Vulnerable Looking

Jules Sturm

Keywords:

visual thinking, vulnerability, disability aesthetics, art-making, embodied reflection, ableism, variation vs deviance, unlearning artistic and visual practices.

Tobin Siebers quoted in Mike Levin, ‘The Art of Disability: An Interview with Tobin Siebers,’ Disability Studies Quarterly, Vol. 30/2 (2010).

Tobin Siebers, ‘Disability Representation and the Political Dimension of Art,’ DESIGNABILITIES. Design Research Journal for Bodies, Things & Interaction (2014).

When critical disability theorist Tobin Siebers calls disability ‘the aesthetic object that makes modern art possible,’

Ibid..

The aim of this essay is to find partial and multiple answers to these questions: How do art, disability and vulnerability productively relate? How can ‘disability’ change not only the way we feel but also the way we look at others, ourselves, and the art we produce? And, finally, how can the concept of vulnerability—in addition to the individual experience and the universal human condition of vulnerability—become a tool for practising artists?

Introduction: On how the topic of “vulnerable looking” came Jules’ way.

Tobin Siebers develops the concept of disability aesthetics as a critique of aesthetic standards and tastes that exclude people with disabilities. Instead, he argues: ‘The idea of disability aesthetics affirms that disability operates both as a critical framework for questioning aesthetic presuppositions in the history of art and as a value in its own right important to future conceptions of what art is.’ (Siebers 2008) I use the notion of disability aesthetics here in an additional sense, by claiming that in aesthetic encounters we do not only involve our emotions and senses, but we also engage in specific bodily and cultural practices, such as seeing, reading, speaking, sculpting and writing. According to a disability approach to aesthetics, these should also be rethought and practised differently when looking at or when making art.

In an interview, Siebers explains: ‘[The] more artwork incorporates disability, the greater the chance […] to change the body politic.’

Siebers 2014.

My premise is that to participate in such an endeavour is never a simple question of an art work’s success or failure but includes a careful, slow, and sometimes frustrating engagement in the rethinking and unlearning of all the practices, material engagements, senses, and actors involved in the process of producing an art work. I hereby hope to contribute to expanding the tools for art-making and visual thinking towards a more inclusive and diverse aesthetics. I will use two of Marc Quinn’s sculptures of Alison Lapper, Alison Lapper Pregnant (image 1) and

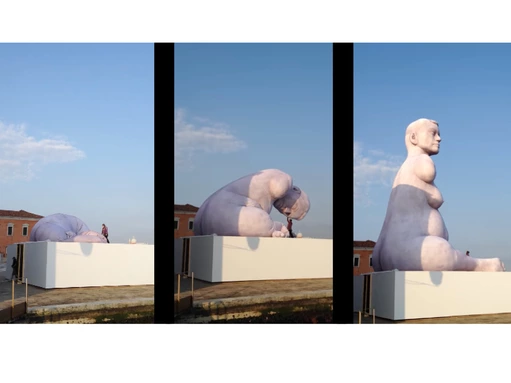

Let me now introduce the second of Quinn’s sculptures, called Breath (2012; see image 2), which offers us a timely insight into the vulnerability of our shared embodied dependencies on the availability of clean air and the functioning of our breathing organs.

The artwork’s title did not have the same brisance in 2012 as it currently has in the era of the Covid-19 pandemic. Writing this essay in early 2021 makes me more acutely aware of the necessity of a ‘critical aesthetic,’ an aesthetic which not only changes the representations of embodied human reality, but also of the way we perceive the world around us by way of bodily urgencies. For more reading on breath and vulnerability, refer to Magdalena Gorska’s ‘Breathing Matters’ (2016). Please also refer to Angelo Custódio’s valuable artistic work on breathing as embodied dialogue (2021). Custódio’s work is an important contribution to disability aesthetics in performative and sonic art in that ‘it explores the performative use of the voice to develop sonic encounters with the vulnerable’: foursistersproject.nl/en/calendar/breathing-sites-by-angelo-custodio-yara-said/.

