen zwart.

Wat volgt is een gesprek tussen beiden, over van alles, waarin gewoontes naar voren komen, waarin ze literatuur aanhalen, waarin een gedeeld verleden wordt opgedist. Op een gegeven moment denkt de hoofdpersoon, ik moet haar thee aanbieden, en realiseert zich dan dat de partner op de bank een product van haar verbeelding is. Dit maakt echter niet dat het samenzijn met haar partner stopt, het leidt tot een verfrissend inzicht: ‘I could offer a figment of my imagination tea if I wanted.’ De wonderbaarlijke kracht van de verbeelding wordt door Ali Smith ruimschoots geprezen: ‘Oh, the imagination was fantastic: mine didn’t just make up some place you’d been, it even made up words whose meanings I didn’t know – which was exactly what it had been like, to live with you. In fact when I went through and tried to look up that word in the dictionary I couldn’t find a word like it. So the imagination was even more amazing than I’d given it credit for.’

Dat tijdsbeleving niet hoeft samen te vallen met de daadwerkelijk verstreken tijd, voelen we het meest als de emoties het hoogst zijn. Zoals in ‘On time’, wanneer een dierbaar iemand overlijdt. De periode erna kan voelen als tijdloos, een vacuüm, of moeilijk om een tijdskader op te plakken. Duren de dagen lang? Duren ze kort? Soms allebei, op dezelfde dag. Terugdenkend aan wanneer iemand is overleden, klopt de kalendertijd die verstreken is vaak niet met de gevoelsmatige tijd die verstreken is. Zo hoor ik mezelf soms hardop denken: zes jáár, hoe kan het alweer zes jaar geleden zijn. Het is niet te bevatten, ook al is er in die periode ontzettend veel gebeurd, wat maakt dat als ik me daarop focus, ik wel degelijk ervaar én voel dat zes jaar een lange tijd is. Het zijn alleen verschillende perspectieven van waaruit je terugkijkt, met bijbehorend verschillende ervaringen en emoties. Ieders subjectieve en persoonlijke tijd verschilt dus van de door klokken voortgestuwde tijd, en misschien is er binnen die subjectieve tijd soms nog een verschil, afhankelijk van het perspectief dat je inneemt voor die persoonlijke tijdsbeleving. En dit verschil kan onder invloed van heftige emoties groter of kleiner zijn, omdat die emoties onze ervaring van tijd enorm kunnen uitrekken of comprimeren. Zo kan het zijn dat dertig jaar voelt als the blink-of-an-eye, letterlijk een ogenblik.

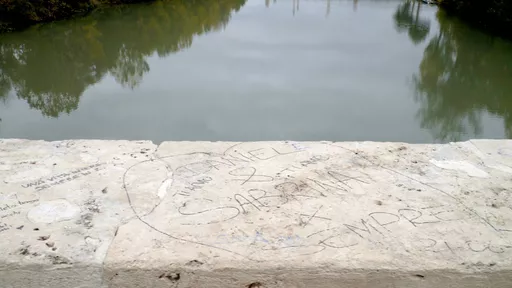

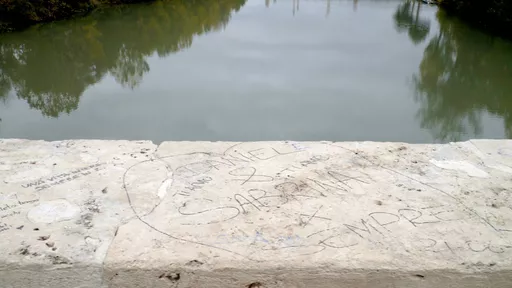

Ik zie een rivier vanaf een brug. Het water is kalm. Stroomt gestaag. Misschien dat dat ‘kabbelend’ heet. De natuurstenen reling van de brug toont namen, soms verbonden met door pijlen doorboorde hartjes, liefdeskreten, beloftes.

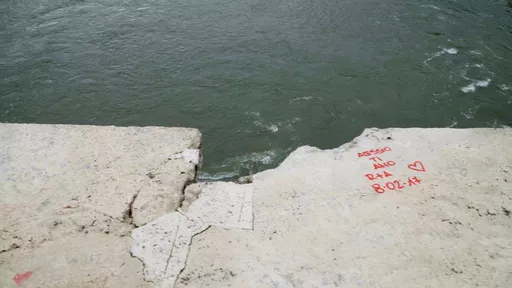

Ik zie opnieuw een rivier. Weer vanaf een brug. Dezelfde rivier, dezelfde brug. Ditmaal is het water onstuimig. Schuimkragen op haar lippen. Het stroomtempo ligt hoog. De natuurstenen reling van de brug toont namen, hartjes, liefdeskreten, beloftes.

De twee rivieren, die zowel niet als wel dezelfde rivier zijn, kan ik in één oogopslag tot me nemen. Ik interpreteer het als een visuele vertaling van Heraclitus’ ‘geen mens kan twee keer in dezelfde rivier stappen’. Het maakt mijn denken lenig: wat een eenvoudige maar ontzettend doeltreffende manier om te verbeelden wat tijd is. Dubbelzinnig, een momentopname, een werkelijkheid op dat moment, nooit hetzelfde, en een oneindige loop.

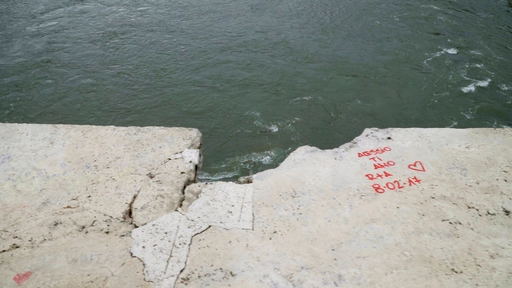

Op de natuurstenen reling: ‘Per sempre.’ ‘Ti amo.’ Sommige boodschappen zijn in het steen gekrast, andere zijn er met een benzinestift opgekalkt. Rood. Zwart. Voor een periode slijtvast – vast niet voor altijd. Ironisch.

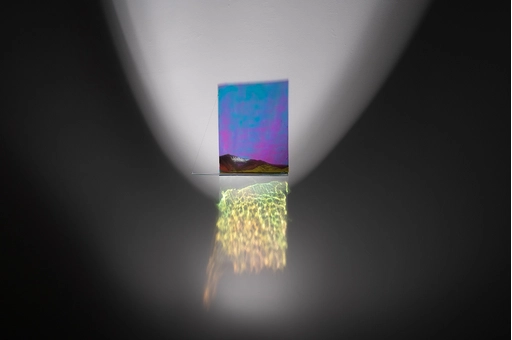

Deze twee rivieren die dezelfde rivier zijn, zag ik in de tentoonstelling Then, now, and then van Marijke van Warmerdam in het Landhuis Oud Amelisweerd, waar ik was op de laatste zaterdag dat deze open was, in november 2022. Ja – ik wilde van meet af aan deze tentoonstelling zien, maar eerder had ik geen tijd. Dat was zo, maar pas nu ik dit schrijf, begrijp ik hoe ironisch ook dát is.

Het werk bestaat uit twee grote schermen naast elkaar, beide vrij in de ruimte geplaatst, waarop de twee shots van dezelfde rivier – maar in verschillende hoedanigheden – te zien zijn. Dit zorgt ervoor dat je beter gaat kijken, zoekt naar de constanten waarin overlap valt te ontdekken en wat er juist anders is. Net als het stromen van water, gaan de films almaar door, in een loop. Het water gaat rond, maar niet op dezelfde gekunstelde manier als de wijzers van de klok.

Even voel ik me licht. We kunnen het verschil in stromen niet op hetzelfde moment meemaken, maar we kunnen het ons wel verbeelden, of voorstellen, als we het hebben gezien, zoals deze kunstervaring maakt dat ik het me kan voorstellen, het geeft me een metaperspectief dat ik niet zelf kan innemen, fysiek, maar wel kan aannemen, geestelijk.

Ik zie opnieuw een rivier. Weer vanaf een brug. Dezelfde rivier, dezelfde brug. Ditmaal is het water onstuimig. Schuimkragen op haar lippen. Het stroomtempo ligt hoog. De natuurstenen reling van de brug toont namen, hartjes, liefdeskreten, beloftes.

De twee rivieren, die zowel niet als wel dezelfde rivier zijn, kan ik in één oogopslag tot me nemen. Ik interpreteer het als een visuele vertaling van Heraclitus’ ‘geen mens kan twee keer in dezelfde rivier stappen’. Het maakt mijn denken lenig: wat een eenvoudige maar ontzettend doeltreffende manier om te verbeelden wat tijd is. Dubbelzinnig, een momentopname, een werkelijkheid op dat moment, nooit hetzelfde, en een oneindige loop.

