Soft Histories

interview with Jeanine van Berkel

interview by Rana Ghavami – 29 nov. 2022topic: Bodies and Breath: Embodied Research & Writing

In My Body is a house, Jeanine van Berkel’s prose move us from inside her mouth to the core, along dust and bones, listening to memories and silences as they slip between dreams, inherited histories, and imagination. In this interview, we spoke with her on how she engages embodied research and writing through the material she makes, the readings she holds, and the intimate spaces she invites us to. Jeanine van Berkel is a graphic designer, visual researcher and writer.

Mama couldn’t talk for ten years after we left the island. She left all her words behind because there was nothing left to say

sometimes grief is slow like that

sometimes grief is slow like that

In this series we engage designers, makers, artists, writers in conversations about the role of embodied research and writing in their practices, in their hybrid states of making, doing and living. These conversations unfold through a series of writings, workshops and performances, which we are publishing on our website.

In this first contribution, Jeanine van Berkel’s prose moves us from inside her mouth to the core, along dust and bones, listening to memories and silences as they slip between dreams, inherited histories, and imagination. We spoke to her about how her body houses her urge to listen to 'archival silences', memories residing within herself, and the (un)known histories of her motherlands. We asked her how she sees her ongoing work—the workshop Soft histories and this text My body is a house—as part of an ongoing research to shape these silences (of soft histories) through words, materials, pauses, readings, workshops, and installations.

In this first contribution, Jeanine van Berkel’s prose moves us from inside her mouth to the core, along dust and bones, listening to memories and silences as they slip between dreams, inherited histories, and imagination. We spoke to her about how her body houses her urge to listen to 'archival silences', memories residing within herself, and the (un)known histories of her motherlands. We asked her how she sees her ongoing work—the workshop Soft histories and this text My body is a house—as part of an ongoing research to shape these silences (of soft histories) through words, materials, pauses, readings, workshops, and installations.

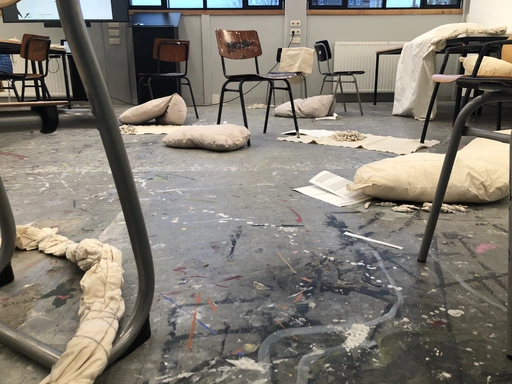

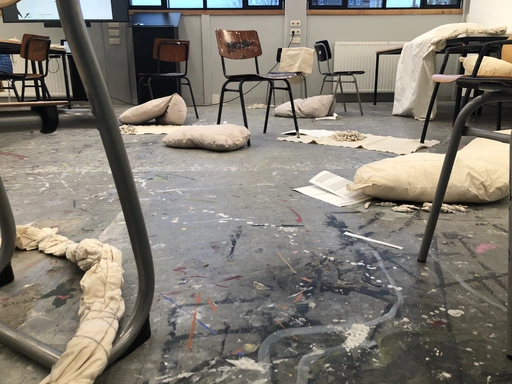

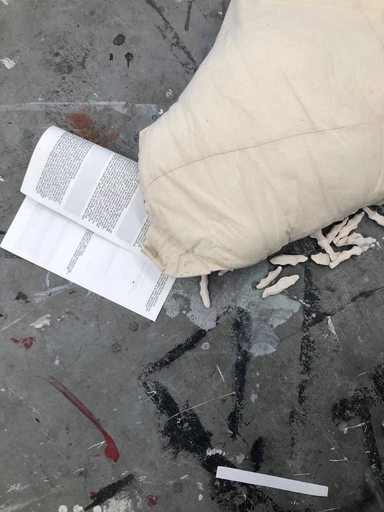

Last year in November we got to know each other at the embodied writing workshop Soft Histories, which you led with our invitation. That day you transformed the classroom by installing fragments of your work—the ceramics, the text, the reader you had made for us, the sound, the embodied exercises, the photographs. You and the whole space invited us to be present together. Your reading, the reader, the ceramic objects, and the memories you shared with us expanded my experience of reading this text. How do you care for this relation between your writing, the text, and the way we encounter your work?