Relational Vulnerability

Let me introduce the first sculpture: ‘[…] Alison Lapper Pregnant [is a] marble sculpture more than three meters tall, [portraying] the artist Alison Lapper, showing her nude and eight-months pregnant. It was on display in London for eighteen months (September 2005–April 2007) on Trafalgar Square’s fourth Plinth. Quinn’s sculpture, positioned in London’s crowded center alongside equestrian statues of such heroes of the British Empire as Lord Nelson, shows a self-confident, almost warrior-like woman, who suffers from phocomelia, a congenital condition that caused her to be born with shortened legs and without arms or hands. Cast as a statue in sleek white Italian marble, Lapper is depicted as a mother-to-be with a disabled body. The work caused some controversy: the statue was said to be powerful and inspiring as well as ugly and repellent. It elicits shamed yet fascinated reactions to the pregnant woman’s nakedness along with feelings of empowerment for people with disabilities. Alison Lapper’s own art aims to put disability, femininity, and motherhood on the map of public recognition. But does this representation of her as a disabled maternal subject manage to destabilize conventional aesthetic ideals and challenge ways of looking at disabled bodies in public?’Jules Sturm, Bodies We Fail. Productive Embodiments of Imperfection (Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag, 2014), pp. 77-79.

Listen to this fragment from an interview with Jules Sturm

In this fragment Sturm describes how she became interested in this scuplture, and how it was received by the public.

Judith Butler, Zeynep Gambetti, and Leticia Sabsay, eds. Vulnerability in Resistance (Duke University Press, 2016), p. 19.

In this sense, corporeality is ‘intercorporeality,’ which emphasises that ‘the experience of being embodied is never a private affair, but is always already mediated by our continual interactions with other human and nonhuman bodies.’

Gail Weiss, Body Images: Embodiment as Intercorporeality (New York: Routledge, 1999), p. 158

The sculpture unquestionably challenges conventional views of disabled bodies and motherhood and claims public recognition of so-called disruptive bodies. Yet, it does so without inviting its viewers to face their own cultural prejudices towards otherness or their internalised ableism.

‘Ableism is “a network of beliefs, processes and practices that produces a particular kind of self and body (the corporeal standard) that is projected as the perfect, species-typical and therefore essential and fully human. Disability then is cast as a diminished state of being human”. (Campbell 2001: 44) Ableism systematically interacts with other power structures that stigmatise to produce race, gender, sex, and disability. Ableism shapes our world and produces disability.’ Melinda C. Hall, ‘Critical Disability Theory,’ Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2019 edition), plato.stanford.edu/entries/disability-critical/.

These effects are potentially amplified here by its material attributes: ‘The stabilizing effect of the artwork’s surface quality enforces a seeming accuracy of vision, while vision itself, […] being under the constant threat of blindness, fails to see the complex (social and political) embodiment behind the clean façade.’

Sturm 2014, p. 80.

Sturm 2014, p. 81.

In this case, disability art, or disability aesthetics, offers the artist a resource to make a political statement. Yet, in contrast to the lived embodiment of the portrayed subject, Quinn’s marble sculpture fails to fully employ the aesthetic value of disability,

Siebers 2014.

Andries Hiskes, ‘The Affective Affordances of Disability,’ Digressions: Amsterdam Journal of Critical Theory, Cultural Analysis, and Creative Writing 3.2 (2019): pp. 5-17.

affordances as the way in which the form of the representation of disability may evoke affective responses such as fear, disgust, and admiration in viewers and readers.’ (Hiskes 2019, p. 5)

If we define disability as providing new resources for art makers, we must be careful—as with other experience- and identity-based qualities and reserves—not to: 1) instrumentalise disability for the sake of artistic (marketable) profit; 2) use the experience and appearance of people with disabilities as ‘inspiration’ to our art-making (Stella Young, inspiration porn); 3) employ disability as a metaphor for ‘otherness’ and ‘exoticism’ (Mitchell & Davis). Without wanting to presume Quinn’s own bearing on disability politics, his artworks suggest a certain inspirational stance towards disability.

‘Vulnerable,’ Merriam Webster, www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/vulnerability.

Listen to this fragment from an interview with Jules Sturm

This section of the essay talks about vision and visuality. In the added interview, you can hear Sturm talk about the way that surprisingly, it was literature that brought them to think about the visual. And how it was actually literature that started Jules’ interest in the visual.

‘Vulnerable,’ Merriam Webster, www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/vulnerability.

In addition to the more common definitions of vulnerability, American philosopher Judith Butler claims that vulnerability is relational: ‘[Vulnerability] is not a subjective disposition. Rather, it characterises a relation to a field of objects, forces, and passions that impinge on or affect us in some way. As a way of being related to what is not me and not fully masterable, vulnerability is a kind of relationship that belongs to that ambiguous region in which receptivity and responsiveness are not clearly separable from one another, and not distinguished as separate moments in a sequence; indeed, where receptivity and responsiveness become the basis for mobilizing vulnerability rather than engaging in its destructive denial.’