Op de natuurstenen reling: ‘Per sempre.’ ‘Ti amo.’ Sommige boodschappen zijn in het steen gekrast, andere zijn er met een benzinestift opgekalkt. Rood. Zwart. Voor een periode slijtvast – vast niet voor altijd. Ironisch.

Deze twee rivieren die dezelfde rivier zijn, zag ik in de tentoonstelling Then, now, and then van Marijke van Warmerdam in het Landhuis Oud Amelisweerd, waar ik was op de laatste zaterdag dat deze open was, in november 2022. Ja – ik wilde van meet af aan deze tentoonstelling zien, maar eerder had ik geen tijd. Dat was zo, maar pas nu ik dit schrijf, begrijp ik hoe ironisch ook dát is.

Het werk bestaat uit twee grote schermen naast elkaar, beide vrij in de ruimte geplaatst, waarop de twee shots van dezelfde rivier – maar in verschillende hoedanigheden – te zien zijn. Dit zorgt ervoor dat je beter gaat kijken, zoekt naar de constanten waarin overlap valt te ontdekken en wat er juist anders is. Net als het stromen van water, gaan de films almaar door, in een loop. Het water gaat rond, maar niet op dezelfde gekunstelde manier als de wijzers van de klok.

Even voel ik me licht. We kunnen het verschil in stromen niet op hetzelfde moment meemaken, maar we kunnen het ons wel verbeelden, of voorstellen, als we het hebben gezien, zoals deze kunstervaring maakt dat ik het me kan voorstellen, het geeft me een metaperspectief dat ik niet zelf kan innemen, fysiek, maar wel kan aannemen, geestelijk.

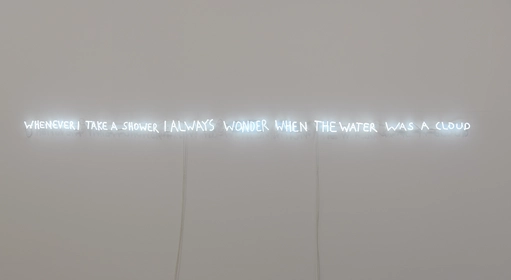

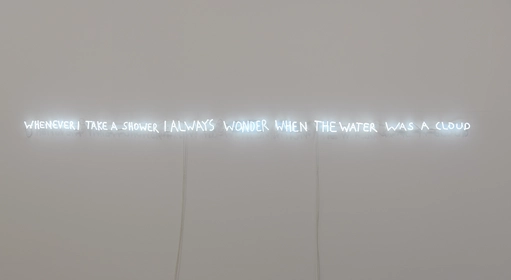

Voordat de mensen klokken maakten, was er al een klok, en die is er nog steeds. Die van de natuur, van de maan, van de zon. Die de getijden beïnvloeden. De link tussen water en tijd is dus een oorspronkelijke. In tegenstelling tot onze kloktijd, die bij uitstek een mal is waarin wij ons allemaal proberen te persen, kent water verschillende staten, het kan transformeren. Water is niet één, het is eventjes iets en in potentie alles. ‘Whenever I take a shower I always wonder when the water was a cloud’, zoals het neonwerk van de kunstenaar David Horvitz treffend verwoordt.

De natuur is onze eerste klok. Het ritme van de zon en maan, lang was er niet meer nodig dan weten wanneer de zon opkwam en wanneer deze onderging: dat waren de productieve uren, de uren waarop er iets te zien was, waarop er gewerkt kon worden. Je wist ongeveer in welke periode van het jaar de oogsttijd was, maar je kon de klok er niet op gelijkzetten: in zo’n gedetailleerde notatie van tijd laat de natuur zich niet dwingen, ze is immers afhankelijk van verschillende variabelen: temperatuur, regenval – om er een paar te noemen.

Op basis van de ritmes van de natuur – dag en nacht, de seizoenen – ontwikkelden mensen klokken. Eerst met behulp van een stokje in de grond waarbij de schaduw een tijdsindicatie was. Zo ontstonden zonnewijzers, waarvan een van de eerste – voor zover we nu weten – uit Egypte komt en dateert van 1500 voor Christus. Ook maakte men gebruik van waterklokken: aan de hand van hoeveel water er was weggelopen kon je aflezen hoeveel tijd er was verstreken, vergelijkbaar met hoe een zandloper werkt. Praktisch, want bij geen zon of met bewolking werkt een zonnewijzer niet. Maar ook onpraktisch, want water kan bevriezen en daarmee ook de tijd.

Met de intrede van de industriële revolutie weet de mens de tijd steeds meer te ‘overwinnen’: de tijd gaat het ritme van de dagen in de werkplaatsen bepalen, hoelang de pauzes zijn van de werknemers, hoeveel zij betaald krijgen (afgeleid van hoeveel tijd ze gewerkt hebben), en uiteindelijk de hoeveelheid vrije tijd die ze hebben. Guido Tonelli schrijft in Tijd: ‘De mensen, ervan dromend Chronos (de naam die de Grieken gebruikten om de lineaire, meetbare tijd mee aan te duiden, red.) te vangen, ontdekken met ontzetting dat ze in werkelijkheid alleen zichzelf tot gevangen hebben gemaakt.’

De kringloop van water is dus een mooie metafoor voor dat wat ontbreekt in onze huidige Westerse en overheersende kapitalistische notie van tijd. Die kringloop resoneert namelijk met het cyclische dat in elk van ons leeft: dat je niet kunt afdwingen in welke staat je bent op welk uur, dat productiviteit in de mate waarop wij het gewend zijn waarschijnlijk veel te veel een geforceerde staat is. Dat maakbaarheid grenzen kent.

De natuur is onze eerste klok. Het ritme van de zon en maan, lang was er niet meer nodig dan weten wanneer de zon opkwam en wanneer deze onderging: dat waren de productieve uren, de uren waarop er iets te zien was, waarop er gewerkt kon worden. Je wist ongeveer in welke periode van het jaar de oogsttijd was, maar je kon de klok er niet op gelijkzetten: in zo’n gedetailleerde notatie van tijd laat de natuur zich niet dwingen, ze is immers afhankelijk van verschillende variabelen: temperatuur, regenval – om er een paar te noemen.

Op basis van de ritmes van de natuur – dag en nacht, de seizoenen – ontwikkelden mensen klokken. Eerst met behulp van een stokje in de grond waarbij de schaduw een tijdsindicatie was. Zo ontstonden zonnewijzers, waarvan een van de eerste – voor zover we nu weten – uit Egypte komt en dateert van 1500 voor Christus. Ook maakte men gebruik van waterklokken: aan de hand van hoeveel water er was weggelopen kon je aflezen hoeveel tijd er was verstreken, vergelijkbaar met hoe een zandloper werkt. Praktisch, want bij geen zon of met bewolking werkt een zonnewijzer niet. Maar ook onpraktisch, want water kan bevriezen en daarmee ook de tijd.

Met de intrede van de industriële revolutie weet de mens de tijd steeds meer te ‘overwinnen’: de tijd gaat het ritme van de dagen in de werkplaatsen bepalen, hoelang de pauzes zijn van de werknemers, hoeveel zij betaald krijgen (afgeleid van hoeveel tijd ze gewerkt hebben), en uiteindelijk de hoeveelheid vrije tijd die ze hebben. Guido Tonelli schrijft in Tijd: ‘De mensen, ervan dromend Chronos (de naam die de Grieken gebruikten om de lineaire, meetbare tijd mee aan te duiden, red.) te vangen, ontdekken met ontzetting dat ze in werkelijkheid alleen zichzelf tot gevangen hebben gemaakt.’

De kringloop van water is dus een mooie metafoor voor dat wat ontbreekt in onze huidige Westerse en overheersende kapitalistische notie van tijd. Die kringloop resoneert namelijk met het cyclische dat in elk van ons leeft: dat je niet kunt afdwingen in welke staat je bent op welk uur, dat productiviteit in de mate waarop wij het gewend zijn waarschijnlijk veel te veel een geforceerde staat is. Dat maakbaarheid grenzen kent.

Een aantal jaar terug was ik in Berlijn en hingen er verspreid door de stad posters met de tekst ‘Nobody owns the beach’. Ik vond het fascinerende affiches, vanwege de tekst en het feit dat ze louter uit typografie bestonden, maar vooral omdat ze doorgaans in de buurt hingen van posters die duidelijk probeerden me iets aan te smeren: een haarproduct, een nieuw type bier, een dating-app.

