How is Affect Related to the Social?

Eliza Steinbock

Keywords:

Affect; embodied experience; microphysics of power; theory-in-the-flesh; Zanele Muholi

Gilles Deleuze, Expressionism in Philosophy, trans. Martin Joughin (Princeton, M.A.: Zone Books, 1992).

John Dewey, Art as Experience (New York: Capricorn Books, 1934).

Susanne K. Langer, Feeling and Form: A Theory of Art (New York: Scribner, 1953).

Gilles Deleuze, Francis Bacon: The Logic of Sensation, trans. Daniel W. Smith (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1981).

Derek Matravers, Art and Emotion (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001).

Ernst van Alphen, ‘Affective Operations of Art and Literature,’ RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics 53/54 (Spring/Autumn 2008): pp. 21-30; see also Ernst van Alphen and Tomáš Jirsa (eds), How to Do Things with Affects: Affective Triggers in Aesthetic Forms and Cultural Practices (Leiden: Brill Rodopi, 2019).

Learning to Think Critically about Affect

There is no life without sensation. Affect studies provides a set of vocabulary that scholars, artists, and artistic researchers can employ to grope towards and grasp what is hard to pin down: sensation, feeling, a doing and undoing to the body, a happening that is underway.Gregory J. Seigworth and Melissa Gregg, ‘An Inventory of Shimmers,’ in: Gregory J. Seigworth and Melissa Gregg (eds), The Affect Theory Reader (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010), pp. 1-28.

Allow me to begin with a sketch of affect’s prehistory to better situate the demarcations of feminist theory. In Western Eurocentric philosophies, the Aristotelian split established in the fourth century B.C. between logos (appealing to reason), ethos (appealing to authority) and pathos (appealing to emotion) has defined the three main rhetorical tools that persuade ‘social actors,’ that is, any member of a society addressed in speech or discourse.

Aristotle, ‘Rhetoric by Aristotle,’ trans. W. Rhys Roberts, The Internet Classics Archive, classics.mit.edu/Aristotle/rhetoric.1.i.html.

René Descartes, A Discourse on Method: Meditations and Principles [1637], trans. John Veitch (London: Orion Publishing Group, 2004).

Frederic Schwartz, ‘“The Motions of the Countenance”: Rembrandt’s Early Portraits and the Tronie,’ RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics 17, no. 1 (1989): pp. 89-116.

Charles Darwin, The Expression of Emotion in Man and Animals (UK: John Murray, 1872).

In all cases of these prehistories, affect is tracked for its power: to persuade society, to disturb rational thought, to convey a type of selfhood. In the twentieth century, the major routes of studying how the feeling body knows and how to read the signs of affect consolidated into the theories of phenomenology and psychoanalysis (later psychology) respectively. Both of these branches have been inspirational for artists of all stripes but have also become reliable theoretical frameworks for the analysis of works of art.

Affect is a feminist problem in the sense that these prehistories champion a model of a sovereign, universal personhood that is, in fact, neither. The feminist insight is that this foregoing model relies on the split of mind from body, thought from emotion; further, the split aspects of personhood acquire an association with positive and negative values (mind and thought being more valued than body and emotion). These split aspects then become associated to larger, master narratives that hierarchise binaries of man (mind) / woman (body), white (thought) / black (emotion), human (cognition) / animal (intuition). The feminist author bell hooks famously called these interlocking systems of oppression the imperialist, white supremacist, capitalist, heteropatriarchy.

bell hooks, Feminist Theory: From Margin to Centre (Boston: South End Press, 1984).

Ann Cvetkovich, Depression: A Public Feeling (Durham: Duke University Press, 2012).

Cf. Franz Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks, new foreword by Kwame Anthony Appiah (New York: Grove Publishing, 2008); and Sara Ahmed, ‘Affective Economies,’ Social Text 22, no. 2 (2004): pp. 117-139; Ann Cvetkovich, An Archive of Feelings (Durham: Duke University Press, 2003); Eliza Steinbock, ‘Framing Stigma in Trans* Mediascapes: How Does it Feel to Be a Problem?’ Spectator 37, no. 2 (2017): pp. 48-57.

Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison [1975], trans. Alan Sheridan (New York: Vintage, 2012).

Seigworth and Gregg 2010, p. 1.

The affective turn is dated to the increase since the mid-1990s in humanities and social scientist scholarship engaging with the notion that what is felt ‘is neither internally produced nor simply imposed on us from external ideological structures.’