Butler in Butler, Gambetti, and Sabsay 2016, p. 25.

Listen to this fragment from an interview with Jules Sturm

American philosopher Judith Butler claims that vulnerability is relational.

Sturm 2014, p. 65.

How can vulnerability, then, help us to productively participate in disability aesthetics? The critical connection between vulnerability and disability art lies in the specificity of what happens in the process of viewing (or producing) the art object. In contrast to the visual relation with other art objects, the process here is experienced as potentially more vulnerable, or prone to wounding and uncertainty, and has an influence on our ways of looking and our forms of perception. If we consider art as a mode of perception, we can consider disability in art (or disability aesthetics) as introducing new modes of perception concerning human embodiment: more vulnerable modes of perception.

In contrast to, or in addition to, James Elkin’s revealing theory of how acts of seeing transform the seen object as well as the seeing subject (Elkins 1997), I here argue that acts of seeing disability in art transform our seeing.

Siebers in Levin 2010.

Listen to this fragment from an interview with Jules Sturm

On the promise of vulnerability strategically in art.

Breath

Let me now introduce the second of Quinn’s sculptures, calledLet me now introduce the second of Quinn’s sculptures, called Breath (2012; see image 2), which offers us a timely insight into the vulnerability of our shared embodied dependencies on the availability of clean air and the functioning of our breathing organs.

The artwork’s title did not have the same brisance in 2012 as it currently has in the era of the Covid-19 pandemic. Writing this essay in early 2021 makes me more acutely aware of the necessity of a ‘critical aesthetic,’ an aesthetic which not only changes the representations of embodied human reality, but also of the way we perceive the world around us by way of bodily urgencies. For more reading on breath and vulnerability, refer to Magdalena Gorska’s ‘Breathing Matters’ (2016). Please also refer to Angelo Custódio’s valuable artistic work on breathing as embodied dialogue (2021). Custódio’s work is an important contribution to disability aesthetics in performative and sonic art in that ‘it explores the performative use of the voice to develop sonic encounters with the vulnerable’: foursistersproject.nl/en/calendar/breathing-sites-by-angelo-custodio-yara-said/.

Let me now introduce the second of Quinn’s sculptures, called Breath (2012; see image 2), which offers us a timely insight into the vulnerability of our shared embodied dependencies on the availability of clean air and the functioning of our breathing organs.

The artwork’s title did not have the same brisance in 2012 as it currently has in the era of the Covid-19 pandemic. Writing this essay in early 2021 makes me more acutely aware of the necessity of a ‘critical aesthetic,’ an aesthetic which not only changes the representations of embodied human reality, but also of the way we perceive the world around us by way of bodily urgencies. For more reading on breath and vulnerability, refer to Magdalena Gorska’s ‘Breathing Matters’ (2016). Please also refer to Angelo Custódio’s valuable artistic work on breathing as embodied dialogue (2021). Custódio’s work is an important contribution to disability aesthetics in performative and sonic art in that ‘it explores the performative use of the voice to develop sonic encounters with the vulnerable’: foursistersproject.nl/en/calendar/breathing-sites-by-angelo-custodio-yara-said/.

The artwork’s title did not have the same brisance in 2012 as it currently has in the era of the Covid-19 pandemic. Writing this essay in early 2021 makes me more acutely aware of the necessity of a ‘critical aesthetic,’ an aesthetic which not only changes the representations of embodied human reality, but also of the way we perceive the world around us by way of bodily urgencies. For more reading on

Let me now introduce the second of Quinn’s sculptures, called Breath (2012; see image 2), which offers us a timely insight into the vulnerability of our shared embodied dependencies on the availability of clean air and the functioning of our breathing organs.

The artwork’s title did not have the same brisance in 2012 as it currently has in the era of the Covid-19 pandemic. Writing this essay in early 2021 makes me more acutely aware of the necessity of a ‘critical aesthetic,’ an aesthetic which not only changes the representations of embodied human reality, but also of the way we perceive the world around us by way of bodily urgencies. For more reading on breath and vulnerability, refer to Magdalena Gorska’s ‘Breathing Matters’ (2016). Please also refer to Angelo Custódio’s valuable artistic work on breathing as embodied dialogue (2021). Custódio’s work is an important contribution to disability aesthetics in performative and sonic art in that ‘it explores the performative use of the voice to develop sonic encounters with the vulnerable’: foursistersproject.nl/en/calendar/breathing-sites-by-angelo-custodio-yara-said/.