Mijn eerste gedachte bij ‘Nobody owns the beach’ was: natuurlijk bezit niemand het strand, stel je voor. Maar toen ik er vervolgens over na ging denken durfde ik niet te zeggen hoeveel natuur er nog echt van ‘zichzelf’ is. Het conceptualiseren (cultiveren) van natuur voor kapitalistisch gewin is onze status quo. En anders, of misschien zelfs in het verlengde daarvan, is natuur er voor onze recreatie (als invulling van de, door datzelfde kapitalisme grootgemaakte, ‘vrije tijd’). Daarmee is de natuur veroverd, heeft het nut, en gebruiken we haar in plaats van naar haar – en haar ritmes – te luisteren.

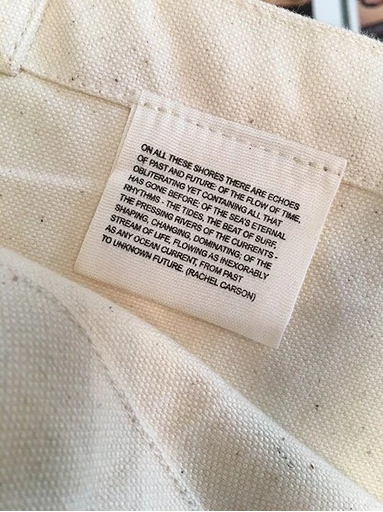

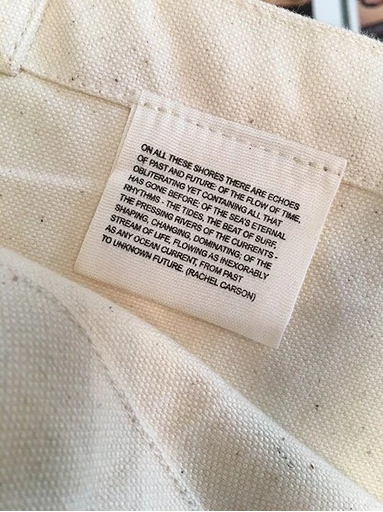

Wat ik destijds niet wist, maar nu wel, is dat deze posters ook van de hand zijn David Horvitz, en dat hij een totebag ontwierp met dezelfde tekst. Totebag, het verzetstasje dat hip werd, dat het werk een enigszins ironisch commentaar op het kapitalisme maakt. Op het waslabel van de totebag, aan de binnenzijde, staat een tekstfragment van niemand minder dan Rachel Carson: ‘On all these shores there are echoes of past and future: of the flow of time, obliterating yet containing all that has gone before; of the sea’s eternal rhythms – the tides, the beat of surf shaping, changing, dominating; of the stream of life, flowing as inexorably as any ocean current, from past to unknown future.’

Tijd en transformatie komen vaak aan bod in Horvitz’ werken. Zijn Nautical Dusk (2013) bestaat uit een bel met daarnaast een bordje met een toelichting:

Notice

For the current exhibition [Title] from [Date] until [Date], the gallery’s normal closing time of 6 pm will change to the time of each day’s nautical dusk.

Today’s closing time will be at …….

Ik probeer me voor te stellen wat het met me zou doen als ik dit werk zou tegenkomen in een tentoonstellingsruimte. Vaak denk ik: ah, als ik om 15:00 uur bij die kunstruimte ben, dan heb ik nog 2 uur de tijd om alles te bekijken, want ze sluiten om 17:00 uur. Als de ruimte veel eerder zou sluiten omdat de nautische schemering is aangebroken, zou ik ineens minder tijd hebben om alles te bekijken. Het werk is als het ware een interventie: zet alles op scherp, is een adequate manier om invoelbaar te maken hoezeer de tijd ons in haar greep heeft en waar het ten koste van gaat, wat het kost.

Mijn eerste gedachte bij ‘Nobody owns the beach’ was: natuurlijk bezit niemand het strand, stel je voor. Maar toen ik er vervolgens over na ging denken durfde ik niet te zeggen hoeveel natuur er nog echt van ‘zichzelf’ is. Het conceptualiseren (cultiveren) van natuur voor kapitalistisch gewin is onze status quo. En anders, of misschien zelfs in het verlengde daarvan, is natuur er voor onze recreatie (als invulling van de, door datzelfde kapitalisme grootgemaakte, ‘vrije tijd’). Daarmee is de natuur veroverd, heeft het nut, en gebruiken we haar in plaats van naar haar – en haar ritmes – te luisteren.

Wat ik destijds niet wist, maar nu wel, is dat deze posters ook van de hand zijn David Horvitz, en dat hij een totebag ontwierp met dezelfde tekst. Totebag, het verzetstasje dat hip werd, dat het werk een enigszins ironisch commentaar op het kapitalisme maakt. Op het waslabel van de totebag, aan de binnenzijde, staat een tekstfragment van niemand minder dan Rachel Carson: ‘On all these shores there are echoes of past and future: of the flow of time, obliterating yet containing all that has gone before; of the sea’s eternal rhythms – the tides, the beat of surf shaping, changing, dominating; of the stream of life, flowing as inexorably as any ocean current, from past to unknown future.’

Tijd en transformatie komen vaak aan bod in Horvitz’ werken. Zijn Nautical Dusk (2013) bestaat uit een bel met daarnaast een bordje met een toelichting:

Notice

For the current exhibition [Title] from [Date] until [Date], the gallery’s normal closing time of 6 pm will change to the time of each day’s nautical dusk.

Today’s closing time will be at …….

Ik probeer me voor te stellen wat het met me zou doen als ik dit werk zou tegenkomen in een tentoonstellingsruimte. Vaak denk ik: ah, als ik om 15:00 uur bij die kunstruimte ben, dan heb ik nog 2 uur de tijd om alles te bekijken, want ze sluiten om 17:00 uur. Als de ruimte veel eerder zou sluiten omdat de nautische schemering is aangebroken, zou ik ineens minder tijd hebben om alles te bekijken. Het werk is als het ware een interventie: zet alles op scherp, is een adequate manier om invoelbaar te maken hoezeer de tijd ons in haar greep heeft en waar het ten koste van gaat, wat het kost.

Horvitz wil de plek, de situatie, koppelen aan ons heersende idee van tijd en aan iets dat er altijd is en een eigen ritme in zich draagt – de natuur. In de tentoonstellingsruimte voelbaar maken hoezeer kunst deel uitmaakt van het kapitalistische systeem met zo weinig als een bel, een tekst én een geforceerd veranderende sluitingstijd, bijvoorbeeld.

Maar ook met het verspreiden van de ‘Nobody owns the beach’-posters wordt de locatie waar ze hangen (grootstedelijk) gekoppeld aan een plek die daar ver van verwijderd is of vanaf staat (strand, natuur). Waarmee in een klap duidelijk wordt, ik zou bijna willen schrijven ‘voelbaar’, hoe die twee in ritme en tempo verschillen. Onnatuurlijk versus natuurlijk. Horvitz zelf zegt: ‘A lot of my work is about reminding yourself that you are somewhere unique – in a spatial sense and a temporal sense. Imagine what it was like before time zones, when places had their own times. What time is it? Where exactly are we right now?’ En over de andere ritmes die ons bestaan bepalen: ‘To me, it is more interesting when something happens that you don’t expect. I really despise keeping a schedule because for me that ruins a day. You already define what you are doing at a certain time and place, and that day is no longer open for something unexpected to happen. A few years ago I did two connected shows at Jan Mot in Brussels and Dawid Radziszewski in Warsaw. The shows opened the day my friend Jenny gave birth to her daughter, so no one knew exactly when the opening would be. I wanted it to be unknown, to complicate the gallery’s calendrical system with the biological (and lunar?) rhythms of my friend’s body. I’ve always been amused when Brooklyn Botanical Gardens would have their Sakura festival and none of the cherry trees would be in bloom yet, or the peak blooms would be over. The gardens would have to schedule it a year in advance for various reasons, but a tree will bloom when it wants to bloom. In Japan, the moments the trees blossom is the moment you celebrate Sakura. You are on the tree’s schedule – it doesn’t follow your Google calendar.’

