Critical Tactics in Participatory Art

Fabiola Camuti

Keywords:

Participatory Art, Critical Tactics, Artist Educator, Prison Theatre, Accessibility, Agency, Articulation

Participatory Art: A Perspective from a Case Study

Until not too long ago, the correlation between art and its societal application was understood mostly, if not solely, through the frame of art therapy. Art therapies are largely used by taking into account concepts of care and cure and are practised by trained arts therapists and regulated by professional bodies. However, other spheres of the artistic practices have started to receive increasing attention and artistic communities have begun to become actively involved in them. These practices have been named and labelled differently—sometimes according to the country in which these have been carried out, other times following the specificity of the artistic means put to use. Examples include socially engaged art, community-based art, or, in the specific case of theatre and performance, applied theatre and performance or social theatre.Participatory arts activities are typically facilitated directly by artists and then the active participation of everyone involved in the process. They refer to those practices wherein the people constitute the central artistic medium and material.

Claire Bishop, Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship (London and New York: Verso, 2012), p. 2.

Nicolas Bourriaud, Relational Aesthetics (Dijon: Presses du Réel, 2002). ‘Relational aesthetics’ is a term coined by art critic, historian and curator Nicolas Bourriaud, originally for the exhibition ‘Traffic,’ held at the CAPC Museum of Contemporary Art of Bordeaux in 1996. Bourriaud, who is inseparable from the concept, further expanded on the term in his 1998 book, Relational Aesthetics, defining the movement as: ‘A set of artistic practices which take as their theoretical and practical point of departure the whole of human relations and their social context, rather than an independent and private space’ (p. 113). Bourriaud cites the examples of art by Gillian Wearing, Philippe Parreno, Douglas Gordon and Liam Gillick as artists who work to this agenda.

Participatory art projects exist at the threshold of art and civic institutions and are unique in this sense because of their firm commitment to societal challenges and the aim of real transformation.

Sruti Bala, The Gesture of Participatory Art (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2018).

See Bishop, Artificial Hells.

See Bishop, Artificial Hells. Since the 1990s, the UK has positioned itself as a leading country in the field with a number of dedicated B.A. and M.A. courses and programmes on participatory art, as well as an ever-increasing number of projects and publications in the field. See the list of recommended literature for some examples.

Scroll down for the video about ‘the Acting Project: theatre and refugee integration in Greece’.

See Nicola Shaughnessy, ‘Acting in a World of Difference: Drama, Autism and Gender,’ Biblioteca Teatrale, no. 133 (2020): pp. 41-62; Anna Harpin, Madness, Art, and Society: Beyond Illness (Abingdon: Routlegde, 2018); Wenche Torrissen, Theo Stickley, ‘Participatory Theatre and Mental Health Recovery: A Narrative Inquiry’ in Perspectives in Public Health, vol. 138, issue 1 (2018): pp. 47-54.

I was part of a multidisciplinary research project that included participatory arts to look at the impact of theatre in improving the quality of life of incarcerated people. Between 2013 and 2016, the departments of Art History and Performing Art, where I was working, and Physiology and Pharmacology of Sapienza University of Rome started collaborating to investigate the potentially positive role of theatre. This work was carried out firstly inside prison and secondly with formerly incarcerated people on probation and/or in a post-release situation. The starting point of our research was considering the theatrical work as an ‘enriched environment’ for people in reclusion or in post-reclusion phase who found themselves in an impoverished situation as a result.

Enriched environment, or environmental enrichment, is a neurophysiological concept that refers to those processes of social, mental and physical stimulation that positively affect brain plasticity and functions.

Henriette van Praag, et al., ‘Neural Consequences of Environmental Enrichment,’ Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 1(3) (2000): pp. 191-198.

Alessandro Sale (ed.), Environmental Experience and Plasticity of the Developing Brain (Hoboken: Wiley Blackwell, 2016).

For a full account of the project, the experiment’s protocol, and related autoethnographical methodologies, see Ciancarelli, R., F. Camuti and A. Roma (eds.) Teatro come ambiente arricchito/Theatre as Enriched Environment, special issue of Biblioteca Teatrale, 111-112 (2014) (2016).

Even in the second phase of the project, when we focussed on the work carried out outside the prison with a group of formerly incarcerated people, the experience of the project forced us to reconsider our position as artists and makers and to sometimes even push the limits of what we thought were our initial goals and intentions.

