Silvia Gardini

In this conversation Silvia speaks about ‘The European Whistleblower Directive,’ EU legislation which gives guidance and a structure for financial institutions to provide safe reportage systems. She argues that this legislation is already applicable to art schools, and both demands and provides guidance for providing safe and accountability structures.

Silvia Gardini

Silvia Gardini is a visual artist and lawyer who studied LL.M Civil law and an L.L.M Criminal and Criminal Procedural law at the University of Leiden. She is currently studying at the Akademie der Bildenden Künste in Munich, Germany and is part of Engagement Arts NL.

Sol Archer (SA): In 2022, reports of serious and long-term abuse within the production of the TV show The Voice of Holland became public. Following this, the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science realised that something needed to be done about abuse in the culture sector, so they created a special commission tasked with researching transgressive behaviour and social safety in the creative industries. From the research of this commission, the Raad voor Culture (RvC) published a report, called Over de Grens with recommendations, part of which were made in conjunction with Mores.online. What do you think of this report?

WEBSITE:

WEBSITE:

The report Over de Grens by Raad voor Culture (in Dutch)

Silvia Gardini (SG): I have been studying the report quite closely, looking at the proposed measures. Kunstenbond, Platform BK, Platform ACCT, and Engagement Arts NL wrote together as the work group ‘Sociale Veiligheid’ of the Creatieve Coalitie, in a public letter to the state secretary Culture and Media Gunay Uslu detailing the things that we consider to be missing from these measures, and what needs to be done both in the creative industry as a whole and in academies.

We are calling for, among other things, a formal whistleblowing system, on a sectoral and institutional level, and also for a top-down and a bottom-up review of the sector. Students and everyone else in the sector need to be involved in this review. It cannot just be something that is simply imposed from above.

I will explain the whistleblowing system, but first, let me talk about Mores.online. One measure that we consider also to be missing from their recommendations is mediation and support. This is complicated in the RvC recommendations because they appear to advise that Mores.online can do this. However, Mores.online is only an external advisor. They offer confidentiality advisors training. But as external confidentiality advisors, they do not participate in arbitration. They can only assist in trying to get another party at the table, but they cannot be present themselves because they do not want to be seen as a mediation bureau. We are arguing that this is not sufficient and that there needs to be an independent mediation and reporting body.

SA: In a conversation with someone from Mores.online, I found out that they don’t have the authority to take that role. They can’t do both confidentiality and arbitration.

SG: Which is right. People underestimate how much liability is involved with assault cases. If there's no supervision or proper whistleblowing system, then there is a high risk that bad things happen to people to the extent of criminal offences like sexual assault.

To expect a victim of assault to sit at a negotiation table with the accused perpetrator is an absolutely inappropriate measure. These situations are in a way civil liability cases because even in police cases where there is physical harm it takes an average of two years for anything to happen. Until police have decided to pursue a criminal investigation, an assault report can be considered mainly a civil liability case, for both the institution and the alleged offender. The educational institution is responsible for providing a safe learning environment. If somebody comes to them to report that something has happened, a criminal judgement could take years. Until that judgement is made, the institution is liable for a civil case on the basis of their failure to provide a safe environment.

So, in the meantime, as a semi-public, educational institution, you have an obligation to have systems in place to ensure the physical and psychological safety of the person reporting, and by proxy, everyone involved, and not to act out of fear of being sued or something like that. There is a risk in this situation, that the institutions just point to Mores.online and say, ‘Hey, just go to them,’ and thereby divert the responsibility of actually taking measures themselves.

It should be visible in institutions that there is a standard procedure every time that there's a report, so that it doesn't get personal each and every time an issue is reported. A concrete measure that institutions could take, for example, is to say that as soon as a complaint is started both alleged perpetrator and victim are not allowed on the premises for a standard fixed time, two weeks, or three months, or whatever.

Standardisation. It sounds boring, it looks boring, but it's absolutely fundamental for a system to work. Without standard procedures, everything risks appearing like an individual decision, which could be taken personally, and then the institution is going to be afraid that the alleged perpetrator is going to react by claiming damages for insinuating that they are criminal offenders.

SA: And a standardised system massively diminishes the emotional barrier for a whistle-blower to come forward.

SG: Yes, because then you know what you're getting yourself into. Otherwise, it really depends on the person, the personality and the character of the person filing the report.