Dat we zelfs denken dat we onze hang naar maakbaarheid kunnen projecteren op de ritmes van de natuur, is vandaag de dag meer dan duidelijk. Alle tekenen die we maar kunnen krijgen over dat het niet de goede kant op gaat met de planeet en we te weinig doen om de klimaatcrisis te bestrijden, blijken door velen nog steeds prima genegeerd te kunnen worden. De centrale positie die we onszelf als mens hebben toegedicht is zo alomtegenwoordig dat we denken dat we ook dit wel oplossen zonder nu te handelen. Het gegeven dat ons eigen leven afhankelijk is van al het leven om ons heen, lijkt nauwelijks door te dringen.

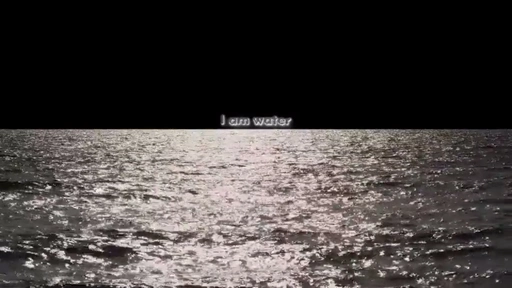

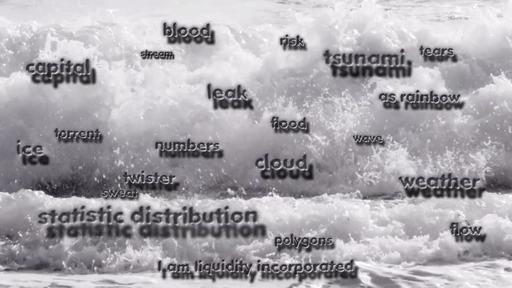

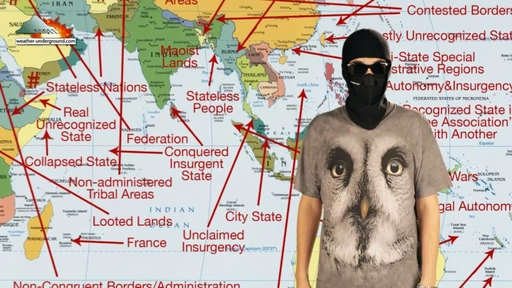

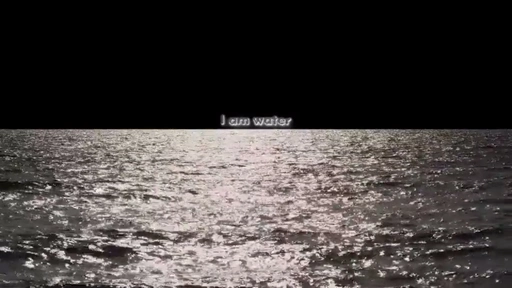

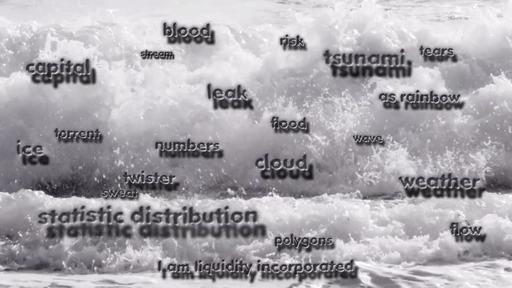

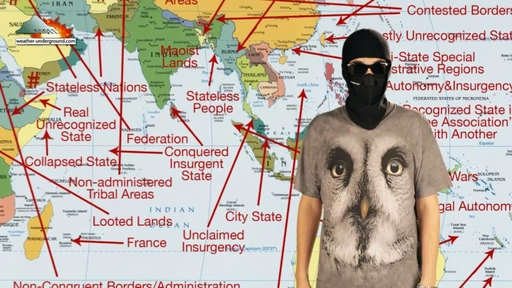

Deze ver doorgevoerde kapitalisering van natuur in relatie tot onze agenda’s – zowel in de letterlijke als meer metaforische betekenis – wordt nog verder uitvergroot in het hallucinante videowerk Liquidity Inc. van de kunstenaar Hito Steyerl. Steyerl legt de nadruk op de veelvormigheid van water, de kringloop, de verschillende fases die iets doorloopt, de verschillende versies die iets kan zijn, de oneindige combinaties die gemaakt kunnen worden tussen concepten die aanvankelijk niks met elkaar te maken lijken te hebben. In de eerste minuten van Liquidity Inc. horen we een voice-over die spreekt vanuit het perspectief van het water. Terwijl ‘I am liquidity incorporated’ klinkt, verschijnen er in beeld woorden als ‘as rainbow’, ‘torrent’, ‘cloud’, en later ‘leak’, ‘flood’, ‘wave’, ‘tsunami’, ‘tears’, ‘sweat’, ‘ice’, ‘flow’, ‘weather’, ‘stream’, ‘twister’. In deze gedaantes kunnen we ons water goed voorstellen.

Dan volgen er meer raadselachtige begrippen: ‘polygons’, ‘numbers’, ‘capital’, ‘statistic distribution’, ‘risk’. Maar wellicht toch niet zo raadselachtig aangezien we al eerder hebben geconstateerd dat water en tijd met elkaar verbonden zijn. En tijd is geld. Liquidity Inc. is, zoals alle werken van Steyerl, bizar, stilistisch veelvoudig, over de top, ongrijpbaar. Het is een complex visueel essay waarin je als kijker heen en weer geslingerd wordt. Aan welke kant sta je eigenlijk? En wat is het moreel juiste standpunt?

Maar ook met het verspreiden van de ‘Nobody owns the beach’-posters wordt de locatie waar ze hangen (grootstedelijk) gekoppeld aan een plek die daar ver van verwijderd is of vanaf staat (strand, natuur). Waarmee in een klap duidelijk wordt, ik zou bijna willen schrijven ‘voelbaar’, hoe die twee in ritme en tempo verschillen. Onnatuurlijk versus natuurlijk. Horvitz zelf zegt: ‘A lot of my work is about reminding yourself that you are somewhere unique – in a spatial sense and a temporal sense. Imagine what it was like before time zones, when places had their own times. What time is it? Where exactly are we right now?’ En over de andere ritmes die ons bestaan bepalen: ‘To me, it is more interesting when something happens that you don’t expect. I really despise keeping a schedule because for me that ruins a day. You already define what you are doing at a certain time and place, and that day is no longer open for something unexpected to happen. A few years ago I did two connected shows at Jan Mot in Brussels and Dawid Radziszewski in Warsaw. The shows opened the day my friend Jenny gave birth to her daughter, so no one knew exactly when the opening would be. I wanted it to be unknown, to complicate the gallery’s calendrical system with the biological (and lunar?) rhythms of my friend’s body. I’ve always been amused when Brooklyn Botanical Gardens would have their Sakura festival and none of the cherry trees would be in bloom yet, or the peak blooms would be over. The gardens would have to schedule it a year in advance for various reasons, but a tree will bloom when it wants to bloom. In Japan, the moments the trees blossom is the moment you celebrate Sakura. You are on the tree’s schedule – it doesn’t follow your Google calendar.’

Dat we zelfs denken dat we onze hang naar maakbaarheid kunnen projecteren op de ritmes van de natuur, is vandaag de dag meer dan duidelijk. Alle tekenen die we maar kunnen krijgen over dat het niet de goede kant op gaat met de planeet en we te weinig doen om de klimaatcrisis te bestrijden, blijken door velen nog steeds prima genegeerd te kunnen worden. De centrale positie die we onszelf als mens hebben toegedicht is zo alomtegenwoordig dat we denken dat we ook dit wel oplossen zonder nu te handelen. Het gegeven dat ons eigen leven afhankelijk is van al het leven om ons heen, lijkt nauwelijks door te dringen.

Deze ver doorgevoerde kapitalisering van natuur in relatie tot onze agenda’s – zowel in de letterlijke als meer metaforische betekenis – wordt nog verder uitvergroot in het hallucinante videowerk Liquidity Inc. van de kunstenaar Hito Steyerl. Steyerl legt de nadruk op de veelvormigheid van water, de kringloop, de verschillende fases die iets doorloopt, de verschillende versies die iets kan zijn, de oneindige combinaties die gemaakt kunnen worden tussen concepten die aanvankelijk niks met elkaar te maken lijken te hebben. In de eerste minuten van Liquidity Inc. horen we een voice-over die spreekt vanuit het perspectief van het water. Terwijl ‘I am liquidity incorporated’ klinkt, verschijnen er in beeld woorden als ‘as rainbow’, ‘torrent’, ‘cloud’, en later ‘leak’, ‘flood’, ‘wave’, ‘tsunami’, ‘tears’, ‘sweat’, ‘ice’, ‘flow’, ‘weather’, ‘stream’, ‘twister’. In deze gedaantes kunnen we ons water goed voorstellen.