Jenny Rice, ‘The New “New”: Making a Case for Critical Affect Studies,’ Quarterly Journal of Speech, 94, no. 2 (2008): pp. 200–212; p. 205.

A key source is This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color, first published in 1981, edited by Cherríe Moraga and Gloria Anzaldúa, that propelled the idea of Third World Feminism.

Cherríe Moraga and Gloria Anzaldúa (eds), This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color (New York: Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press, 1981).

Cherríe Moraga, ‘Preface,’ in: Cherríe Moraga and Gloria Anzaldúa (eds), This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color (New York: Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press, 1981), pp. xiii-xix; p. xviii.

Moraga, ‘Preface,’ 1981, p. xviii.

Cherríe Moraga, ‘Entering the Lives of Others: Theory in the Flesh,’ in: Cherríe Moraga and Gloria Anzaldúa (eds), This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color (New York: Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press, 1981), p. 23.

Juana María Rodríguez, Sexual Futures: Queer Gestures and Other Latina Longings (New York: New York University Press, 2014), p. 17.

Learning to Work Differently with Affect

Critical affect studies are thus infused with critiques coming out of postcolonial, queer, ethnicity and race, disability, intersex and trans theories that challenge the notion of a universal or baseline way of feeling, instead showing how affect can become weaponised or made into a technology of oppression, and likewise be a powerful source of knowledge and activist fuel. As the quote from Moraga above indicates, too often feeling bad or excessive is what it means to feel brown, black, yellow and red.See José Esteban Muñoz, The Sense of Brown, edited with an introduction by Joshua Chambers-Letson and Tavia Nyong’o (Durham: Duke University Press, 2020). Sianne Ngai, Ugly Feelings (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007).

Audre Lorde, ‘The Uses of Anger: Women Responding to Racism,’ Keynote presentation at the National Women’s Studies Association Conference, Storrs, Connecticut, June 1981, in: Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches [1984] (Freedom, CA: The Crossing Press, 1997), p. 124-133; p. 124, 127, 130.

Lorde, ‘The Uses of Anger’, p. 127.

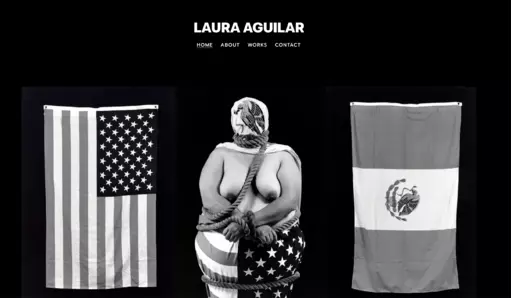

WEBSITE:

WEBSITE:

WEBSITE:

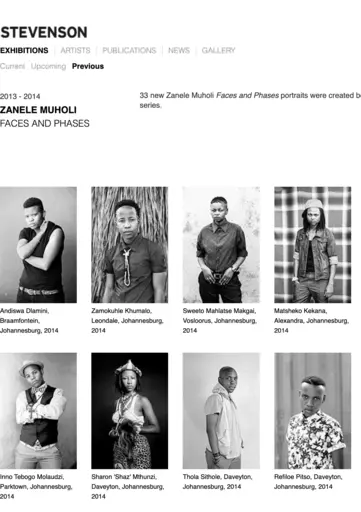

Exhibition view Zanele Muholi at Stedelijk Museum à Amsterdam, Series Faces and Phases, 2006-2017.

Foto Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam / Gert Jan van Rooij. With permission signed by STEVENSON on behalf of Zanele Muholi.

Zanele Muholi, Faces and Phases (2006-2014), NY: The Walter Collection, 2014 and Göttingen, Germany: Steidl, 2014.

Muholi, Faces and Phases, p. 6.

The visual project enabled documentation, which at the same time was the creation of an archive where there was none. Additionally, anger at the dominant representation of the Black women as suffering guides Muholi’s aesthetic choices such as the tone and framing of the portraits, as well as their installation in a tightly arranged grid. These choices aim to reconfigure the predominant context of power relations hold together by ‘sticky’ affects like happiness and suffering, which feminist writer Sara Ahmed has described as when affects are ‘what sticks, or what sustains or preserves the connection between ideas, values, and objects.’

Sara Ahmed, ‘Happy Objects,’ in: Gregory J. Seigworth and Melissa Gregg (eds), The Affect Theory Reader (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010), p. 29-51; p. 29.