If something did happen, the person who was hurt is not in a position to be the main actor on an investigation. The institution must lead the investigation with the approval of the person making the report. It may be, for example, that the reporter does not want a formal case to be brought, they just want to earmark someone in the records. It could be that they say, ‘I can handle it, I'm fine, but the situation should be reported,’ that wish must be respected.

But to come back to Mores.online. Even if they get a lot of support, they don't have the authority to fulfil the expectations that institutions seem to have of them. Namely, that they become a sort of mediator. So that is why Engagement Arts NL, along with other actors, is calling for an ombudsman to be set up. Just as there is one for child care, or the financial sector, there should be one for creative industries.

The Over de Grens report also talks about a Kennisbank, a knowledge bank. But it still needs to be defined what they aim to do with a knowledge bank. Is it just a documentation centre? We do need a monitor. We do need data, for sure. We need somebody who helps with legislation. But what is missing now in the first place is actual help for people making a report. In terms of physical care, psychological care, and legal assistance.

*

All views expressed by Silvia Gardini in this interview were done so in personal capacity. They are the interviewees own and do not reflect those of either Hogan Lovells International LLP or Engagement Arts NL.

We are calling for, among other things, a formal whistleblowing system, on a sectoral and institutional level, and also for a top-down and a bottom-up review of the sector. Students and everyone else in the sector need to be involved in this review. It cannot just be something that is simply imposed from above.

I will explain the whistleblowing system, but first, let me talk about Mores.online. One measure that we consider also to be missing from their recommendations is mediation and support. This is complicated in the RvC recommendations because they appear to advise that Mores.online can do this. However, Mores.online is only an external advisor. They offer confidentiality advisors training. But as external confidentiality advisors, they do not participate in arbitration. They can only assist in trying to get another party at the table, but they cannot be present themselves because they do not want to be seen as a mediation bureau. We are arguing that this is not sufficient and that there needs to be an independent mediation and reporting body.

SA: In a conversation with someone from Mores.online, I found out that they don’t have the authority to take that role. They can’t do both confidentiality and arbitration.

SG: Which is right. People underestimate how much liability is involved with assault cases. If there's no supervision or proper whistleblowing system, then there is a high risk that bad things happen to people to the extent of criminal offences like sexual assault.

To expect a victim of assault to sit at a negotiation table with the accused perpetrator is an absolutely inappropriate measure. These situations are in a way civil liability cases because even in police cases where there is physical harm it takes an average of two years for anything to happen. Until police have decided to pursue a criminal investigation, an assault report can be considered mainly a civil liability case, for both the institution and the alleged offender. The educational institution is responsible for providing a safe learning environment. If somebody comes to them to report that something has happened, a criminal judgement could take years. Until that judgement is made, the institution is liable for a civil case on the basis of their failure to provide a safe environment.

So, in the meantime, as a semi-public, educational institution, you have an obligation to have systems in place to ensure the physical and psychological safety of the person reporting, and by proxy, everyone involved, and not to act out of fear of being sued or something like that. There is a risk in this situation, that the institutions just point to Mores.online and say, ‘Hey, just go to them,’ and thereby divert the responsibility of actually taking measures themselves.

It should be visible in institutions that there is a standard procedure every time that there's a report, so that it doesn't get personal each and every time an issue is reported. A concrete measure that institutions could take, for example, is to say that as soon as a complaint is started both alleged perpetrator and victim are not allowed on the premises for a standard fixed time, two weeks, or three months, or whatever.

Standardisation. It sounds boring, it looks boring, but it's absolutely fundamental for a system to work. Without standard procedures, everything risks appearing like an individual decision, which could be taken personally, and then the institution is going to be afraid that the alleged perpetrator is going to react by claiming damages for insinuating that they are criminal offenders.

SA: And a standardised system massively diminishes the emotional barrier for a whistle-blower to come forward.

SG: Yes, because then you know what you're getting yourself into. Otherwise, it really depends on the person, the personality and the character of the person filing the report.

If something did happen, the person who was hurt is not in a position to be the main actor on an investigation. The institution must lead the investigation with the approval of the person making the report. It may be, for example, that the reporter does not want a formal case to be brought, they just want to earmark someone in the records. It could be that they say, ‘I can handle it, I'm fine, but the situation should be reported,’ that wish must be respected.