With the set-up of a space I want to invite the audience into the experience of my performance. I want people to feel comfortable while listening. I try to do this through softer seating, like cushions, fabrics and foam, but also, through the sonic experience of the ceramic objects. My other reason is definitely to make myself feel comfortable. I talk about difficult, sometimes even painful topics, and I want to do this inside a space where I feel I can share that.

Even though my research is based in writing, I’m still a designer/visual artist at heart. I think making time to set up a space or to design a booklet is also a way to show that I care for my texts, ceramic objects, the audience and myself.

Even though my research is based in writing, I’m still a designer/visual artist at heart. I think making time to set up a space or to design a booklet is also a way to show that I care for my texts, ceramic objects, the audience and myself.

What does your work mean to you? Here I want to bring together the relation between a form and the particular meaning it has for the maker as they make one another.

My work is a way to talk, to feel, to relate, to remember. As a woman of color, I have felt voiceless and out of place. Sometimes I still feel like this. Throughout my work I explore and commit myself to this feeling of not belonging. It helps me to grasp my thoughts and find ways to express them. In a way it is really personal as I look closely to this internal storm that’s going on in my body. However, my work has also helped me to have certain conversations that needed to be held a long time ago. And that’s okay; sometimes the time is not there yet. This is something I have come to understand through my practice.

My work is about the story I wanted to hear as a child but didn’t encounter because of particular circumstances like growing up in a white family, town, and country. By writing, making and speaking on this, I noticed how some people can relate to this as well, and this connection is what I have been yearning for so many years.

My work is about the story I wanted to hear as a child but didn’t encounter because of particular circumstances like growing up in a white family, town, and country. By writing, making and speaking on this, I noticed how some people can relate to this as well, and this connection is what I have been yearning for so many years.

And soft histories?

The first text I ever wrote through this research was called Soft Histories and it started like this:

History is based on facts.

Facts that can be traced back.

But what about all the unspoken facts – the untraceable facts.

The facts you know by oral transmission.

The facts you know by feeling.

I still come back to this first paragraph as a reminder of where the root of my research lays. These questions resonate with me on a personal level, but also more broadly, in terms of the relationship Curaçao has with The Netherlands. With this paragraph, I began my ongoing research. All the various projects I do – from this text, to the workshop, to installations – are iterations of Soft Histories.

The word “history” alone doesn’t cover what I want to talk about. Yes, history is important and does play a big part in my research but I wanted to look to the softer side of history. The side that is forgotten, vague, silenced and not coherent. I want to place importance on these things because I feel that non-factual knowledge is devalued here in the West, even though so many people like myself are yearning for the soft histories. In the end, the idea of Soft Histories came from a place of absence.

I still come back to this first paragraph as a reminder of where the root of my research lays. These questions resonate with me on a personal level, but also more broadly, in terms of the relationship Curaçao has with The Netherlands. With this paragraph, I began my ongoing research. All the various projects I do – from this text, to the workshop, to installations – are iterations of Soft Histories.

The word “history” alone doesn’t cover what I want to talk about. Yes, history is important and does play a big part in my research but I wanted to look to the softer side of history. The side that is forgotten, vague, silenced and not coherent. I want to place importance on these things because I feel that non-factual knowledge is devalued here in the West, even though so many people like myself are yearning for the soft histories. In the end, the idea of Soft Histories came from a place of absence.

Can you speak on how you transform a reader’s or listener’s experience of time in your writing–through the rhythm, its cadence and duration, the hesitations, the pauses, the gaps, the erasures?

Silences and pauses carry meaning.

This makes me dream.

Mystify my history.

It gives me the freedom to fill in the blank spaces.

Construct my own story.

Fantasize about my identity – about my rootlessness.

Maybe I’m from nowhere.

Maybe I’m from everywhere.

Sometimes I also don’t know what happens between the lines, or inside a silence. Sometimes I also don’t have any words, not even an imaginative story to fill in the gaps. Sometimes I’m just empty and tired. And I think it’s okay to add that into a story.

I also want to leave actual, physical space in my texts. This is a way for myself to take time while performing, but it’s also a way to show that there is more even though you can’t see it. Sometimes there is just nothing left to say; what happens then? I’m still thinking about what sits inside silence.