The projects I was involved in lasted three years (2013-2016). My role in these projects was that of facilitator and researcher. I also worked closely with the director and the participants in the dramaturgical construction of the pieces. The theatre company inside the prison had already been active for more than ten years and produced more than twenty theatre performances in three different prison departments, with more than 100 participants, which had been shown in the space of the prison itself and outside in dedicated festivals. Some of the actors, who belonged to the theatre group working inside the Roman prison of Rebibbia and were part of the original project, have continued to work with the director Valentina Esposito when put on probation or post-release situation since 2014. This was unprecedented in Italy. It then resulted in the first theatre workshop conducted with formerly incarcerated people, who, in this specific case, have asked themselves (talking about agency and giving a different meaning to life experiences and life itself) to continue ‘doing theatre.’ The group is now a stable movie/theatre company (Fort Apache Cinema Teatro) consisting of twenty actors who are former inmates and other professional actors. They have produced three theatre performances, one movie, a number of workshops in schools and marginalised communities. The inmates work actively as actors/workshop facilitators. In addition, some of them have become professional actors outside the company, taking part in renowned movie and TV series productions (see www.fortapachecinemateatro.com/).

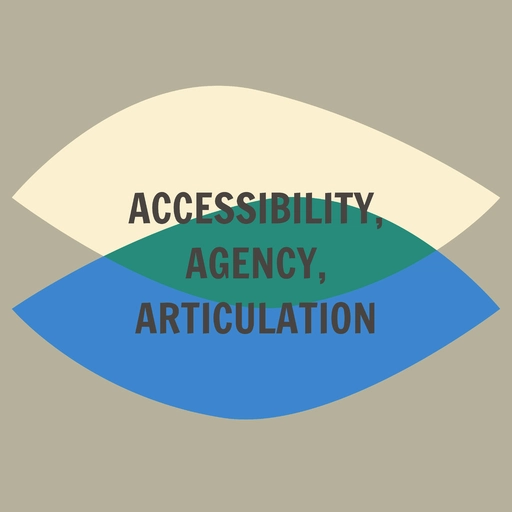

The Three A’s:

Articulation: process of co-creation vs representation.

Agency: capacity of individuals to have the power and resources to fulfill their potential.

Accessibility: the quality of a project to be open to everyone.

The Three A’s: How to Make Situated Participatory Art

In his The Practice of Everyday Life (published in 1984 in English), historian Michel de Certeau makes a clear distinction between two concepts that in a way regulate our everyday society: strategies and tactics. In very simple words, we can say that ‘strategies’ fall under the domain of what is ‘proper,’ institutional, or done by the rules. A strategy is a power relationship between institutions, which produce rules, and the individual, who is considered a customer to be managed. Some examples would be governmental rules that we abide by, or ‘proper’ behaviours we are all accustomed to in order to live in society.On the other hand, tactics insinuate into less normative spaces. They tend to cover those gaps left by societal rules. They are not ascribable to the role of the proper and are, by all means, disruptive and calculated actions, a struggle for life.

Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life (Berkley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, 1984), pp. 34-37.

What happens if, parallel to the institutional work we all often have to carry out to ensure the survival of the projects we care about, we forget about words such as impact, benefit, performance evaluation, etc.? Looking at the work through the lens of the perspective of critical tactics can free us from the need to be institutional and grant us access to a more creative way of approaching participatory intervention.

In what follows, I have provided a list of some of the critical tactics I have discovered during my work as artist educator and researcher in the field of prison theatre. I do so by grounding them in theoretical concepts from Donna Haraway’s philosophy.

Accessibility: The Foundation of Participatory Art

The first critical tactic I would like to address is, in my experience, valid for both participatory art and also any form of educational activity generally. I am referring to the concept of accessibility. We have to take into account the question of who has access to specific projects, who is allowed to take part in the activities, and, last but not least, how can we make it accessible to them in terms of, for example, time, location, and language.I would also like to consider the role of accessibility in questioning our roles as artist educators. How do we make ourselves accessible? Which kinds of knowledge do we want to offer, and from which perspective? And how do we use the knowledge we have in our practice? Participatory practices are situated in their own nature.