But to come back to Mores.online. Even if they get a lot of support, they don't have the authority to fulfil the expectations that institutions seem to have of them. Namely, that they become a sort of mediator. So that is why Engagement Arts NL, along with other actors, is calling for an ombudsman to be set up. Just as there is one for child care, or the financial sector, there should be one for creative industries.

The Over de Grens report also talks about a Kennisbank, a knowledge bank. But it still needs to be defined what they aim to do with a knowledge bank. Is it just a documentation centre? We do need a monitor. We do need data, for sure. We need somebody who helps with legislation. But what is missing now in the first place is actual help for people making a report. In terms of physical care, psychological care, and legal assistance.

“The more you go beyond society's everyday rules, into ‘free’ spaces where there are no rules, the more people fall back on regressive, conservative structures of authority.”

In Belgium, they had the Genderkamer to provide this. There was, for example, a large case between theatre artists and a theatre producer. A group of persons spoke up, initiated a court case, and were represented by one lawyer, and the Genderkamer financed the legal costs of their case. I also think we need financial support for the legal costs for the people who have had a bad experience.

There are European guidelines that cover that, such as the Istanbul Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence against Women and Domestic Violence. There are institutional obligations to act on this EU legislation, but they have not been implemented in the Netherlands. Other countries, such as Belgium and France, are very much ahead. In France, there's a government body that supports and documents cases and makes information public.

I think there should be a Central Reporting Authority in the Netherlands too, which maintains annual records and provides support for survivors. By maintaining records, I don’t mean publishing the names of accused people, just figures, such as the number of reports that are being made per institution per year, and the actions taken.

SA: In terms of this kind of public support structure, this propositional authority, is there something currently which fulfils some of these roles? Is there a public prosecutor for this kind of cases? Or a general public prosecutor for cases that cross over from civil to criminal jurisdiction within the general professional law framework of the Netherlands?

SG: There are specific teams within the police force that are being trained for this, but they are systematically understaffed, under trained, and overworked. So, for example, let's say that somebody comes with a report to the police. They have a duty to get back to them within a couple of months. And then they have to make a decision on whether to pursue the case or not. Sometimes this takes over two years. In 2021 there were about 850 cases which had been waiting for over half a year. In 2020, the police only met their internal half-year deadline in a meagre 52% of the cases.

In these cases, the risk of retraumatisation because of this waiting is very high. Throughout the time they are waiting for a judgement, the victims may have to have to maintain their presence in the place where an assault took place, at work or at university.

There's also an inherent evidence problem with this type of case because there are typically not many witnesses. Evidence very much depends on statements, but in heavy cases of trauma, when someone is in a very stressful situation, they tend to lose their sense of time. This means that they may lose memory of an hour of an incident, for example, but can remember one minute, from second to second in great detail. When people make a report, the modus operandi of the police is to ask for a minute by minute account of what happened. And if there are inconsistencies, that means that this is an unreliable statement.

Obviously that way of taking a report does not work for these types of trauma. With these high-pressure memories, it can also lead to re-traumatisation, as a result of experiencing disbelief from the victim’s social environment. This can alter the way people respond emotionally, and alter the way they remember. There are many aspects to it, so acting fast with this type of case is super important.

Criminal law is an ultimum remedium when society has not been able to deal with an issue. Only as a very last resort do you use the monopoly of violence of the police as agents of the state to punish somebody and make things right again. It is absolutely the last resort.

Consider it a spectrum. At one end is criminal law, and at the other there is the self-management of an interpersonal situation, like, for example, something happens at the art school between two students which they sort out by themselves. Somewhere in the middle is where the responsibility of the institution enters. In between the informal and the very strict, legal, formal points on the spectrum.

It's a cliché to say that the ideal solution is always somewhere in the middle, but it really is, and there’s a sweet spot involved before the situation becomes polarised. If something happens with a professor, for example, then the sweet spot is somewhere between the student expressing an objection to what is happening. For example, saying, ‘It is colonial when you say this’ (it doesn’t always have to do with sexual assault or something), and the professor saying, ‘you can't say anything anymore, leave my class, you're dismissed.’

This all happens under the roof of the institution, which holds responsibility over these situations. It has to make sure that the two parties don't sit in their opposite corners and refuse to budge. They can't choose one side: as an employer, they need to protect their employees; as a semi-governmental educational institution, they need to protect their students. So, they have to make sure to stay out of that polarised situation.

SA: Within art schools, mostly there seem to be a number of nested top-down processes where academic administration is trying to produce a document which is more or less punitive, dealing with reporting cases of abuse and assault, for example, and with post-offence or post-crisis management.