Silence sometimes feels likes a heavy pressure on my chest and sometimes it just feels like an endless nothingness. Sometimes it’s really hard to think about it and I react with the emotion of being sad or frustrated. Other times there is just no feeling as if everything is flat. In these times there’s literally nothing. That’s why silence is so interesting to me. It can take so many different forms in the sense of how it feels to what it looks like on a page, in a space, or in the body.

Sometimes I also don’t know what happens between the lines, or inside a silence. Sometimes I also don’t have any words, not even an imaginative story to fill in the gaps. Sometimes I’m just empty and tired. And I think it’s okay to add that into a story.

I also want to leave actual, physical space in my texts. This is a way for myself to take time while performing, but it’s also a way to show that there is more even though you can’t see it. Sometimes there is just nothing left to say; what happens then? I’m still thinking about what sits inside silence.

Silence sometimes feels likes a heavy pressure on my chest and sometimes it just feels like an endless nothingness. Sometimes it’s really hard to think about it and I react with the emotion of being sad or frustrated. Other times there is just no feeling as if everything is flat. In these times there’s literally nothing. That’s why silence is so interesting to me. It can take so many different forms in the sense of how it feels to what it looks like on a page, in a space, or in the body.

In the text, you move from intimate crevices, bodies, to shimmering objects, and the depths of the seas. The places you take us fall somewhere between fiction, facts and imagination. Can you speak on this?

These movements are made in relation to my personal story and how much I want to share. It’s about how much I tell and don’t tell. Using surrealistic or even imaginary places gives me a form of protection. The people that know me will know what I’m talking about and others will read the texts in a different way through a different interpretation or different connection to the topic. I love the moment after a performance reading when somebody comes up to me and shares how they connected to the reading. I remember somebody telling me about their American-Filipino history. It’s a very different context, but still there was common ground to connect and share the experience of carrying a history inside your body.

Sometimes I’m not ready yet to share certain details because it’s still too painful to say it out loud or to write it down. So I keep it inside, until I can’t hold it in anymore and I have to say it because keeping it for myself also hurts. It’s a paradox, haha. For me there’s a difference between words that are written down and words that are spoken. I find that writing in my research gives me more space and time to think. I can edit a memory until it’s mine or until it’s not mine anymore. Maybe it was never mine in the first place.

Other times, I wonder if it’s my story to tell or not. My mom plays a big part in almost all of my stories. I’m trying to be aware of when it’s my time to tell something or not. All these moves are based on feeling. When does it feel right to share or not to share?

Sometimes I’m not ready yet to share certain details because it’s still too painful to say it out loud or to write it down. So I keep it inside, until I can’t hold it in anymore and I have to say it because keeping it for myself also hurts. It’s a paradox, haha. For me there’s a difference between words that are written down and words that are spoken. I find that writing in my research gives me more space and time to think. I can edit a memory until it’s mine or until it’s not mine anymore. Maybe it was never mine in the first place.

Other times, I wonder if it’s my story to tell or not. My mom plays a big part in almost all of my stories. I’m trying to be aware of when it’s my time to tell something or not. All these moves are based on feeling. When does it feel right to share or not to share?

During the workshop as well as in this text you have cited the work of Carmen Maria Machado and Saidiya Hartman. Citing practices are lineages. How have you encountered these works?

I keep coming back to these amazing writers, for different reasons, but both as examples of how they tell such personal stories in an honest and beautiful way. Saidiya Hartman talks more about the restless feeling of not belonging to a country that you ended up in. She does this by searching for answers in the country of probable heritance, even though she doesn’t know for sure because of how her history has been wiped out by the slave trade, and by going through archives and being met by silences, gaps and dead ends. Carmen Maria Machado, on the other hand, tells her painful experience of an abusive queer relationship by using a very interesting framework in her book In the Dream House. She uses fairly short chapters to show different fragments of a story, her story actually.

Through their stories, I’ve learned about various ways of writing. I often go back to read parts of their books when I need a reminder of how I would like to write. I admire their writing a lot. I always recommend their texts and books. I think it’s important to share their writing as a different kind of thinking: a way that’s also possible and just as valuable.

I came across In the Dream House in my favorite bookstore in Arnhem, Walter Bookstore. I enjoy buying books that just appeal to me by their cover… I’m still a graphic designer, haha.

The text by Saidiya Hartman was recommend to me when I started my Masters and talked about the topic I wanted to research. Her texts have been really helpful, especially in the way they remind me that I’m not wandering alone in the in-between.

