Art, Design and Architectural Practices Beyond Precarious Working and Living Conditions

Bianca Elzenbaumer

Keywords:

precarity, community economies, interdependence, commons, infrastructures

Introduction

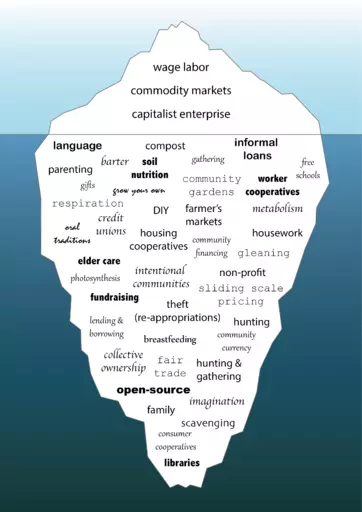

Overwork, underpay, hyper-flexibility, stretches of time without income, no sick pay, no parental leave, no paid vacation, a lack of predictability, unstable housing situations: these conditions are just the tip of the iceberg in terms of the precarious working and living conditions for people working in the fields of art, design and architecture. These circumstances are not always all present, nor are they experienced to the same degree by every person within these fields. However, they have become pretty much ubiquitous and are wearing people down, despite their love for their work. Combined with historically rooted systems of oppression, such as racism and sexism, a climate emergency, rapid biodiversity loss and a global pandemic, these destabilising and anxiety-inducing working conditions call us to engage in revolutionary ways of thinking and acting.This is a revolutionary call, which, to my mind, seems especially addressed to people like my peers and me who work in the fields of art, design and architecture. We have been trained in practical and conceptual skills that create, reinforce and also transform social and material imaginaries. However, when confronted by the pressure and anxieties produced by precarity, doing work that challenges the status quo often seems a utopian basis on which to secure one’s immediate livelihood. But to be a realist today, we need to be utopian. That is to say, in an age of social and ecological breakdown fuelled by neoliberal politics that attempts to commodify everything, we need to utilise all our desires, energies and resources to build just and sustainable futures so we do not completely destroy the very ecological basis sustaining life.

In this essay, I want to share the most important things I have learned as a designer who works to create collective modes of working and living. Ultimately, that work aims to facilitate the creation of economies, support structures and modes of life that can move artists, designers and others beyond precarity. I will outline four general principles for orientation that have become fundamental to me and my design collective, Brave New Alps, in orienting our work and lives. Moreover, I will share three concrete, everyday strategies and tactics that I have found to be supportive in creating the socio-material conditions necessary for a world guided by the principles of eco-social justice.

Principles of Orientation to Move Beyond the Hamster Wheel of Precarity

To ask how to undo, go beyond, or exit precarity is also to ask what desires, interests and values orient our actions and our being in the world. For designers, artists and architects, questions about how to go beyond precarity are also questions of how not to be governed by precarising principles, objectives, and procedures.Michel Foucault, ‘What Is Critique?’ in The Politics of Truth, eds. Sylvère Lotringer and Lysa Hochroth, trans. Lysa Hochroth (New York: Semiotext(e), 1997), pp. 23–82.

Massimo De Angelis, The Beginning of History: Value Struggles and Global Capital (London: Pluto Press, 2007).

In being informed by such questions and trying to exit precarising value practices, I propose four principles of orientation that my collective has found helpful in challenging precarity and creating support structures that can aid us in moving beyond socially and ecologically detrimental modes of being on this planet. To move beyond systemic precarity, it is incredibly important to recognise precarising patterns of work and life, as this enables the mobilisation of our skills as designers, artists and architects to invent other ways of doing. It also generates a sense of empowerment that goes beyond oneself: changing the way I work and live will not just help to de-precarise myself but also others, while simultaneously helping me to look at the world from different angles.

First Orientation Principle: Follow a Logic of Interdependence to Practise Differently

A helpful first step in learning and activating de-precarising value practices is to recognise our interdependence with others within and beyond our professional field. From this recognition, we can start to act with an ethics of care, i.e., an ethics that ‘implies reaching out to something other than the self,’Bernice Fisher and Joan C. Tronto, ‘Toward a Feminist Theory of Care,’ in Circles of Care: Work and Identity in Women’s Lives, eds. Emily K. Abel and Margaret K. Nelson (State University of New York Press, 1990), p. 102.

Fisher and Tronto 1990, p. 40.

Such value practices can take pretty conventional forms, such as fair pay for collaborators, charging properly for our services to avoid fee dumping, taking time to contribute to eco-social causes, and slowing down and cultivating a way of life that is aware of our interdependence with the more-than-human others, such as animals, plant, bacteria and fungi. We are intimately entangled in this world with these, and we cannot simply treat them as resources at our disposal or an ‘other’ onto which we offload the negative externalities of our activities.