Some departments and work groups seem to be trying to create a code of some kind, which is guidance-oriented, about how to negotiate the terms for sharing a space in such a way that this conflictual crisis doesn't happen. If a civil or criminal infraction, such as assault does happen, then you can pass it up the chain to the administration reporting framework, which then engages more directly with the law.

Within the department, there are very few if any people who are qualified to mediate in a legal situation, so it's important for them to know that there's a clear procedural framework for reporting. So that the appeal to the authority is clearly laid out and its process is standardised.

In a sense, buddy culture in art schools—where informal relationships are a major part of why people have historically been hired—have made accountability very difficult to implement because people naturally want to protect themselves by not acknowledging the actions of their friends.

SG: Yes. It's mostly fear and partially ego that drives a resistance to this current trend, and institutions have a tendency to protect themselves from a report.

If somebody reports something that could be a criminal offence, there can be no question of issuing a Non-Disclosure Agreement (NDA) about it, you know, trying to silence it, because if the case goes to criminal court, that will be a civil agreement and so will not hold up in that court.

Good standard practice, though, is for all the reports to be confidential.

As soon as a potentially severe report is received:

I think there should be a Central Reporting Authority in the Netherlands too, which maintains annual records and provides support for survivors. By maintaining records, I don’t mean publishing the names of accused people, just figures, such as the number of reports that are being made per institution per year, and the actions taken.

SA: In terms of this kind of public support structure, this propositional authority, is there something currently which fulfils some of these roles? Is there a public prosecutor for this kind of cases? Or a general public prosecutor for cases that cross over from civil to criminal jurisdiction within the general professional law framework of the Netherlands?

SG: There are specific teams within the police force that are being trained for this, but they are systematically understaffed, under trained, and overworked. So, for example, let's say that somebody comes with a report to the police. They have a duty to get back to them within a couple of months. And then they have to make a decision on whether to pursue the case or not. Sometimes this takes over two years. In 2021 there were about 850 cases which had been waiting for over half a year. In 2020, the police only met their internal half-year deadline in a meagre 52% of the cases.

In these cases, the risk of retraumatisation because of this waiting is very high. Throughout the time they are waiting for a judgement, the victims may have to have to maintain their presence in the place where an assault took place, at work or at university.

There's also an inherent evidence problem with this type of case because there are typically not many witnesses. Evidence very much depends on statements, but in heavy cases of trauma, when someone is in a very stressful situation, they tend to lose their sense of time. This means that they may lose memory of an hour of an incident, for example, but can remember one minute, from second to second in great detail. When people make a report, the modus operandi of the police is to ask for a minute by minute account of what happened. And if there are inconsistencies, that means that this is an unreliable statement.

Obviously that way of taking a report does not work for these types of trauma. With these high-pressure memories, it can also lead to re-traumatisation, as a result of experiencing disbelief from the victim’s social environment. This can alter the way people respond emotionally, and alter the way they remember. There are many aspects to it, so acting fast with this type of case is super important.

Criminal law is an ultimum remedium when society has not been able to deal with an issue. Only as a very last resort do you use the monopoly of violence of the police as agents of the state to punish somebody and make things right again. It is absolutely the last resort.

Consider it a spectrum. At one end is criminal law, and at the other there is the self-management of an interpersonal situation, like, for example, something happens at the art school between two students which they sort out by themselves. Somewhere in the middle is where the responsibility of the institution enters. In between the informal and the very strict, legal, formal points on the spectrum.

It's a cliché to say that the ideal solution is always somewhere in the middle, but it really is, and there’s a sweet spot involved before the situation becomes polarised. If something happens with a professor, for example, then the sweet spot is somewhere between the student expressing an objection to what is happening. For example, saying, ‘It is colonial when you say this’ (it doesn’t always have to do with sexual assault or something), and the professor saying, ‘you can't say anything anymore, leave my class, you're dismissed.’

This all happens under the roof of the institution, which holds responsibility over these situations. It has to make sure that the two parties don't sit in their opposite corners and refuse to budge. They can't choose one side: as an employer, they need to protect their employees; as a semi-governmental educational institution, they need to protect their students. So, they have to make sure to stay out of that polarised situation.