In her well-known ‘Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective’ (1988), feminist scholar Donna Haraway reflects on the blind hierarchical way of positioning sciences and different knowledges due to the patriarchal hegemony that rules academia and, I would add, very often artist practices.

In this instance, then, accessibility refers to the possibility of being open to the encounter, to the mandatory task of always taking the other’s perspective into account—not as a kind gesture but precisely because it is the complexity of perspectives that will complete the work. Situating the practice in an accessible space—not only physical and not just human but rather plural—is the first tool to consider if we want to establish a bridge between different experiences and opening up the possibility of creating new forms of kinship. Kinship, or ‘making kin,’ as Donna Haraway would probably say, refers to the ability to make yourself accessible to all kinds of possible interactions. That means with humans, of course, but not solely. Nature, natural elements, the space you are in, even stories—everything consists of something you can incorporate in your new relationship diagram.

On Donna Haraway and the concept of ‘making kin,’ I suggest watching the documentary Donna Haraway: Story Telling for Earthly Survivors by Fabrizio Terranova (2016).

Creating a kinship in a world that tends to isolate us, in a world that strives for individualism, can be the key to creating new, accessible communities. It entails a responsibility towards the newly found kin. So, for example, when working together with a group of people you seem to have nothing in common with, like the participants of the prison theatre project, you look for connections. And once you have found them, you cherish and safeguard them. In our case, the connection came through personal stories. We all shared difficult stories that were part of our lives, which made us all accessible to one another. This created a connection that we nurtured. Those same stories were often combined with the dramaturgy of the performance with the aim of opening up another accessible route to the public who would eventually hear them. Kinship is a way of creating an infinite network of connection while acknowledging the mutualism that exists between you and the other and the need for respect that this entails.

Agency: The Participants’ Ownership of the Process

Another point to take into account involves the participants’ agency. This is true for every step of the work—from the project’s genesis to its implementation, final presentation and evaluation. Referring again to Haraway, our work could include a firmer and more persistent contribution from the feminist perspective by introducing the concept of feminist objectivity‘Feminist objectivity’ or feminist epistemology tackles the idea of objectivism in science. It identifies how dominant conceptions and practices of knowledge attribution, acquisition, and justification disadvantage women and other subordinated groups, and strives to reform them to serve the interests of these groups.

Donna Haraway, ‘Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective,’ Feminist Studies vol. 14, no. 3 (1988): p. 581.

Haraway 1988, p. 583.

Haraway 1988, p. 590.

Stripping the subject of their own agency, their ownership, creates a lacuna of experiences that will never be filled by only presenting our account of the story; it can even put the completion of the work itself at risk. In working with formerly incarcerated people, we, the research and artistic team, made the mistake of not involving the participants in some important decision-making steps—for example, discussions around the methods of evaluation. The project, which was conducted together with a group of neurophysiologists, in fact required the collection of quantitative data to measure the beneficial impact of the theatrical work on the participants’ quality of life by means of psychometrics tools of evaluation and electroencephalography exams.

When confronted with the evaluation strategy, the participants categorically refused to continue. They felt betrayed precisely because we had stepped back into a strict division of roles, i.e. ‘we’ the researchers vs. ‘them’ the subjects. We learned from our mistakes. Looking only for empirical data to be collected has proven to be an unfulfilled goal, if not an obstacle, to the project’s success. The intense and fragile relationships built in participatory art projects are most likely to suffer if they prioritise numbers over the need of human connection (something that art can provide).

In our case, the combination of an autoethnographic approach—combining observation and narrative methodologies—has proven to be not only successful but also empowering because it stems from a participatory need. Everyone involved is taken into account in their own individualities and in their own biographies and experiences.

Autoethnography is a research method that uses the researcher's personal experience as data to describe, analyse, and understand cultural experience. It is a form of self-narrative that places the self within a social context. See Heewon Chang, Autoethnography as Method (New York: Routledge, 2016).