Let me now introduce the second of Quinn’s sculptures, called Breath (2012; see image 2), which offers us a timely insight into the vulnerability of our shared embodied dependencies on the availability of clean air and the functioning of our breathing organs.

The artwork’s title did not have the same brisance in 2012 as it currently has in the era of the Covid-19 pandemic. Writing this essay in early 2021 makes me more acutely aware of the necessity of a ‘critical aesthetic,’ an aesthetic which not only changes the representations of embodied human reality, but also of the way we perceive the world around us by way of bodily urgencies. For more reading on breath and vulnerability, refer to Magdalena Gorska’s ‘Breathing Matters’ (2016). Please also refer to Angelo Custódio’s valuable artistic work on breathing as embodied dialogue (2021). Custódio’s work is an important contribution to disability aesthetics in performative and sonic art in that ‘it explores the performative use of the voice to develop sonic encounters with the vulnerable’: foursistersproject.nl/en/calendar/breathing-sites-by-angelo-custodio-yara-said/.

Let me now introduce the second of Quinn’s sculptures, called Breath (2012; see image 2), which offers us a timely insight into the vulnerability of our shared embodied dependencies on the availability of clean air and the functioning of our breathing organs.

The artwork’s title did not have the same brisance in 2012 as it currently has in the era of the Covid-19 pandemic. Writing this essay in early 2021 makes me more acutely aware of the necessity of a ‘critical aesthetic,’ an aesthetic which not only changes the representations of embodied human reality, but also of the way we perceive the world around us by way of bodily urgencies. For more reading on breath and vulnerability, refer to Magdalena Gorska’s ‘Breathing Matters’ (2016). Please also refer to Angelo Custódio’s valuable artistic work on breathing as embodied dialogue (2021). Custódio’s work is an important contribution to disability aesthetics in performative and sonic art in that ‘it explores the performative use of the voice to develop sonic encounters with the vulnerable’: foursistersproject.nl/en/calendar/breathing-sites-by-angelo-custodio-yara-said/.

Let me now introduce the second of Quinn’s sculptures, called Breath (2012; see image 2), which offers us a timely insight into the vulnerability of our shared embodied dependencies on the availability of clean air and the functioning of our breathing organs.

The artwork’s title did not have the same brisance in 2012 as it currently has in the era of the Covid-19 pandemic. Writing this essay in early 2021 makes me more acutely aware of the necessity of a ‘critical aesthetic,’ an aesthetic which not only changes the representations of embodied human reality, but also of the way we perceive the world around us by way of bodily urgencies. For more reading on breath and vulnerability, refer to Magdalena Gorska’s ‘Breathing Matters’ (2016). Please also refer to Angelo Custódio’s valuable artistic work on breathing as embodied dialogue (2021). Custódio’s work is an important contribution to disability aesthetics in performative and sonic art in that ‘it explores the performative use of the voice to develop sonic encounters with the vulnerable’: foursistersproject.nl/en/calendar/breathing-sites-by-angelo-custodio-yara-said/.

Taken from Marc Quinn’s website.

What, then, does this artwork offer us in terms of artistic resources? It is not only the difference in material, presentation, technology, colour, or texture that makes a difference between the two sculptures discussed here. But it is also the artworks’ exposure to what Mieke Bal calls ‘embodied reflection’ that changes the way we look. Bal ascribes to artists the capacity to ‘mobilize art for an embodied reflection’.

Mieke Bal, ‘The Commitment to Look,’ Journal of Visual Culture 4/2 (2005): p. 153. Emphasis in original.

Sturm 2014, p. 81.

Listen to this fragment from an interview with Jules Sturm

Here Sturm explains the relation between the two sculptures in this audio fragment.

Let me now introduce the second of Quinn’s sculptures, called Breath (2012; see image 2), which offers us a timely insight into the vulnerability of our shared embodied dependencies on the availability of clean air and the functioning of our breathing organs.