SA: Within art schools, mostly there seem to be a number of nested top-down processes where academic administration is trying to produce a document which is more or less punitive, dealing with reporting cases of abuse and assault, for example, and with post-offence or post-crisis management.

Some departments and work groups seem to be trying to create a code of some kind, which is guidance-oriented, about how to negotiate the terms for sharing a space in such a way that this conflictual crisis doesn't happen. If a civil or criminal infraction, such as assault does happen, then you can pass it up the chain to the administration reporting framework, which then engages more directly with the law.

Within the department, there are very few if any people who are qualified to mediate in a legal situation, so it's important for them to know that there's a clear procedural framework for reporting. So that the appeal to the authority is clearly laid out and its process is standardised.

In a sense, buddy culture in art schools—where informal relationships are a major part of why people have historically been hired—have made accountability very difficult to implement because people naturally want to protect themselves by not acknowledging the actions of their friends.

SG: Yes. It's mostly fear and partially ego that drives a resistance to this current trend, and institutions have a tendency to protect themselves from a report.

If somebody reports something that could be a criminal offence, there can be no question of issuing a Non-Disclosure Agreement (NDA) about it, you know, trying to silence it, because if the case goes to criminal court, that will be a civil agreement and so will not hold up in that court.

Good standard practice, though, is for all the reports to be confidential.

As soon as a potentially severe report is received:

Guarantee confidentiality.

Do not set up a meeting where you put the persons involved unannounced in the same room. This still happens, unfortunately.

Make sure that everything, every email, every message, that you send about it is clearly labelled confidential.

Make sure that if somebody writes an email describing what happened, that it is not forwarded to the accused person, saying, ‘Hey, what do you think?’ And ‘what was your take on this situation?’

WEBSITE:

We're basically talking about compliance. My legal work at Hogan Lovells is to advise Index 500 companies on compliance. Allow me to give a bit of legal background to whistleblowing. This is based on European legislation called the European Whistleblower Directive (Directive (EU) 2019/1937 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 October 2019 on the protection of persons who report breaches of Union law (europa.eu), which some countries have implemented, and some have not, or they had their own versions. The implementation bill passed the Senate on January 24, 2023.

Initially, the directive was written to counter economic offences as money laundering, corruption and fraud so that people in companies can report suspicious activities. It is not made for the creative sector specifically, but applies to both the public and private sector and therefore affects all semi-public institutions. Most universities and art academies are, from a legal perspective, semi-public institutions, so are covered by this directive.

The European Union already broke their brains over what such a system should look like because it has to count for every organisation/entity in the EU. All organisations of 50 employees or more have to have a stringent internal procedure for reporting misconduct.

According to the Whistleblower Authority in the Netherlands (Huis voor Klokkenluiders), in its Annual Report of 2022, most of its reports are about social safety, such as sexual harassment and transgressive behaviour. The main focus of the directive might have been on financial misdeeds, but why would financial offences be more serious than social ones? I would argue that the whistleblowing directive should directly apply to the creative industry, and it already does for sure apply to public institutions, such as educational institutions.

SA: Can you say something about what that responsibility structure looks like in the directive?

SG: There has to be an internal reporting system. It is strongly encouraged that an external adviser and a confidential adviser are appointed. This also mentions psychological, personal, or medical assistance to the reporter.

Key to this system is the principle of non-retaliation. Nothing bad can happen to you if you report. This is something I often see as a barrier for reporting in the creative industry, where the socio-economic position of the reporters is very often much more precarious than that of the person they are reporting. This hierarchy in socio-economic status’ and its dependency fosters a high-risk environment for abuse. And so, you need something like this to really break that circle.

SA: In terms of misdeeds of an interpersonal, social nature, where, I imagine, usually the person reporting is the victim rather than an observer, compared to say a financial misdeed, where perhaps someone reports a discrepancy in accounting that they have observed, does this non-retaliation protection framework get launched immediately upon the report being filed? Is there a kind of a period of investigation, where they look into things before a misdeed report gets investigated, and someone gets put on leave or whatever?

In terms of non-retaliation, I can imagine that if you have a contract for a position as a tax lawyer in a large company or something, you have quite a clear set of rights that can be protected. Does the directive give guidance on how a person could be protected from retaliation in a situation more like the informality of the creative industry, or for a student who could be graded down by a perpetrator's colleagues in retaliation, in a way that is difficult to prove?