Articulation: Overcoming the Trap of Representation

Lastly in this list that became essential for me throughout the years is the concept of articulation. The risk for the artist educator, researcher, or maker is to fall into the trap of representation, becoming the spokesperson for a community they do not belong to. This kind of action will reproduce a patriarchal and colonial act in which the participants, who gave life to the project in the first place, are disempowered and put back into a minority position from which it is hard then to escape. This runs the risk of acting like a ‘white saviour’ who has done a good deed and is ready to move on to their next cause. A counter-proposal is that of delving into a politics of articulation that, paired with practices of solidarity, considers the collective over the individual, the experience over the factual knowledge. This counter-proposal accepts the possibility of failure because it does not set patterns a priori, but rather thrives from being contingent and friction-generating, leaving open the space to the unpredictable.Donna Haraway defines the politics and semiotics of articulation in contrast to those of representation in ‘The Promises of Monsters: A Regenerative Politics for Inappropriate/d Others,’ in Cultural Studies, eds. Lawrence Grossberg, Cary Nelson, Paula Treichler (New York: Routledge, 1992), pp. 295-337. Haraway explains her choice of the term articulation by way of a short etymological excursion: ‘In obsolete English, to articulate means to make terms of agreement,’ supplemented by her own, more idiosyncratic associations: ‘It is to put things together, scary things, risky things, contingent things’ (324).

To give an example of how to use art to articulate rather than represent. In discussions around participatory art, it is common to hear the following sentence: the process is much more important than the product. I do agree, of course, that the process is the fundamental part of the work. Every step of the process counts. But important for whom? And what does reaching a goal, the realisation of a product, mean? Again, using our prison theatre project as an example, when looked at from the the actors/practitioners’ point-of-view of, the performance becomes not only the end goal that brings fulfilment and satisfaction but also the possibility of a victory in terms of personal emancipation. This was apparent from interviews with them.

For the group of ex-prisoner actors who took part in our project, the realisation of the first performance of the group, Tempo Binario, had two parallel and equally important meanings: the endpoint of a path arrived at with no small effort and the possibility for ex-prisoners to emancipate themselves from their role of workshop participants.

Directed by Valentina Esposito, the performance premiered in Rome in 2015. From the performance playbill: ‘The train journey is a romantic trip, adventurous, and the landscapes crossed, most of the times, are not accessible with other transports, they seem to have something surprising. We watch them with amazement and marvel, and in a sort of enchantment they become almost immediately landscapes of remembrance and hope, of past and future. And then there are the stations, fascinating places, real and imaginary at the same time, stage of separations and expectations, escapes and returns, illusions. It is right there, between the rails of a train station who they find each other, the interpreters of Tempo binario (Binary time) free and prisoners dealing with their soul journey, experts of escape and separation, fugitives of memory, with different and difficult lives to remember. Again, now they get on the train, between the parallel rails of real and inner time, with the eyes on the window and the soul lost in the mystery of the crossed spaces. Between biography and invention, the play ponders on some of the most famous pages of Le Temps retrouvé by Proust, in the direction of a social form of theater able to represent, for the interpreters and the spectators, an instrument of emotional and intellectual rework of the fundamental knot distinguishing existence. In this case, the exploration of the memory mechanisms, the thought of the forgotten childhood, the inner perception of time in relation with the idea of death, the journey as a metaphor of existence. Important topics in a path of reflection and awareness, between identification and artistic creation.’

Conclusion: The Three A’s to Live by

To sum up, these are the three A’s I try to live by when approaching a participatory art project: Accessibility, Agency, Articulation. Creating an accessible space and making yourself accessible to others is the key to initiating the work. Leaving the space to the participants to reclaim their agency and their ownership of the process is how to strive for an equal, collaborative space. And to make a community, it is of utmost importance not to fall into the trap of representation; instead, open a collective practice of co-creation that allows everyone to speak with their own voice.In doing so it may help to ask yourself the following three questions:

Online Course

Want to delve further into the topic of this essay? Then take a look at the corresponding lesson that is part of anWant to delve further into the topic of this essay? Then take a look at the corresponding lesson that is part of an online course that consists of 10 lessons based on the 10 essays in this publication. These lessons focus on the central concepts that are treated in the essays and are followed by various questions, assignments and/or work formats.

The entire online course, including an extensive introduction, can be found via the button below. If you want to go directly to the assignments for this essay, click here.

The entire

Want to delve further into the topic of this essay? Then take a look at the corresponding lesson that is part of an online course that consists of 10 lessons based on the 10 essays in this publication. These lessons focus on the central concepts that are treated in the essays and are followed by various questions, assignments and/or work formats.

The entire online course, including an extensive introduction, can be found via the button below. If you want to go directly to the assignments for this essay, click here.