The artwork’s title did not have the same brisance in 2012 as it currently has in the era of the Covid-19 pandemic. Writing this essay in early 2021 makes me more acutely aware of the necessity of a ‘critical aesthetic,’ an aesthetic which not only changes the representations of embodied human reality, but also of the way we perceive the world around us by way of bodily urgencies. For more reading on breath and vulnerability, refer to Magdalena Gorska’s ‘Breathing Matters’ (2016). Please also refer to Angelo Custódio’s valuable artistic work on breathing as embodied dialogue (2021). Custódio’s work is an important contribution to disability aesthetics in performative and sonic art in that ‘it explores the performative use of the voice to develop sonic encounters with the vulnerable’: foursistersproject.nl/en/calendar/breathing-sites-by-angelo-custodio-yara-said/.

This feeling is also motivated by the artwork’s skin-like texture, its growth from a heap of fabric through an embryonic posture to a sitting position, and by its continuous air intake, which appeal to basic bodily experiences we all share. How, then, does this impact on our practices of looking and on our participation in the production of alternative visions? Tobin Siebers is convinced that ‘the artwork makes us feel because of its unique physical properties, because of the way that it stands among us as a distinct physical manifestation. Art perception involves both perception of the artwork and self-perception.’

Siebers in Levin 2010.

Conclusion

In this essay, I made an attempt to consider more responsive and responsible forms of perception, which help to ‘reflect’ the world and ourselves through the shared experience of embodied vulnerability. To transform one’s own practice of looking, trained, for example, by engaging in disability art and vulnerability will be a potentially radical tool in one’s own art-making practices and in what such art-making can provoke. Technological changes in artistic tools, such as 3D graphics, photographic technologies and digital presentation formats, have reordered our relationship between visual perception and spatial and bodily experience. By introducing ‘tools’ such as vulnerability and disability aesthetics to our art making and visual practices, we will also more critically reorder artistic impact on the meaning making of ‘disability’ and other forms of culturally excluded forms of diverse and variant embodiment.In addition to exploring the ways in which certain art objects expose us to the vulnerability of ourselves and others, I hoped to have shown that such exposure can lead to embodied reflection, which in turn has the capacity to transform those (visual-cultural) practices we commonly use to produce and receive art. The goal must be to trouble our own looking, and thereby to produce forms of art that will eventually trouble visual culture for more diverse and just ways of looking at others.

Online Course

Want to delve further into the topic of this essay? Then take a look at the corresponding lesson that is part of anWant to delve further into the topic of this essay? Then take a look at the corresponding lesson that is part of an online course that consists of 10 lessons based on the 10 essays in this publication. These lessons focus on the central concepts that are treated in the essays and are followed by various questions, assignments and/or work formats.

The entire online course, including an extensive introduction, can be found via the button below. If you want to go directly to the assignments for this essay, click here.

The entire

Want to delve further into the topic of this essay? Then take a look at the corresponding lesson that is part of an online course that consists of 10 lessons based on the 10 essays in this publication. These lessons focus on the central concepts that are treated in the essays and are followed by various questions, assignments and/or work formats.

The entire online course, including an extensive introduction, can be found via the button below. If you want to go directly to the assignments for this essay, click here.

Reading List

Let me now introduce the second of Quinn’s sculptures, called Breath (2012; see image 2), which offers us a timely insight into the vulnerability of our shared embodied dependencies on the availability of clean air and the functioning of our breathing organs.

The artwork’s title did not have the same brisance in 2012 as it currently has in the era of the Covid-19 pandemic. Writing this essay in early 2021 makes me more acutely aware of the necessity of a ‘critical aesthetic,’ an aesthetic which not only changes the representations of embodied human reality, but also of the way we perceive the world around us by way of bodily urgencies. For more reading on breath and vulnerability, refer to Magdalena Gorska’s ‘Breathing Matters’ (2016). Please also refer to Angelo Custódio’s valuable artistic work on breathing as embodied dialogue (2021). Custódio’s work is an important contribution to disability aesthetics in performative and sonic art in that ‘it explores the performative use of the voice to develop sonic encounters with the vulnerable’: foursistersproject.nl/en/calendar/breathing-sites-by-angelo-custodio-yara-said/.

Let me now introduce the second of Quinn’s sculptures, called Breath (2012; see image 2), which offers us a timely insight into the vulnerability of our shared embodied dependencies on the availability of clean air and the functioning of our breathing organs.