SG: I think my answer is clearest if I give a description of how this goes in practice. Often very large companies have a centralised reporting platform. It is possible that you can go to your supervisor and report things confidentially, and then they will tell the Ethics and Integrity team. There is generally a separate Ethics and Integrity team with specialised job titles, especially in multinationals.

All the reports reach this team, whether formally or informally filed, and a company will very often have a digital platform where it's possible for people to file a report anonymously. People are then reminded of the non-retaliation clause and they receive a notification of receipt of their report, followed by its status after a number of weeks of what is being done. They are also notified of the closure of the investigation. When we do an investigation, we get the report and send the message of receipt so that the reporter is always informed that the investigation is open.

Then there are two bases that you conduct that investigation on—on documentation and on interview. So, you do research and you ask about what happened with who, where. You do fact gathering. When you interview people, you tell them that they need to keep both the content of the interview, and also the fact that it is even happening strictly confidential.

Then you report on the investigation at the end. This report is not made public so colleagues of the accused should not know about it. Sometimes it’s a very intimate situation, so it should not be circulated among the others anyway. It must be clear before launching the report: who will see it at the end, and who it goes to, as few people as possible should be involved. The people who receive the report should always be the same fixed persons doing these investigations unless the report is about them.

SA: What kind of protections can be launched for someone if they're reporting a situation in which they're the victim and they need protection immediately? Does the directive allow or give a framework for that? Or is that the responsibility of the company or the ethics department to establish?

SG: Honestly, I don't know. But I think the most important thing is that investigation is done thoroughly. And objectively. A standard process and adequate persons are key.

You've also mentioned or hinted at informal consequences. Obviously, certain measures, like, if you have to let somebody go or put someone on leave, will be announced, but the grounds for that decision will not be circulated. Informal retaliation from other people demonstrates a lack of faith in the process. So, there should be no secondary punishment from other employees. And then if there is, that also would have to be addressed in itself.

SA: Which would fall back into the same process, ultimately?

SG: More or less, yes, which is ideal, I guess. And hopefully not too idealistic.

SA: It's very important to hear from you this perspective because a lot of the people working at an art school on a departmental level don't have your training, experience, or specific interest. I think a lot of us are looking more towards guidance documents rather than mechanisms for investigation or punitive measures, and don’t have an understanding of what existing structures should be in place to handle a report, once it goes above guidance level.

SG: But it's also not their job! I gave a talk about power structures at an art school, and on that day their new Code of Conduct was introduced. People were like, what does it mean? What do I need to do with this?

I realised that they are scared of a blame game, and as soon as there’s blame in the air, everybody blocks. This can be avoided by presenting these measures as an understanding that the teachers have a signalling function in the field. By which I mean that each report has a signalling function that something is not right in one environment. And that very likely means it is not right in other classrooms as well. So that is, I think, the best way to approach it for the people who are not trained for this but are in a position of authority. They have a signalling responsibility for the conditions of the learning environment, then they will be happy to take a concern higher up the chain of responsibility.

SA: I think a huge amount of work has needed to be done for a really long time about the transparency of the processes and structures that do already exist. It can already be difficult to understand who is in place and who has responsibility within a school, even for basic practical questions. For a new or a guest teacher, for example, often very little is clear. From basic things like the room a class was meant to take place in, who has the keys, all the way up to who is responsible for registering a report of inappropriate behaviour.

SG: You don't really have such strong workers’ rights in the sector. The creative industry is a very informal environment, where a lot is based on things we cannot measure. Authority is based not on how much money you make, your position, or how many people you have working for you. It's based on a range of subjective notions of fame and significance. Authority is largely based on reputation, and that is also the reason why someone could be selected for a professorship.

In Germany, to be a professor you don’t need to hold any form of educational training, which I thought was quite ridiculous, for an institution offering education. There are reasons that freedom at art schools is relatively high. It's considered to be a good in and of itself. I'm not saying that it should be more like a school, where teachers tell you exactly what to do. Absolutely not. But I am saying that something needs to change. Because people are getting hurt, they have nowhere to go, and there are multiple people responsible for stopping this, who are not taking action out of fear. That doesn't seem like a safe environment to me.

SA: Or a free one.

SG: Exactly. The ironic thing is that the more you go beyond society's everyday rules, into ‘free’ spaces where there are no rules, people fall back on really regressive, conservative structures of authority. The patriarchy is alive and kicking at art schools.