Dan volgen er meer raadselachtige begrippen: ‘polygons’, ‘numbers’, ‘capital’, ‘statistic distribution’, ‘risk’. Maar wellicht toch niet zo raadselachtig aangezien we al eerder hebben geconstateerd dat water en tijd met elkaar verbonden zijn. En tijd is geld. Liquidity Inc. is, zoals alle werken van Steyerl, bizar, stilistisch veelvoudig, over de top, ongrijpbaar. Het is een complex visueel essay waarin je als kijker heen en weer geslingerd wordt. Aan welke kant sta je eigenlijk? En wat is het moreel juiste standpunt?

‘Empty your mind. Be formless. Shapeless. Like water. You put water into a cup, it becomes the cup. You put water into a bottle, it becomes the bottle. You put it in a teapot, it becomes the teapot. Water can flow, or it can crash. Be water, my friend’, horen we de voice-over zeggen. Het klinkt als een bezwering. Het klinkt ook sekte-achtig. Is flexibel en buigzaam zijn iets goeds? Of is het precies die maakbaarheid die mooi lijkt, maar ruggengraatloos is? Precies die ruggengraatloosheid waar vervuilende industrie, overheden en andere partijen bij gebaat zijn omdat het ervoor zorgt dat we braaf rond blijven gaan in de tredmolen? Steyerl verweeft die maakbaarheid met de betekenis van liquiditeit – vloeibaarheid en vermogend zijn –: ‘When you have liquidity, you’re in control.’

Plooibaarheid en flexibiliteit zijn gevaarlijk verwant, maar zijn zelden hetzelfde. Onder flexibel zijn valt het willen aanpassen van je standpunt omdat bij nader inzien blijkt dat je het toch niet bij het juiste eind had, of dat nieuwe inzichten ervoor zorgen dat je van richting wilt veranderen. Plooibaarheid is het makkelijk in de maat mee kunnen lopen. Met alle winden meewaaien. Laat het nu juist aan Steyerl over om dat meewaaien om te keren en een treffende bespiegeling te bieden op wat van wie is in deze wereld, en wie zich kan veroorloven flexibel te zijn. In de vorm van een weerbericht kondigt Liquidity Inc. aan dat er handelswinden waaien, mensen terugwaaien naar hun huizen, producten terugwaaien naar hun fabrieken, fabrieken weer terugwaaien naar hun landen, landen terug naar hun veronderstelde oorsprong. ‘Blowing people back into their past.’ Het is hoogintelligente systeemkritiek in een lyrisch jasje. ‘Weather is time.’ ‘Weather is money.’ ‘Weather is water.’ Het was zelden zo accuraat als nu.

Plooibaarheid en flexibiliteit zijn gevaarlijk verwant, maar zijn zelden hetzelfde. Onder flexibel zijn valt het willen aanpassen van je standpunt omdat bij nader inzien blijkt dat je het toch niet bij het juiste eind had, of dat nieuwe inzichten ervoor zorgen dat je van richting wilt veranderen. Plooibaarheid is het makkelijk in de maat mee kunnen lopen. Met alle winden meewaaien. Laat het nu juist aan Steyerl over om dat meewaaien om te keren en een treffende bespiegeling te bieden op wat van wie is in deze wereld, en wie zich kan veroorloven flexibel te zijn. In de vorm van een weerbericht kondigt Liquidity Inc. aan dat er handelswinden waaien, mensen terugwaaien naar hun huizen, producten terugwaaien naar hun fabrieken, fabrieken weer terugwaaien naar hun landen, landen terug naar hun veronderstelde oorsprong. ‘Blowing people back into their past.’ Het is hoogintelligente systeemkritiek in een lyrisch jasje. ‘Weather is time.’ ‘Weather is money.’ ‘Weather is water.’ Het was zelden zo accuraat als nu.

Ik denk terug aan de woorden op de reling van de brug in het werk van Marijke van Warmerdam: per sempre. De Grieken geloofden dat de oceaan een eindeloze stroom was die eeuwig over de rand van de wereld vloeide en daarmee het einde van de bekende wereld markeerde. Daarachter het ongekende, het onbekende. Laat de mythe een metafoor zijn: de natuur weet nog zoveel dat wij nog niet ontdekt of ontrafeld hebben. Het ‘voor altijd’ (per sempre) dat betuigd wordt met het opschrijven van twee namen verbonden door een hartje met een pijl erdoorheen op de leuning van de brug waaronder water stroomt, is nog het meest van toepassing op precies dat: het water. Het zal er altijd zijn, alleen niet waar, wanneer en op welke manier wij willen. Het water zal te hoog zijn op plekken die zich dat niet kunnen permitteren, en te laag of afwezig op weer andere plekken – met alle gevolgen van dien.

We kunnen niet twee keer in dezelfde rivier stappen, het moment is niet zo maakbaar als we denken. In ‘On time’ laat Smith haar hoofdpersonage denken: ‘You can’t step into the same story twice – or maybe it’s that stories, books, art can’t step into the same person twice, maybe it’s that they allow for our mutability, are ready for us at all times, and maybe it’s this adaptability, regardless of time, that makes them art, because real art (as opposed to more transient art, which is real too, just for less time) will hold us at all our different ages like it held all the people before us and will hold all the people after us, in an elasticity and with a generosity that allow for all our comings and goings.’

Het lijkt mij een pleidooi om van de kunst – in brede zin – ons alternatieve ‘meetinstrument’ te maken, precies in de betekenis die Smith eraan toedicht: wanneer we terugkeren naar de werken die we kennen, ervaren we wie we zijn ten opzichte van onze eerste ervaring met dat werk. Die ontwikkeling is niet lineair, maar gebaseerd op verwijdering en toenadering, zoals alles in het leven daarop gebaseerd is. De maan, de zon: dichterbij en weer verder weg, eb, vloed, donker, licht. Het maakt nederig en weerbaar: terugkeren naar iets dat je dacht te kennen, en te ervaren dat het veranderd is, dat jij veranderd bent, maar andersom ook, terugkeren naar iets en nog steeds geraakt worden door dat wat je eerder zo herkende. Dat vaak genoeg doen, is zacht verzet, een manier om de idee te blijven voeden van een andere tijd dan alleen de kapitalistische notie ervan: jezelf bewust te blijven maken dat échte groei niet alleen vooruitgaat, maar veel vaker betekent dat je een stap terugzet, om van perspectief te kunnen wisselen, om flexibel te blijven, in plaats van plooibaar te worden.

We kunnen niet twee keer in dezelfde rivier stappen, het moment is niet zo maakbaar als we denken. In ‘On time’ laat Smith haar hoofdpersonage denken: ‘You can’t step into the same story twice – or maybe it’s that stories, books, art can’t step into the same person twice, maybe it’s that they allow for our mutability, are ready for us at all times, and maybe it’s this adaptability, regardless of time, that makes them art, because real art (as opposed to more transient art, which is real too, just for less time) will hold us at all our different ages like it held all the people before us and will hold all the people after us, in an elasticity and with a generosity that allow for all our comings and goings.’

Het lijkt mij een pleidooi om van de kunst – in brede zin – ons alternatieve ‘meetinstrument’ te maken, precies in de betekenis die Smith eraan toedicht: wanneer we terugkeren naar de werken die we kennen, ervaren we wie we zijn ten opzichte van onze eerste ervaring met dat werk. Die ontwikkeling is niet lineair, maar gebaseerd op verwijdering en toenadering, zoals alles in het leven daarop gebaseerd is. De maan, de zon: dichterbij en weer verder weg, eb, vloed, donker, licht. Het maakt nederig en weerbaar: terugkeren naar iets dat je dacht te kennen, en te ervaren dat het veranderd is, dat jij veranderd bent, maar andersom ook, terugkeren naar iets en nog steeds geraakt worden door dat wat je eerder zo herkende. Dat vaak genoeg doen, is zacht verzet, een manier om de idee te blijven voeden van een andere tijd dan alleen de kapitalistische notie ervan: jezelf bewust te blijven maken dat échte groei niet alleen vooruitgaat, maar veel vaker betekent dat je een stap terugzet, om van perspectief te kunnen wisselen, om flexibel te blijven, in plaats van plooibaar te worden.

Literatuur

Carson, R. (2022). De zee. Athenaeum – Polak & Van Gennep.

Norton, M. (2017). David Horvitz in conversation with Margot Norton. CURA. Magazine. curamagazine.com/digital/david-horvitz/

Smith, A. (2012). Artful. Penguin Random House UK.