The artwork’s title did not have the same brisance in 2012 as it currently has in the era of the Covid-19 pandemic. Writing this essay in early 2021 makes me more acutely aware of the necessity of a ‘critical aesthetic,’ an aesthetic which not only changes the representations of embodied human reality, but also of the way we perceive the world around us by way of bodily urgencies. For more reading on breath and vulnerability, refer to Magdalena Gorska’s ‘Breathing Matters’ (2016). Please also refer to Angelo Custódio’s valuable artistic work on breathing as embodied dialogue (2021). Custódio’s work is an important contribution to disability aesthetics in performative and sonic art in that ‘it explores the performative use of the voice to develop sonic encounters with the vulnerable’: foursistersproject.nl/en/calendar/breathing-sites-by-angelo-custodio-yara-said/.

Let me now introduce the second of Quinn’s sculptures, called Breath (2012; see image 2), which offers us a timely insight into the vulnerability of our shared embodied dependencies on the availability of clean air and the functioning of our breathing organs.

The artwork’s title did not have the same brisance in 2012 as it currently has in the era of the Covid-19 pandemic. Writing this essay in early 2021 makes me more acutely aware of the necessity of a ‘critical aesthetic,’ an aesthetic which not only changes the representations of embodied human reality, but also of the way we perceive the world around us by way of bodily urgencies. For more reading on breath and vulnerability, refer to Magdalena Gorska’s ‘Breathing Matters’ (2016). Please also refer to Angelo Custódio’s valuable artistic work on breathing as embodied dialogue (2021). Custódio’s work is an important contribution to disability aesthetics in performative and sonic art in that ‘it explores the performative use of the voice to develop sonic encounters with the vulnerable’: foursistersproject.nl/en/calendar/breathing-sites-by-angelo-custodio-yara-said/.

Let me now introduce the second of Quinn’s sculptures, called Breath (2012; see image 2), which offers us a timely insight into the vulnerability of our shared embodied dependencies on the availability of clean air and the functioning of our breathing organs.

The artwork’s title did not have the same brisance in 2012 as it currently has in the era of the Covid-19 pandemic. Writing this essay in early 2021 makes me more acutely aware of the necessity of a ‘critical aesthetic,’ an aesthetic which not only changes the representations of embodied human reality, but also of the way we perceive the world around us by way of bodily urgencies. For more reading on breath and vulnerability, refer to Magdalena Gorska’s ‘Breathing Matters’ (2016). Please also refer to Angelo Custódio’s valuable artistic work on breathing as embodied dialogue (2021). Custódio’s work is an important contribution to disability aesthetics in performative and sonic art in that ‘it explores the performative use of the voice to develop sonic encounters with the vulnerable’: foursistersproject.nl/en/calendar/breathing-sites-by-angelo-custodio-yara-said/.

Let me now introduce the second of Quinn’s sculptures, called Breath (2012; see image 2), which offers us a timely insight into the vulnerability of our shared embodied dependencies on the availability of clean air and the functioning of our breathing organs.

The artwork’s title did not have the same brisance in 2012 as it currently has in the era of the Covid-19 pandemic. Writing this essay in early 2021 makes me more acutely aware of the necessity of a ‘critical aesthetic,’ an aesthetic which not only changes the representations of embodied human reality, but also of the way we perceive the world around us by way of bodily urgencies. For more reading on breath and vulnerability, refer to Magdalena Gorska’s ‘Breathing Matters’ (2016). Please also refer to Angelo Custódio’s valuable artistic work on breathing as embodied dialogue (2021). Custódio’s work is an important contribution to disability aesthetics in performative and sonic art in that ‘it explores the performative use of the voice to develop sonic encounters with the vulnerable’: foursistersproject.nl/en/calendar/breathing-sites-by-angelo-custodio-yara-said/.

Let me now introduce the second of Quinn’s sculptures, called Breath (2012; see image 2), which offers us a timely insight into the vulnerability of our shared embodied dependencies on the availability of clean air and the functioning of our breathing organs.

The artwork’s title did not have the same brisance in 2012 as it currently has in the era of the Covid-19 pandemic. Writing this essay in early 2021 makes me more acutely aware of the necessity of a ‘critical aesthetic,’ an aesthetic which not only changes the representations of embodied human reality, but also of the way we perceive the world around us by way of bodily urgencies. For more reading on breath and vulnerability, refer to Magdalena Gorska’s ‘Breathing Matters’ (2016). Please also refer to Angelo Custódio’s valuable artistic work on breathing as embodied dialogue (2021). Custódio’s work is an important contribution to disability aesthetics in performative and sonic art in that ‘it explores the performative use of the voice to develop sonic encounters with the vulnerable’: foursistersproject.nl/en/calendar/breathing-sites-by-angelo-custodio-yara-said/.