Initially, the directive was written to counter economic offences as money laundering, corruption and fraud so that people in companies can report suspicious activities. It is not made for the creative sector specifically, but applies to both the public and private sector and therefore affects all semi-public institutions. Most universities and art academies are, from a legal perspective, semi-public institutions, so are covered by this directive.

The European Union already broke their brains over what such a system should look like because it has to count for every organisation/entity in the EU. All organisations of 50 employees or more have to have a stringent internal procedure for reporting misconduct.

According to the Whistleblower Authority in the Netherlands (Huis voor Klokkenluiders), in its Annual Report of 2022, most of its reports are about social safety, such as sexual harassment and transgressive behaviour. The main focus of the directive might have been on financial misdeeds, but why would financial offences be more serious than social ones? I would argue that the whistleblowing directive should directly apply to the creative industry, and it already does for sure apply to public institutions, such as educational institutions.

SA: Can you say something about what that responsibility structure looks like in the directive?

SG: There has to be an internal reporting system. It is strongly encouraged that an external adviser and a confidential adviser are appointed. This also mentions psychological, personal, or medical assistance to the reporter.

Key to this system is the principle of non-retaliation. Nothing bad can happen to you if you report. This is something I often see as a barrier for reporting in the creative industry, where the socio-economic position of the reporters is very often much more precarious than that of the person they are reporting. This hierarchy in socio-economic status’ and its dependency fosters a high-risk environment for abuse. And so, you need something like this to really break that circle.

SA: In terms of misdeeds of an interpersonal, social nature, where, I imagine, usually the person reporting is the victim rather than an observer, compared to say a financial misdeed, where perhaps someone reports a discrepancy in accounting that they have observed, does this non-retaliation protection framework get launched immediately upon the report being filed? Is there a kind of a period of investigation, where they look into things before a misdeed report gets investigated, and someone gets put on leave or whatever?

In terms of non-retaliation, I can imagine that if you have a contract for a position as a tax lawyer in a large company or something, you have quite a clear set of rights that can be protected. Does the directive give guidance on how a person could be protected from retaliation in a situation more like the informality of the creative industry, or for a student who could be graded down by a perpetrator's colleagues in retaliation, in a way that is difficult to prove?

SG: I think my answer is clearest if I give a description of how this goes in practice. Often very large companies have a centralised reporting platform. It is possible that you can go to your supervisor and report things confidentially, and then they will tell the Ethics and Integrity team. There is generally a separate Ethics and Integrity team with specialised job titles, especially in multinationals.

All the reports reach this team, whether formally or informally filed, and a company will very often have a digital platform where it's possible for people to file a report anonymously. People are then reminded of the non-retaliation clause and they receive a notification of receipt of their report, followed by its status after a number of weeks of what is being done. They are also notified of the closure of the investigation. When we do an investigation, we get the report and send the message of receipt so that the reporter is always informed that the investigation is open.

Then there are two bases that you conduct that investigation on—on documentation and on interview. So, you do research and you ask about what happened with who, where. You do fact gathering. When you interview people, you tell them that they need to keep both the content of the interview, and also the fact that it is even happening strictly confidential.

Then you report on the investigation at the end. This report is not made public so colleagues of the accused should not know about it. Sometimes it’s a very intimate situation, so it should not be circulated among the others anyway. It must be clear before launching the report: who will see it at the end, and who it goes to, as few people as possible should be involved. The people who receive the report should always be the same fixed persons doing these investigations unless the report is about them.

SA: What kind of protections can be launched for someone if they're reporting a situation in which they're the victim and they need protection immediately? Does the directive allow or give a framework for that? Or is that the responsibility of the company or the ethics department to establish?

SG: Honestly, I don't know. But I think the most important thing is that investigation is done thoroughly. And objectively. A standard process and adequate persons are key.

You've also mentioned or hinted at informal consequences. Obviously, certain measures, like, if you have to let somebody go or put someone on leave, will be announced, but the grounds for that decision will not be circulated. Informal retaliation from other people demonstrates a lack of faith in the process. So, there should be no secondary punishment from other employees. And then if there is, that also would have to be addressed in itself.

SA: Which would fall back into the same process, ultimately?

SG: More or less, yes, which is ideal, I guess. And hopefully not too idealistic.

SA: It's very important to hear from you this perspective because a lot of the people working at an art school on a departmental level don't have your training, experience, or specific interest. I think a lot of us are looking more towards guidance documents rather than mechanisms for investigation or punitive measures, and don’t have an understanding of what existing structures should be in place to handle a report, once it goes above guidance level.