Acting from a logic of interdependence and solidarity contributes—one act at a time—to improving the working situation and ability to produce transformative work for many others more than just oneself. Besides the conventional forms already mentioned, this logic of interdependence in my own work takes the form of making social, physical and economic spaces for younger practitioners from multiple fields, such as design, agro-ecology and social work, so that they can develop engaged, caring and transformative practices. It also involves taking time to share as much knowledge as possible to support other practitioners in strengthening their critical work. But it also means asking for help and being honest about issues I struggle with myself.

Second Orientation Principle: Treat the Economy as the Malleable Stuff of Everyday Life

Another empowering move in generating de-precarising value practices is to learn to see the economy as always diverse—i.e., as always consisting of activities and exchanges beyond the money nexus and the logic of profit, and thus as a realm we always participate in, no matter how we secure our livelihoods. To better grasp the concept of the diverse economy, we can imagine the economy to have the shape of an iceberg, where market exchanges are only the tip of what we see. Under the water, there is a diversity of relational patterns of exchange and support that help people to sustain their livelihoods (see figure 1).On the one hand, this approach to the economy, which was developed by feminist geographer J. K. Gibson-Graham,

J.K. Gibson-Graham, The End of Capitalism (As We Knew It) (Minneapolis/London: University of Minnesota Press, 2006); J.K. Gibson-Graham, Jenny Cameron, and Stephen Healy, Take Back the Economy: An Ethical Guide for Transforming Our Communities (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013).

Michel Callon, ‘What Does It Mean to Say That Economics Is Performative?’ in Do Economists Make Markets: On the Performativity of Economics, eds. Donald MacKenzie, Fabian Muniesa, and Lucia Sui (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007), pp. 311–57; Timothy Mitchell, ‘Rethinking Economy,’ Geoforum 39, no. 3 (2008): pp. 1116-1121.

This move towards diverse economies is especially important because (very often) critical, transformative work pays less and is more difficult to sustain than work that perpetuates hegemonic systems. In a diverse economies logic, making a living ceases to be a question of working your way up a ladder with bars that have become ever further apart and ever more slippery. Rather, it becomes a matter of weaving yourself into an ecology of practices—i.e., a meshwork of practices that support each other, which enables you to unleash your own force in challenging the status quo and experimenting with other ways of doing.

Isabelle Stengers, ‘Introductory Notes on an Ecology of Practices,’ Cultural Studies Review 11, no. 1 (2005): pp. 183-196, dx.doi.org/10.5130/csr.v11i1.3459.

In my own practice, this principle has let me focus my energies on the collective creation of common physical spaces in which economies are cultivated that have, at their core, the well-being of people, the earth, and others. One such space is a community academy called La Foresta. It was set up through collaborative efforts at the train station of the area I live in, where the local community is invited in to experience the generative force of non-monetary exchanges, of production processes that are not driven by efficiency, and of ways of life that do not conform to consumerist culture.

Third Orientation Principle: Undo Ambitions for Imperial Modes of Living

In addressing our desires for less precarious ways of working and living, we need to engage with structural and personal ties to imperial modes of living—i.e., modes of life that draw on ecological and social resources of faraway places to guarantee high living standards for oneself, while destroying others’ habitats and ways of life.Ulrich Brand and Markus Wissen, ‘Imperial Mode of Living,’ Krisis Journal for Contemporary Philosophy, no. 2 (2018): pp. 75–78.

In the early 1990s, Bangladeshi photographer Shahidul Alam proposed the terms majority and minority worlds to replace the disempowering ‘third world.’ In this categorisation, ‘minority world’ refers to that fraction of humankind that is relatively well off (see Russell Leong, ‘Majority World: New Veterans of Globalization,’ Amerasia Journal 34, no. 1 (2008): vii–xii).

Kathryn Yusoff, A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2018).

Once these dividing and destructive patterns become apparent, it is possible to begin to form ambitions—and from these to produce projects and, consequently, modes of living—that empower through the creation of social solidarity and material support structures that allow for the emergence of a just pluriverse. In my own practice, the attempts to undo imperial modes of life are about building a practice in which there is no longer place for jetting around the world by plane, but also about learning from and championing practices that are marginalised in mainstream discourse because they are seen as too ecological, social, feminist, or queer. This means a lot of questioning of myself and the structures I am part of, while trying to change what I take for granted and finding ways to restructure or abandon destructive practices.