Through their stories, I’ve learned about various ways of writing. I often go back to read parts of their books when I need a reminder of how I would like to write. I admire their writing a lot. I always recommend their texts and books. I think it’s important to share their writing as a different kind of thinking: a way that’s also possible and just as valuable.

I came across In the Dream House in my favorite bookstore in Arnhem, Walter Bookstore. I enjoy buying books that just appeal to me by their cover… I’m still a graphic designer, haha.

The text by Saidiya Hartman was recommend to me when I started my Masters and talked about the topic I wanted to research. Her texts have been really helpful, especially in the way they remind me that I’m not wandering alone in the in-between.

You studied graphic design at ArtEZ, and graduated in2021 from the Critical Studies programme at Sandberg Instituut. How have you developed your approach to research, writing and making? And how has that changed over the years?

This is a really interesting question and something I think about a lot lately as my experiences were really different in both schools. At ArtEZ I experienced the assignments as relatively quick and high paced even though there was this wish from myself to do in-depth research. In my graduation year, I had finally enough time to go deeper into research I really wanted to do which I thought was so exciting. In this year we had to write our thesis, do a practical assignment and do our own research project. It all started here for me because this was the first time I could research a topic for a few months while having enough time to read, write, and do visual experiments. It was then that I explored how I could truly implement my theoretical research into my visual practice. This has exactly become the way I like to work.

When I started at the Sandberg Instituut, I had learned the ways and the tools for my practice but I didn’t want to continue the research I had done at ArtEZ. Even though, after finishing my Masters, I still see connections between what I make, and the way I do research now. At ArtEZ I wrote a thesis where I played with adding memories to a fairly academic text. This is something I still do, even though the ratio is different.

Of course, a lot has changed as well. At the end of my Bachelors at ArtEZ, I was out of touch with what I enjoyed making, doing, researching, or reading. I even thought I would never design again. Graphic design wasn’t even fun for me anymore. For every decision I made in a project, there needed to be a reason. In a way I get this way of making, but I don’t think this truly worked for me as a student. A good example of this was the process of designing my thesis. My first sketches where busy, and maybe a bit all over the place, but I enjoyed the design process. Because of the feedback I got from teachers, I decided to tone down the design which made the book generally more appealing (to them). Don’t get me wrong I learned a lot about how you can design a “good” book. I’ve learned the “rules” so to speak. However, was it a book of my own liking? I don’t know. During my actual graduation, our external examiner, Clara Lobregat Balaguer, asked me to show her my first designs and she said to me that they were much better. She told me that I can be wild if I want to. In a way she was the first person to remind me again of how it can be done differently. I want to give her a big shout out because I’ve learned so much from her and that moment. It’s actually ongoing, we kept in touch after my graduation at ArtEZ, and I’m still learning from her.

At the Sandberg Instituut, there was time and space to focus on a new research topic where tutors, like Mia You, stimulated my way of writing. She was my main tutor for two years, which was a unique experience for me. Every step of my research I discussed with her and I appreciate how much she encouraged me to keep writing even though sometimes I felt like I didn’t know what I was doing. Through our conversations she stimulated me to keep writing, to keep reading. She is a wonderfully kind person.

I enjoyed having this extra time during my Masters to think about what I wanted to research in the long run. Here I explored which methods of research work for me and my work, and now I am building upon those experiences, beyond these academies.

When I started at the Sandberg Instituut, I had learned the ways and the tools for my practice but I didn’t want to continue the research I had done at ArtEZ. Even though, after finishing my Masters, I still see connections between what I make, and the way I do research now. At ArtEZ I wrote a thesis where I played with adding memories to a fairly academic text. This is something I still do, even though the ratio is different.

Of course, a lot has changed as well. At the end of my Bachelors at ArtEZ, I was out of touch with what I enjoyed making, doing, researching, or reading. I even thought I would never design again. Graphic design wasn’t even fun for me anymore. For every decision I made in a project, there needed to be a reason. In a way I get this way of making, but I don’t think this truly worked for me as a student. A good example of this was the process of designing my thesis. My first sketches where busy, and maybe a bit all over the place, but I enjoyed the design process. Because of the feedback I got from teachers, I decided to tone down the design which made the book generally more appealing (to them). Don’t get me wrong I learned a lot about how you can design a “good” book. I’ve learned the “rules” so to speak. However, was it a book of my own liking? I don’t know. During my actual graduation, our external examiner, Clara Lobregat Balaguer, asked me to show her my first designs and she said to me that they were much better. She told me that I can be wild if I want to. In a way she was the first person to remind me again of how it can be done differently. I want to give her a big shout out because I’ve learned so much from her and that moment. It’s actually ongoing, we kept in touch after my graduation at ArtEZ, and I’m still learning from her.