SG: But it's also not their job! I gave a talk about power structures at an art school, and on that day their new Code of Conduct was introduced. People were like, what does it mean? What do I need to do with this?

I realised that they are scared of a blame game, and as soon as there’s blame in the air, everybody blocks. This can be avoided by presenting these measures as an understanding that the teachers have a signalling function in the field. By which I mean that each report has a signalling function that something is not right in one environment. And that very likely means it is not right in other classrooms as well. So that is, I think, the best way to approach it for the people who are not trained for this but are in a position of authority. They have a signalling responsibility for the conditions of the learning environment, then they will be happy to take a concern higher up the chain of responsibility.

SA: I think a huge amount of work has needed to be done for a really long time about the transparency of the processes and structures that do already exist. It can already be difficult to understand who is in place and who has responsibility within a school, even for basic practical questions. For a new or a guest teacher, for example, often very little is clear. From basic things like the room a class was meant to take place in, who has the keys, all the way up to who is responsible for registering a report of inappropriate behaviour.

SG: You don't really have such strong workers’ rights in the sector. The creative industry is a very informal environment, where a lot is based on things we cannot measure. Authority is based not on how much money you make, your position, or how many people you have working for you. It's based on a range of subjective notions of fame and significance. Authority is largely based on reputation, and that is also the reason why someone could be selected for a professorship.

In Germany, to be a professor you don’t need to hold any form of educational training, which I thought was quite ridiculous, for an institution offering education. There are reasons that freedom at art schools is relatively high. It's considered to be a good in and of itself. I'm not saying that it should be more like a school, where teachers tell you exactly what to do. Absolutely not. But I am saying that something needs to change. Because people are getting hurt, they have nowhere to go, and there are multiple people responsible for stopping this, who are not taking action out of fear. That doesn't seem like a safe environment to me.

SA: Or a free one.

SG: Exactly. The ironic thing is that the more you go beyond society's everyday rules, into ‘free’ spaces where there are no rules, people fall back on really regressive, conservative structures of authority. The patriarchy is alive and kicking at art schools.

SA: It's ludicrous!

Has there been much work around codifying safety in the Kunstakademie in Munich that you've been involved in or that you've been observing?

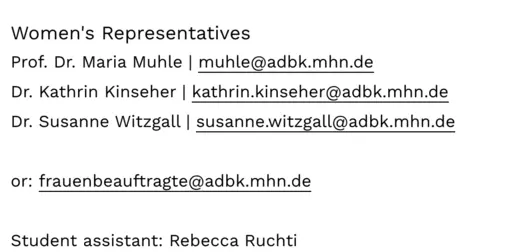

SG: Yeah, there has been a Frauenbeauftragte (Women’s Representatives) group who cover this work. It now consists of three people, and they are great. They are underfunded and overworked, but they are great people.

And there is a code of conduct. There was a code of conduct that was there from 2012, which was quite outdated in my opinion, and they reviewed and rewrote it this year. But apparently, they still have to call themselves Frauenbeauftragte (women representative) instead of something more gender neutral, but you know, they're working on it.

SA: How visible was the writing process to you as a student? And how important do you consider the visibility of that process to be?

SG: I think that's very important. In the end, it has to be student friendly. Right? It has to be accepted, accessible and understandable. For me, the best, the clearest, code of conduct is one with a decision tree that is practically a diagram. Absolutely not the type of thing that you have to pay lawyers to read through.

Has there been much work around codifying safety in the Kunstakademie in Munich that you've been involved in or that you've been observing?

SG: Yeah, there has been a Frauenbeauftragte (Women’s Representatives) group who cover this work. It now consists of three people, and they are great. They are underfunded and overworked, but they are great people.

And there is a code of conduct. There was a code of conduct that was there from 2012, which was quite outdated in my opinion, and they reviewed and rewrote it this year. But apparently, they still have to call themselves Frauenbeauftragte (women representative) instead of something more gender neutral, but you know, they're working on it.

SA: How visible was the writing process to you as a student? And how important do you consider the visibility of that process to be?

SG: I think that's very important. In the end, it has to be student friendly. Right? It has to be accepted, accessible and understandable. For me, the best, the clearest, code of conduct is one with a decision tree that is practically a diagram. Absolutely not the type of thing that you have to pay lawyers to read through.