Fourth Orientation Principle: Construct Nurturing Value Practices

Combining a logic of interdependence and diverse economies with a desire to undo imperial modes of living means being at a point where it’s possible to stop trying to fit one’s work and life into conventional business or career templates. As J. K. Gibson-Graham teaches us, the economies that sustain our livelihoods are, by default, always much more diverse—and I would say messy—than we are made to think.It’s also interesting to note that when you start digging into design practices that are successful in conventional terms, these very often sustain themselves in part through inherited wealth and/or supportive governments. These governments have themselves mostly built their wealth on colonial pasts, a neocolonial present and petroleum extraction.

The Feral Business Research Network, of which I am a member, draws together a whole range of practitioners who are enacting diverse economies through artistic and designerly methods.

Strategies and Tactics to Move Beyond Precarity

If you have come this far in reading this text, you might begin to argue that the challenge set out is too big and that conventional, competitive ways of practising art, design and architecture still seem the safest option to go beyond precarity. If this is the case, you might be experiencing a form of the‘cruel optimism’ that affect theorist Lauren Berlant has so sharply theorised.

Lauren Berlant, Cruel Optimism (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011).

First Strategy and Tactic: Make Long-term Plans

Capital moves people around and draws them to its centre: to find your luck, you are urged to move from the village to the town, from the town to the regional capital, and from there to the metropolis. The constant urge to move on—and particularly to move ever closer to a more powerful centre—is, in our view, a precarising value practice that is further exacerbated by the fact that places where capital is denser are very often also places that precarise through exclusivity (expressed through, for example, high living costs and fierce restrictions on the right to stay based on qualifications and citizenship), and sped up, individualising lifestyles. We know very well that the centre is also often where you get fresh air (and safety) by escaping the stifling patriarchal, sexist, racist and homophobic structures of more peripheral spaces, or where there is at least a chance of finding paid work (or security from war), but we have also observed that resisting capital’s demand for constant movement is a strategy against precarisation for some artists, designers and architects.We have seen that places that feel more peripheral are often more fertile spaces for growing de-precarising value practices because access to living and working space is more affordable, but we also think that whether you choose to live in a space that feels central or peripheral (and this can be a pretty subjective feeling), what is most important in terms of challenging precarity is to have a long-term plan you can stick to. For example, committing to living in one specific place or working with one specific transformative topic, and inventively organising to stick to the plan when the pressures, anxieties, and doubts of precarity pull on you. In my own case, my passion for socially and ecologically just economies let me choose commons as a focus point for my work 11 years ago, while my longing for the mountains I grew up in has let me choose a rural area in the Italian Alps as my space for life and work six years ago.

Second Strategy and Tactic: Loosen the Grip of Money

Precarity is also related to the need for a constant flow of money to cover basic needs, work-related expenses and leisure. However, the more you earn, the more you spend, so the feeling of never earning enough remains pretty much a constant. From observing this dynamic, we have becomeconvinced that voluntarily frugal lifestyles—paired with the political request for an unconditional basic income

An unconditional basic income is a regular financial grant paid by the government to all citizens, whether they have a paid job or not.

Common Wallet, ‘How to cultivate an empowering relation to money?’ Interview by Bianca Elzenbaumer and Martina Dandolo, July 2020, www.magari.jetzt/coordinate-rigeneranti/.

Such experiments can lead to more common plans, such as with the case of a group of peace activists—one of whom is the architect Luca Rigoni—who started a similar income-sharing collective in Fidenza, Italy, in the 1990s. Ten years later, they opened up their experiment to more people and built an ecological co-housing space in their town, which also offers leisure spaces for others in their neighbourhood.

‘Ecosol Fidenza—cohousing nel quartiere Europa a Fidenza,’ accessed July 25, 2019, www.ecosol-fidenza.it/.

Caroline Shenaz Hossein, The Black Social Economy in the Americas: Exploring Diverse Community-Based Markets (Perspectives from Social Economics) (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018).

Third Strategy and Tactic: Care for Common Infrastructures

Safe housing is a basic need, but desires for its fulfilment are often channelled into efforts for single household and family homes, and often come with precarising mortgages and individualisation by design. Moving desires and efforts around housing towards cooperative living can be very empowering, and, for designers wanting to do critical and transformative work, a way to embed themselves into spaces where daily experimentation opens different approaches to what designs and human practices the world beyond precarity needs. To share ownership of a building keeps living costs relatively low in the long-run, while providing communal spaces in which to grow supporting social connections that can carry people through financially difficult times. It is also a way to offer support for people in immediate need for shelter and care.Recent examples of such solidarity in our own network are the Cornerstone Housing Coop in Leeds, England, which always offers one spare room to refugees in need of immediate accommodation, and R50 in Berlin, Germany, who hosted a family of twelve Syrian refugees between 2015 and 2016 until they had found proper housing for all of them through their network.