Tonelli, G. (2022). Tijd. Een reis van vroeger naar later. De Bezige Bij.

______________________________________________

Norton, M. (2017). David Horvitz in conversation with Margot Norton. CURA. Magazine. curamagazine.com/digital/david-horvitz/

Smith, A. (2012). Artful. Penguin Random House UK.

Tonelli, G. (2022). Tijd. Een reis van vroeger naar later. De Bezige Bij.

______________________________________________

The sea as metronome: estrangement and reconciliation as experiences of time

Essay by Laure van den Hout

translation by MM Garr

Can we make time, time for not-knowing as a productive force? How do we ensure that making time does not also increasingly fall prey to the laws of capitalisation? Can time be a creative tool? In the series TIJD, ArtEZ Studium Generale and Mister Motley take a closer look at this.

For this series, Laure van den Hout wrote the opening essay The sea as metronome in which, using nature as the first clock, she discusses an experience of time shaped by rapprochement and separation. Think of the moon and the sun - closer and further away again - of dark and light, ebb and flow. Using water and the different forms in which it presents itself, Van den Hout shows that you cannot force what state you are in at what hour, that productivity to the extent we are used to it is probably far too much of a forced state. That social engineering and makeable time have limits.

For this series, Laure van den Hout wrote the opening essay The sea as metronome in which, using nature as the first clock, she discusses an experience of time shaped by rapprochement and separation. Think of the moon and the sun - closer and further away again - of dark and light, ebb and flow. Using water and the different forms in which it presents itself, Van den Hout shows that you cannot force what state you are in at what hour, that productivity to the extent we are used to it is probably far too much of a forced state. That social engineering and makeable time have limits.

In her extraordinary book The Sea Around Us, marine biologist Rachel Carson writes on the fascinating depths from which we humans came. Though the book was first published in 1951, it remains surprisingly current. Her holistic view of nature, and the predominantly negative influence humans have on it, come out in every word. One passage in particular has stuck with me, in which Carson cites a private encounter with the sea as the moment when a person realizes they are only part of a much larger whole, a whole where their illusion of social engineering is no more than pretense:

"He [i.e. humans] cannot control or change the ocean as, in his brief tenancy of earth, he has subdued and plundered the continents. In the artificial world of his cities and towns, he often forgets the true nature of his planet and the long vistas of its history, in which the existence of the race of men has occupied a mere moment of time. The sense of all these things comes to him most clearly in the course of a long ocean voyage, when he watches day after day the receding rim of the horizon, ridged and furrowed by waves; when at night he becomes aware of the earth's rotation as the stars pass overhead; or when, alone in this world of water and sky, he feels the loneliness of his earth in space. And then, as never on land, he knows the truth that his world is a water world, a planet dominated by its covering mantle of ocean, in which the continents are but transient intrusions of land above the surface of the allencircling sea."

Carson writes wonderfully about the most unimaginable things. About fur seals with bones in their stomachs from a species of fish that humans have never seen alive. About why warm-blooded mammals like baleen whales seem to be immune to caisson disease ("the bends" or decompression sickness), even though they ostensibly make vertical dives into the depths and return to the surface "almost immediately". She attempts explanation, but more so tries to celebrate wonder, the wonder that leads some to study the reason behind it, but also the wonder that is so real in and of itself.

It is wonder that softens us to our surroundings, makes us look harder, makes us aware of how necessary to our own lives all life around us is. Which, in short, makes us humble. In this wonder, Carson returns again and again to time as a guiding element. First, in the opening chapter "I Mother Sea", when she describes how the seas were created, how the now-natural rhythms developed, how the sun and moon play an important role in them, just as they also help determine which organism lives where.

But also more subtle, and more conceptual: how there are depths to which we can hardly, if at all, descend, places where we assume nothing lives (here, of course, a parallel can be drawn with the depths in the other direction: space). Our imagination of what is feasible takes our own conditions of existence as a frame of reference – logical, of course, but also frequently wrong. At the bottom of the deep sea, devoid of light, live worms.

"He [i.e. humans] cannot control or change the ocean as, in his brief tenancy of earth, he has subdued and plundered the continents. In the artificial world of his cities and towns, he often forgets the true nature of his planet and the long vistas of its history, in which the existence of the race of men has occupied a mere moment of time. The sense of all these things comes to him most clearly in the course of a long ocean voyage, when he watches day after day the receding rim of the horizon, ridged and furrowed by waves; when at night he becomes aware of the earth's rotation as the stars pass overhead; or when, alone in this world of water and sky, he feels the loneliness of his earth in space. And then, as never on land, he knows the truth that his world is a water world, a planet dominated by its covering mantle of ocean, in which the continents are but transient intrusions of land above the surface of the allencircling sea."

Carson writes wonderfully about the most unimaginable things. About fur seals with bones in their stomachs from a species of fish that humans have never seen alive. About why warm-blooded mammals like baleen whales seem to be immune to caisson disease ("the bends" or decompression sickness), even though they ostensibly make vertical dives into the depths and return to the surface "almost immediately". She attempts explanation, but more so tries to celebrate wonder, the wonder that leads some to study the reason behind it, but also the wonder that is so real in and of itself.

It is wonder that softens us to our surroundings, makes us look harder, makes us aware of how necessary to our own lives all life around us is. Which, in short, makes us humble. In this wonder, Carson returns again and again to time as a guiding element. First, in the opening chapter "I Mother Sea", when she describes how the seas were created, how the now-natural rhythms developed, how the sun and moon play an important role in them, just as they also help determine which organism lives where.

But also more subtle, and more conceptual: how there are depths to which we can hardly, if at all, descend, places where we assume nothing lives (here, of course, a parallel can be drawn with the depths in the other direction: space). Our imagination of what is feasible takes our own conditions of existence as a frame of reference – logical, of course, but also frequently wrong. At the bottom of the deep sea, devoid of light, live worms.

In "On time" in her book Artful, Ali Smith writes about someone whose partner has passed away. She walks through her home, the home she shared with her partner, sees how their books are intermingled on the shelves ("the most faithful act of all, mix our separate books into one library"), picks one out. It is Dickens' Oliver Twist. She hasn't been able to read since the loss – it has been a year and a day. And she thinks back to when she last read the book now in her hands: "I'd not read Oliver Twist since, oh god, when? way before we even first knew each other, I'd had to, for university, so that made it thirty years. That gave me a shake. A twelvemonth and a day can arguably be called short, but thirty years? How could thirty years be the blink-of-an-eye it felt? It was the difference between black and white footage of the Second World War and David Bowie on Top of the Pops singing Life on Mars; it was the size of a grown woman with four children, one of them nearly old enough, if the woman started very early, to be doing A-levels. They definitely weren't called A-levels anymore."

There's a dilemma, though, that she must face before she is to read again. The chair she wants to start reading in belonged to her partner: "But it was your chair, this chair, even though we'd bought it on my credit card (and it still wasn't paid off; how unfair that a chair we saw online and bought on a credit card and had delivered in a van would, could, did, last longer than us). And we'd had that argument about moving it several times and you'd always won that argument."

Her partner's chair, which she didn't think was in the right spot. Not able to catch the right light, too much of a draft, too far from the desk in any case. Would moving it now be an act of disloyalty? She does it. With brute force and rolled-up rugs as a result. It feels good. After a few minutes, we hear her thinking, "In fact I just managed a whole ten minutes there without thinking of you once, I thought, then I turned back to the book. Then I looked up over the top of the open book because it sounded like someone was coming up the stairs. Someone was. It was you." Disheveled hair, covered in dust and debris, her eye sockets black.

A conversation between them follows, about all manner of things: they bring up habits, they cite literature, tell stories of their shared past. At one point, the protagonist thinks, I should offer her tea, and then realizes that the partner on the couch is a figment of her imagination. This does not, however, make this being with her partner stop; it leads to a refreshing insight: "I could offer a figment of my imagination tea if I wanted." Ali Smith has lavish praise for the wonderous power of imagination: "Oh, the imagination was fantastic: mine didn't just make up some place you'd been, it even made up words whose meanings I didn't know – which was exactly what it had been like, to live with you. In fact when I went through and tried to look up that word in the dictionary I couldn't find a word like it. So the imagination was even more amazing than I'd given it credit for."