At the Sandberg Instituut, there was time and space to focus on a new research topic where tutors, like Mia You, stimulated my way of writing. She was my main tutor for two years, which was a unique experience for me. Every step of my research I discussed with her and I appreciate how much she encouraged me to keep writing even though sometimes I felt like I didn’t know what I was doing. Through our conversations she stimulated me to keep writing, to keep reading. She is a wonderfully kind person.

I enjoyed having this extra time during my Masters to think about what I wanted to research in the long run. Here I explored which methods of research work for me and my work, and now I am building upon those experiences, beyond these academies.

Research, writing and making happens across time and in different spaces. It takes time for things to materialise. I often come across this unfortunate phrase that time spent on not making is time spent on being ‘in your head’. How do you value the time in-between tangible making?

I think almost all of us have experienced that feeling of being stuck, of not knowing what to do next. Over the years, I think I have developed two methods. One is to take a break. I try to rest for a little bit, for a couple of days or even a few hours. In those moments I try to be kind to myself. It’s okay to not always know what you want to do, or to not produce texts or works. It’s okay to watch some brainless tv, lay on the couch, or read a fun story, cook an elaborate dinner, take a walk, sit down in the sun, or listen to some music, it all is really okay. I have to say that I do this mainly when I’m in between projects or iterations of a process.

The other method I use is when I am at the beginning phase of a project or when a deadline is approaching, and this one is quite the opposite of the first one. But I like to sit with the work. I like to make actual hours with staring at my screen, rereading some of my go-to-texts, doing small writing exercises, writing down parts of sentences that pop-up in my head, making some sketches. And again, I try to be kind to myself in this state. It’s okay if I don’t have a clue right away. It’s okay if I get frustrated and throw out the initial ideas. It’s all okay.

The other method I use is when I am at the beginning phase of a project or when a deadline is approaching, and this one is quite the opposite of the first one. But I like to sit with the work. I like to make actual hours with staring at my screen, rereading some of my go-to-texts, doing small writing exercises, writing down parts of sentences that pop-up in my head, making some sketches. And again, I try to be kind to myself in this state. It’s okay if I don’t have a clue right away. It’s okay if I get frustrated and throw out the initial ideas. It’s all okay.

In one of our conversations we spoke about how methods and processes are taught in art education, and how they shape creative processes: what we think is possible, the form that our work takes, the formats that are envisioned. What happens when the story you want to tell, cannot be transformed and shared through these methods? Can you share how you’ve slowly shaped your own process and a space for yourself?

To be honest, I’m still learning to trust my creative process and practice. It’s not easy but these two extra years at the Sandberg Instituut have really helped me. Several tutors from my department like Mia You, Simone Zeefuik and belit sag, stimulated me to continue with this research. There were also people outside of the department who have helped me to gain confidence again like Judith Leysner and Tracian Meikle from Unsettling, and Nagaré Willemsen from the USB – Black Student Union. They listened and were kind to me, and they gave me helpful input to develop my ideas over time.

Besides this mutual support and care, I want and try to get in touch with my feelings. Maybe this sounds a bit corny, but I do think it’s important to listen to this gut feeling because it has helped me to regain this playfulness in the way I work. I’m still thinking through what feels right and good to me and my process. This comes from the desire to enjoy my practice again. This means that sometimes there is no logical explanation yet. Just something that I want to try, and by trying I see if it works inside my research.

Besides this mutual support and care, I want and try to get in touch with my feelings. Maybe this sounds a bit corny, but I do think it’s important to listen to this gut feeling because it has helped me to regain this playfulness in the way I work. I’m still thinking through what feels right and good to me and my process. This comes from the desire to enjoy my practice again. This means that sometimes there is no logical explanation yet. Just something that I want to try, and by trying I see if it works inside my research.

This comes from the desire to enjoy my practice again. This means that sometimes there is no logical explanation yet. Just something that I want to try, and by trying I see if it works inside my research.