Deborah Willis with Zanele Muholi, ‘Zanele Muholi’s Faces and Phases,’ Aperature April 21, 2015, aperture.org/editorial/magazine-zanele-muholis-faces-phases/.

Muholi has described the political tone of the artistic portraits as ‘Not for show. Not for play.’ To only be art and aestheticised risks the portrayed being objectified, or the act of portraiture reduced to empty fun. Where these earlier images show acts of mourning and suffering women, a common trope in photo journalism and human rights documentation, Muholi’s portraits of composed, self-contained subjects exude a quiet power.

Marta Zarzycka, Gendered Tropes in War Photography: Mothers, Mourners, Soldiers (New York: Routledge, 2016).

Gabeba Baderoon, ‘Composing Selves: Zanele Muholi’s Faces and Phases as an Archive of Collective Being,’ in: Zanele Muholi, Faces and Phases (2006-2014), NY: The Walter Collection, 2014 and Göttingen, Germany: Steidl, 2014, pp. 327- 338.

Looking through the artist’s monograph Faces and Phases, the portraits are interspersed with writings from the sitters. This format allows for the reader to potentially generate intimacy with each person, to think about their lives beyond and in the frame; to contemplate the idiosyncratic clothing choices and posture, the expression of defiance, an unguarded pose, a knowingness creeping into lips that almost start to smile. However, in the installations of Faces and Phases, which I have experienced in Amsterdam twice, Berlin, Brooklyn, and Johannesburg, the group staging of the images makes a forceful impact, overwhelming in their larger than life prints and the affixture of numerous eyes directed at the viewer.

Joseph Underwood, ‘Zanele Muholi: Faces and Phases 3 Years, 3 Continents, 3 Venues,’ Another Africa, October 2, 2015, www.anotherafrica.net/art-culture/zanele-muholi-faces-and-phases-3-years-3-continents-3-venues.

I witnessed such a lively event complete with the happy shrieks of greetings, dancing, group photos and selfie taking, a wall to add one’s own quote, a generous free sit-down meal, and the option to return for walk-throughs by the participants. The effect of the event of displaying the portraits as a whole was joyous and celebratory of a people, not only of a person. As a white non-South African, a double-outsider, I sensed the ripples of disrupted white affect that typically permeates such elite spaces as art galleries, in which whiteness is, according to performance studies scholar José E. Muñoz a ‘cultural logic that prescribes and regulates national feelings and comportment.’

José Esteban Muñoz, ‘Feeling Brown, Feeling Down: Latina Affect, the Performativity of Race, and theDepressive Position,’ Signs 31 no. 3 (2006): pp. 675-688; p. 680.

Wendy V. Muñiz, ‘Public Thinker: Frances Negrón-Muntaner on Puerto Rico, Art, and Decolonial Joy,’ Public Books, December 12, 2019, www.publicbooks.org/public-thinker-frances-negron-muntaner-on-puerto-rico-art-and-decolonial-joy/.

In closing, affect as a tool could be seen as a spotlight, as in Lorde’s terms, a socially embedded feeling that works like a precision tool to define and direct the work of dismantling systemic oppressions. You might ask yourself how affect carries with it a social judgement or evaluation. What is the ‘bad feeling’ and who is asked to carry it, or hold discomfort? How does affect form a relation between people-objects-technologies-social worlds? What kind of intensification occurs through a particular art work? In your body in relation to it? How would you describe that ‘something’ that seems to saturate the environment? The goal of using affect as a tool, I will offer, is to pay attention to how affect is being directed and configured within a social relation, and as an artist to practise in a critical and aware manner how affect is generated in the relations and in the bodies of those engaging with your art.

Online Course

Want to delve further into the topic of this essay? Then take a look at the corresponding lesson that is part of anWant to delve further into the topic of this essay? Then take a look at the corresponding lesson that is part of an online course that consists of 10 lessons based on the 10 essays in this publication. These lessons focus on the central concepts that are treated in the essays and are followed by various questions, assignments and/or work formats.

The entire online course, including an extensive introduction, can be found via the button below. If you want to go directly to the assignments for this essay, click here.

The entire

Want to delve further into the topic of this essay? Then take a look at the corresponding lesson that is part of an online course that consists of 10 lessons based on the 10 essays in this publication. These lessons focus on the central concepts that are treated in the essays and are followed by various questions, assignments and/or work formats.

The entire online course, including an extensive introduction, can be found via the button below. If you want to go directly to the assignments for this essay, click here.