That our perception of time need not coincide with actual elapsed time, we feel most when emotions are at their highest. As in "On Time", when a loved one dies. The period after can feel timeless, like a vacuum, or hard to put a timeframe around. Are the days endless? Do they fly by? Sometimes both, on the same day. Thinking back to when someone died, the calendar time that passed often does not match the felt time that passed. For example, I sometimes hear myself thinking out loud: six years, how can it have been six years already. It is incomprehensible, even though a lot has happened in that time, which means that when I do focus in on it, I really feel the length of those six years. It's just different perspectives to look back from, with their corresponding experiences and emotions. Everyone's subjective and personal time differs, therefore, from the time that is propelled by clocks, and perhaps within that subjective time there is occasionally another dissimilarity, depending on the perspective you take for that personal experience of time. And under the influence of intense emotions, this difference may be larger or smaller, because those emotions can considerably stretch or compress our experience of time. So thirty years can feel like an instant, literally a blink of an eye.

There's a dilemma, though, that she must face before she is to read again. The chair she wants to start reading in belonged to her partner: "But it was your chair, this chair, even though we'd bought it on my credit card (and it still wasn't paid off; how unfair that a chair we saw online and bought on a credit card and had delivered in a van would, could, did, last longer than us). And we'd had that argument about moving it several times and you'd always won that argument."

Her partner's chair, which she didn't think was in the right spot. Not able to catch the right light, too much of a draft, too far from the desk in any case. Would moving it now be an act of disloyalty? She does it. With brute force and rolled-up rugs as a result. It feels good. After a few minutes, we hear her thinking, "In fact I just managed a whole ten minutes there without thinking of you once, I thought, then I turned back to the book. Then I looked up over the top of the open book because it sounded like someone was coming up the stairs. Someone was. It was you." Disheveled hair, covered in dust and debris, her eye sockets black.

A conversation between them follows, about all manner of things: they bring up habits, they cite literature, tell stories of their shared past. At one point, the protagonist thinks, I should offer her tea, and then realizes that the partner on the couch is a figment of her imagination. This does not, however, make this being with her partner stop; it leads to a refreshing insight: "I could offer a figment of my imagination tea if I wanted." Ali Smith has lavish praise for the wonderous power of imagination: "Oh, the imagination was fantastic: mine didn't just make up some place you'd been, it even made up words whose meanings I didn't know – which was exactly what it had been like, to live with you. In fact when I went through and tried to look up that word in the dictionary I couldn't find a word like it. So the imagination was even more amazing than I'd given it credit for."

That our perception of time need not coincide with actual elapsed time, we feel most when emotions are at their highest. As in "On Time", when a loved one dies. The period after can feel timeless, like a vacuum, or hard to put a timeframe around. Are the days endless? Do they fly by? Sometimes both, on the same day. Thinking back to when someone died, the calendar time that passed often does not match the felt time that passed. For example, I sometimes hear myself thinking out loud: six years, how can it have been six years already. It is incomprehensible, even though a lot has happened in that time, which means that when I do focus in on it, I really feel the length of those six years. It's just different perspectives to look back from, with their corresponding experiences and emotions. Everyone's subjective and personal time differs, therefore, from the time that is propelled by clocks, and perhaps within that subjective time there is occasionally another dissimilarity, depending on the perspective you take for that personal experience of time. And under the influence of intense emotions, this difference may be larger or smaller, because those emotions can considerably stretch or compress our experience of time. So thirty years can feel like an instant, literally a blink of an eye.

From a bridge, I look out on a river. The water is calm. Steady flow. Maybe that's what's called "trickling". The natural stone sides of the bridge display names, sometimes intersecting with hearts pierced by arrows, professions of love, promises.

Again I see a river. Again from a bridge. The same river, the same bridge. This time the water is rough. Foaming at the mouth. A fast current. The natural stone sides of the bridge display names, hearts, professions of love, promises.

I can take in these two rivers, that are and are not the same river, in a single view. I see this as a visual translation of Heraclitus' "no man ever steps into the same river twice". It makes my thinking nimble: what a simple but incredibly effective way to represent time. Ambiguous, a snapshot, a reality of that exact time, never the same, and an infinite loop.

On the stone sides: "Per sempre". "Ti amo". Some messages are scratched into the stone; others calcified in permanent marker. Red. Black. Wear-resistant for a time – surely not forever. Ironic.

I saw these two rivers that are the same river in Marijke van Warmerdam's exhibition Then, now, and then at the Landhuis Oud Amelisweerd, where I went on the last Saturday it was open, in November 2022. Sure – I wanted to see this exhibition right away, but I didn't have time. And that was true, but only now as I write this do I understand its irony.

The work consists of two large screens side by side, free-standing displays installed in a room, on which two shots of the same river – but in different states – can be viewed. This makes you look more closely, searching for the constants where there is overlap and for what is different. Like the water's current, the films go on and on, in a loop. The water goes around, but not in the same artificial way as the hands of a clock.

For a moment I feel lighter. We can't experience the different currents at the same time, but we can imagine it, or fathom it, if we've seen it, like how this artwork makes me envision it, giving me a metaperspective that I cannot myself occupy, at least physically, but can adopt, spiritually.

Again I see a river. Again from a bridge. The same river, the same bridge. This time the water is rough. Foaming at the mouth. A fast current. The natural stone sides of the bridge display names, hearts, professions of love, promises.

I can take in these two rivers, that are and are not the same river, in a single view. I see this as a visual translation of Heraclitus' "no man ever steps into the same river twice". It makes my thinking nimble: what a simple but incredibly effective way to represent time. Ambiguous, a snapshot, a reality of that exact time, never the same, and an infinite loop.

On the stone sides: "Per sempre". "Ti amo". Some messages are scratched into the stone; others calcified in permanent marker. Red. Black. Wear-resistant for a time – surely not forever. Ironic.

I saw these two rivers that are the same river in Marijke van Warmerdam's exhibition Then, now, and then at the Landhuis Oud Amelisweerd, where I went on the last Saturday it was open, in November 2022. Sure – I wanted to see this exhibition right away, but I didn't have time. And that was true, but only now as I write this do I understand its irony.

The work consists of two large screens side by side, free-standing displays installed in a room, on which two shots of the same river – but in different states – can be viewed. This makes you look more closely, searching for the constants where there is overlap and for what is different. Like the water's current, the films go on and on, in a loop. The water goes around, but not in the same artificial way as the hands of a clock.

For a moment I feel lighter. We can't experience the different currents at the same time, but we can imagine it, or fathom it, if we've seen it, like how this artwork makes me envision it, giving me a metaperspective that I cannot myself occupy, at least physically, but can adopt, spiritually.

Before humans made clocks, there was already a clock, and still is. That of nature, the moon, the sun. Which influence the tides. The link between water and time, you see, is a primordial one. Unlike our clock time, which more than anything else is a mold into which we all try to squeeze ourselves, water has different states. It can transform. Water is not a single thing; it is briefly something and potentially everything. "Whenever I take a shower I always wonder when the water was a cloud," as artist David Horvitz's neon work aptly puts it.

Nature was our first clock. The rhythm of the sun and moon: for ages we needed no more than to know when the sun rose and when it set. Those were the productive hours, the hours when there was something to see, when work could be done. You more or less knew when it was time for the harvest, but you could not set a clock to it; nature does not allow itself to be forced into such a granular record of time. After all, it depends on so many variables: temperature, rainfall – to name a few.

Humans developed clocks based on nature's rhythms – day and night, the seasons. First by using a stick in the ground, whose shadow indicated time. This is how sundials developed; one of the first – as far as we know – comes from Egypt and dates back to 1500 BC. People also used water clocks: you could read how much time had passed based on how much water had run off, like how an hourglass works. Sensible, since a sundial is useless if there's no sun or on a cloudy day. But also impractical, because water can freeze – and so, therefore, can time.

With the advent of the industrial revolution, humans gradually managed to "conquer" time: time began to determine the day's rhythm in the workplace, how long workers' breaks were, how much they were paid (derived from how much time they had worked), and finally the amount of free time they got. In Tempo: Il sogno di uccidere Chronos ("Time: The Dream to Kill Chronos", not yet translated into English), Guido Tonelli writes, "Humans, dreaming of capturing Chronos [the name the Greeks used to personify linear, measurable time], are dismayed to discover that in reality they have only made themselves captives."

The cycle of water is a beautiful metaphor for what is missing from our current Western and predominantly capitalist understanding of time. It resonates with the cyclicality that lives in each of us: that you cannot dictate the state you're in at a given hour; that productivity, to the extent we are used to it, is more likely a state we force upon ourselves. That social engineering has limits.

Nature was our first clock. The rhythm of the sun and moon: for ages we needed no more than to know when the sun rose and when it set. Those were the productive hours, the hours when there was something to see, when work could be done. You more or less knew when it was time for the harvest, but you could not set a clock to it; nature does not allow itself to be forced into such a granular record of time. After all, it depends on so many variables: temperature, rainfall – to name a few.