Very often, such forms of cooperative living can also be inscribed into what we would call intergenerational commons—i.e., commons that are passed on between generations. This is because land and houses can be locked into communal ownership for perpetuity through legal forms, such as community land trusts and network arrangements between cooperatives owning property, thus guaranteeing a base for critical citizenship and work for generations to come.

See the network of radical cooperatives Radical Routes in the UK and the radical housing network Mietshäuser Syndikat in Germany, which leverage their collective power to protect and expand the possibilities for egalitarian and affordable access to property for living and working.

Bianca Elzenbaumer and Fabio Franz, ‘Footprint: A Radical Workers Co-Operative and Its Ecology of Mutual Support,’ Ephemera: Theory and Politics in Organization 18, no. 4 (2018): pp. 791-804.

But clearly, common infrastructure is not just about housing. To start small and immediately with caring for more collective infrastructures, you can investigate how others can be empowered through the social, intellectual, and/or material wealth you have through practice. How can it be channelled into more collective and collaborative efforts to work ourselves away from precarious living and working conditions towards an ecologically and socially just society? Small experiments in opening what you have up to others can bring up desires and ideas for more extensive action.

The frame here is about creating ecologies of support where the myth of the heroic designer and artist as genius is undone in favour of gentle, solidary and effective modes of cooperation that enable transformative infrastructures to emerge.

Taking Action

As you see, these entry points into value practices that defy precarity interweave with and nurture each other. It might even be practices that you are also already engaged in, maybe more out of necessity than free will. But what if those practices you cultivate were not just temporary fixes but the seeds for more ecologically and socially just futures? For artists, designers and architects, tackling their own issues around precarious work and life through collaborative and cooperative arrangements—starting today wherever they are at—is a way to enact a prefigurative politics.This is a politics that does away with the separation between life and work in collectively empowering ways, rather than the disempowering ones enacted by neoliberal politics, which sacrifices all life for work and hegemonic notions of success. Combine these practices that challenge precarity through the creation of social and material support structures with social movement activism—for causes such as environmental justice, queer culture, no borders, universal healthcare, and a basic income—and you get a powerful mix of activities that aim to take us en masse beyond precarity.

Online Course

Want to delve further into the topic of this essay? Then take a look at the corresponding lesson that is part of anWant to delve further into the topic of this essay? Then take a look at the corresponding lesson that is part of an online course that consists of 10 lessons based on the 10 essays in this publication. These lessons focus on the central concepts that are treated in the essays and are followed by various questions, assignments and/or work formats.

The entire online course, including an extensive introduction, can be found via the button below. If you want to go directly to the assignments for this essay, click here.

The entire

Want to delve further into the topic of this essay? Then take a look at the corresponding lesson that is part of an online course that consists of 10 lessons based on the 10 essays in this publication. These lessons focus on the central concepts that are treated in the essays and are followed by various questions, assignments and/or work formats.

The entire online course, including an extensive introduction, can be found via the button below. If you want to go directly to the assignments for this essay, click here.

Overwork, underpay, hyper-flexibility, stretches of time without income, no sick pay, no parental leave, no paid vacation, a lack of predictability, unstable housing situations: these conditions are just the tip of the iceberg in terms of the precarious working and living conditions for people working in the fields of art, design and architecture. These circumstances are not always all present, nor are they experienced to the same degree by every person within these fields. However, they have become pretty much ubiquitous and are wearing people down, despite their love for their work. Combined with historically rooted systems of oppression, such as racism and sexism, a climate emergency, rapid biodiversity loss and a global pandemic, these destabilising and anxiety-inducing working conditions call us to engage in revolutionary ways of thinking and acting.

This is a revolutionary call, which, to my mind, seems especially addressed to people like my peers and me who work in the fields of art, design and architecture. We have been trained in practical and conceptual skills that create, reinforce and also transform social and material imaginaries. However, when confronted by the pressure and anxieties produced by precarity, doing work that challenges the status quo often seems a utopian basis on which to secure one’s immediate livelihood. But to be a realist today, we need to be utopian. That is to say, in an age of social and ecological breakdown fuelled by neoliberal politics that attempts to commodify everything, we need to utilise all our desires, energies and resources to build just and sustainable futures so we do not completely destroy the very ecological basis sustaining life.

In this essay, I want to share the most important things I have learned as a designer who works to create collective modes of working and living. Ultimately, that work aims to facilitate the creation of economies, support structures and modes of life that can move artists, designers and others beyond precarity. I will outline four general principles for orientation that have become fundamental to me and my design collective, Brave New Alps, in orienting our work and lives. Moreover, I will share three concrete, everyday strategies and tactics that I have found to be supportive in creating the socio-material conditions necessary for a world guided by the principles of eco-social justice.