Humans developed clocks based on nature's rhythms – day and night, the seasons. First by using a stick in the ground, whose shadow indicated time. This is how sundials developed; one of the first – as far as we know – comes from Egypt and dates back to 1500 BC. People also used water clocks: you could read how much time had passed based on how much water had run off, like how an hourglass works. Sensible, since a sundial is useless if there's no sun or on a cloudy day. But also impractical, because water can freeze – and so, therefore, can time.

With the advent of the industrial revolution, humans gradually managed to "conquer" time: time began to determine the day's rhythm in the workplace, how long workers' breaks were, how much they were paid (derived from how much time they had worked), and finally the amount of free time they got. In Tempo: Il sogno di uccidere Chronos ("Time: The Dream to Kill Chronos", not yet translated into English), Guido Tonelli writes, "Humans, dreaming of capturing Chronos [the name the Greeks used to personify linear, measurable time], are dismayed to discover that in reality they have only made themselves captives."

The cycle of water is a beautiful metaphor for what is missing from our current Western and predominantly capitalist understanding of time. It resonates with the cyclicality that lives in each of us: that you cannot dictate the state you're in at a given hour; that productivity, to the extent we are used to it, is more likely a state we force upon ourselves. That social engineering has limits.

I was in Berlin a few years back, and there were posters scattered throughout the city that read "Nobody owns the beach". I found these posters fascinating, in part because of what they said and the fact that they were purely typographical, but mostly because they were usually near posters trying to sell me something: a hair product, a new type of beer, a dating app.

My first thought with "Nobody owns the beach" was, of course nobody owns the beach, can you imagine? But when I started thinking about it, I couldn't actually say how much nature really belongs to "itself". Conceptualizing (cultivating) nature for capitalist gain is our status quo. What's more, or maybe even by extension, nature is there for our recreation (an interpretation of "free time", which that same capitalism spawned). Thus is nature conquered, it has utility, and we use it instead of listen to it – or its rhythms.

What I didn't know at the time, but do now, is that these posters were by David Horvitz, and that he designed a tote bag with the same text. The tote bag, the bohemian bag that became cool, making the work a somewhat ironic commentary on capitalism. On the tote bag's inner label is a quote from none other than Rachel Carson: "On all these shores there are echoes of past and future: of the flow of time, obliterating yet containing all that has gone before; of the sea's eternal rhythms – the tides, the beat of surf shaping, changing, dominating; of the stream of life, flowing as inexorably as any ocean current, from past to unknown future."

Time and transformation come up frequently in Horvitz's works. His Nautical Dusk (2013) consists of a bell and a sign which reads:

Notice

For the current exhibition (from [Date] until [Date]) the gallery's normal closing time of 6pm will change to the time of each day's nautical dusk.

Today's closing time will be at ..........

I try to imagine how I would react if I came across this work in a gallery. I often think, ok, if I get to the gallery at 3pm, and they close at 5pm, then I still have two hours to look at everything. If the space closes earlier because nautical twilight has arrived, I would suddenly have less time to look at everything. The work is, as it were, an intervention: it puts everything on edge, a good way to make tangible how much hold time has on us and what that comes at the expense of, what it costs.

My first thought with "Nobody owns the beach" was, of course nobody owns the beach, can you imagine? But when I started thinking about it, I couldn't actually say how much nature really belongs to "itself". Conceptualizing (cultivating) nature for capitalist gain is our status quo. What's more, or maybe even by extension, nature is there for our recreation (an interpretation of "free time", which that same capitalism spawned). Thus is nature conquered, it has utility, and we use it instead of listen to it – or its rhythms.

What I didn't know at the time, but do now, is that these posters were by David Horvitz, and that he designed a tote bag with the same text. The tote bag, the bohemian bag that became cool, making the work a somewhat ironic commentary on capitalism. On the tote bag's inner label is a quote from none other than Rachel Carson: "On all these shores there are echoes of past and future: of the flow of time, obliterating yet containing all that has gone before; of the sea's eternal rhythms – the tides, the beat of surf shaping, changing, dominating; of the stream of life, flowing as inexorably as any ocean current, from past to unknown future."

Time and transformation come up frequently in Horvitz's works. His Nautical Dusk (2013) consists of a bell and a sign which reads:

Notice

For the current exhibition (from [Date] until [Date]) the gallery's normal closing time of 6pm will change to the time of each day's nautical dusk.

Today's closing time will be at ..........

I try to imagine how I would react if I came across this work in a gallery. I often think, ok, if I get to the gallery at 3pm, and they close at 5pm, then I still have two hours to look at everything. If the space closes earlier because nautical twilight has arrived, I would suddenly have less time to look at everything. The work is, as it were, an intervention: it puts everything on edge, a good way to make tangible how much hold time has on us and what that comes at the expense of, what it costs.

Horvitz wants to link the place, the situation, to our prevailing idea of time and to something that is always there with a rhythm of its own – nature. To make tangible how art in a gallery is part of the capitalist system, and he does so using only a bell, words, and a forced change of the closing time.

But also, with the dispersal of the "Nobody owns the beach" posters, the location where they hung (a large city) is synonymous with a place that is far from the beach or nature, or removed from it entirely. And suddenly it becomes clear – I would almost write "tangible" – how the two differ in rhythm and pace. Unnatural versus natural. Horvitz himself says, "A lot of my work is about reminding yourself that you are somewhere unique – in a spatial sense and a temporal sense. Imagine what it was like before time zones, when places had their own times. What time is it? Where exactly are we right now?" And about the other rhythms that determine our existence:

"To me, it is more interesting when something happens that you don't expect. I really despise keeping a schedule because for me that ruins a day. You already define what you are doing at a certain time and place, and that day is no longer open for something unexpected to happen. A few years ago I did two connected shows at Jan Mot in Brussels and Dawid Radziszewski in Warsaw. The shows opened the day my friend Jenny gave birth to her daughter, so no one knew exactly when the opening would be. I wanted it to be unknown, to complicate the gallery's calendrical system with the biological (and lunar?) rhythms of my friend's body. I've always been amused when Brooklyn Botanical Gardens would have their Sakura festival and none of the cherry trees would be in bloom yet, or the peak blooms would be over. The gardens would have to schedule it a year in advance for various reasons, but a tree will bloom when it wants to bloom. In Japan, the moments the trees blossom is the moment you celebrate Sakura. You are on the tree's schedule – it doesn't follow your Google calendar."

That we have the audacity to project our inclination towards social engineering onto nature's rhythms is now more obvious than ever. Many of us perfectly ignore the signs we're getting that the planet is in trouble and that we're not doing enough to combat the climate crisis. The centrality we have given ourselves as humans is so pervasive that we actually think we can solve this problem without having to act on it now. The fact that our own lives depend on all life around us hardly seems to breach this veil.

This far-reaching capitalization of nature in relation to our agendas – both in the literal and figurative sense – is further magnified in artist Hito Steyerl's hallucinatory video work Liquidity Inc. Steyerl emphasizes the multiformity of water, the cycle, the different phases something goes through, the different versions something can be, the infinite combinations that can be made between ideas that initially seem unrelated. In the first minutes of Liquidity Inc., we hear a voiceover from the perspective of water. While "I am liquidity incorporated" is heard, words like "as rainbow", "torrent", "cloud", and later "leak", "flood", "wave", "tsunami", "tears", "sweat", "ice", "flow", "weather", "stream", "twister" appear on the screen. In these forms, we can easily imagine ourselves as water.

Then more puzzling concepts follow: "polygons", "numbers", "capital", "statistic distribution", "risk". But perhaps not so puzzling after all, since we have already noted that water and time are linked. And time is money. Liquidity Inc., like all of Steyerl's works, is bizarre, stylistically multifarious, over the top, elusive. It is a complex visual essay in which, as a viewer, you are tossed to and fro. Which side are you really on? And which one is the morally correct point of view?

But also, with the dispersal of the "Nobody owns the beach" posters, the location where they hung (a large city) is synonymous with a place that is far from the beach or nature, or removed from it entirely. And suddenly it becomes clear – I would almost write "tangible" – how the two differ in rhythm and pace. Unnatural versus natural. Horvitz himself says, "A lot of my work is about reminding yourself that you are somewhere unique – in a spatial sense and a temporal sense. Imagine what it was like before time zones, when places had their own times. What time is it? Where exactly are we right now?" And about the other rhythms that determine our existence: