Power, the body and a mosquito swarm

How I ended up making art about the most hated insect in the world.

blog by Vivian Caccuri – 25 mei 2022topic: Body and power(lessness)

For the Brazilian composer and sound artist Vivian Caccuri, the sound of the many mosquitoes in Brazil initiated a fascinating search for history, biology and political context. On Monday May 30, she will talk in Zwolle with students of Classical Music and Illustration Design and anyone else who wants to know more about her working method and interdisciplinary collaboration. In this blog she tells more about her work.

This blog is part of our project The Body and Power(lessness), on how we physically experience autonomy, power(lessness), (in)justice, care and collectivity.

This blog is part of our project The Body and Power(lessness), on how we physically experience autonomy, power(lessness), (in)justice, care and collectivity.

A couple of years ago, interspecies aesthetics was very trendy. Right now, it feels like part of the status quo in contemporary art, amidst many other trends. Everywhere you go in different art fields or the academic world you will find attempts at creating bonds with animals, insects, fungi and bacteria. I get it, we are so disconnected from nature in 2022 that creating a feasible or fictional aesthetic dialogue with other species feels like a little tangible utopia, between the many other utopias that are now broken, forgotten or left behind in Late Capitalism.

I live in one of the warmest cities in Brazil - Rio de Janeiro - where the largest urban forest in the world, Floresta da Tijuca, lies. In Rio, humidity makes my hair voluminous and wavy, my skin oily and all of the spaces I have lived in are somehow full of life, interspecies life. Here are some practical examples:

I live in one of the warmest cities in Brazil - Rio de Janeiro - where the largest urban forest in the world, Floresta da Tijuca, lies. In Rio, humidity makes my hair voluminous and wavy, my skin oily and all of the spaces I have lived in are somehow full of life, interspecies life. Here are some practical examples:

there’s no way of keeping bread out of the fridge in Rio, it will get moldy even before you finish eating the loaf.

leaving sugary goods, pastries, water or fruit unprotected will quickly attract an angry surge of ants.

At night, close your windows. Depending on your neighborhood, bats will fly in and eat your bananas, persimmons and mangoes (I bumped into a hungry one once) and monkeys will steal whatever they feel like stealing if you are living in their area.

Almost wherever you go, you will share the space with a mosquito. Or many mosquitoes. And that’s not a summer problem, it's an all-year-round feature and our mosquitoes can carry diseases.

So you see, the interspecies issue in Rio de Janeiro is not a choice, or an aesthetic desire. It is our tangible reality, part of our everyday life and the further North you go in Brazil, the more intense this interspecies reality is. And this is how temperature defines life in the Tropics: while the North has the challenge of having to manage the cold and the ice, we, the South, have the challenge of controlling an unstoppable movement of living beings into our residential or work environments: mold, cockroaches, monkeys, bacteria, ants, moths, flour moths, bats, termites, possums, weevils, geckos, spiders and many, many mosquitoes. It seems that these animals are here to remind us that a perfectly sterile urban environment will never be possible in the South. Who needs that anyways?

To that same extent, my experience in Lagos - Nigeria in 2017 was life-changing because I understood myself from a different position in the Global South. This new perspective made me realize mosquitoes are indeed a fascinating subject for art and a great way to bully a curator and a museum director. In this video I explain how it all started:

To that same extent, my experience in Lagos - Nigeria in 2017 was life-changing because I understood myself from a different position in the Global South. This new perspective made me realize mosquitoes are indeed a fascinating subject for art and a great way to bully a curator and a museum director. In this video I explain how it all started:

The ugliest sound in nature

Mosquitoes are very compelling to me, especially because of their horrible sound. I have also been to Ghana, India, and the Brazilian Amazon and even in these equatorial regions, the mosquito sound is far from being appreciated by the local population.

You know the buzz of a mosquito in your ear? Imagine that, but with the sound of grief. People crying or complaining, or staffers scolding prisoners … that’s all there was to hear most of the time.

This is exactly the kind of sound that is worth working with as an art project. Sounds that are put very low in the hierarchies of beauty, balance and harmony, sounds that are forbidden, fought against, ridiculed or made jokes of. Accordingly, most of my sound works are about specific marginalized sounds, soundscapes, undesired sensations, acoustic behaviour or musical instruments. These are some examples:

1. I proposed an eight-hour silent walk with twenty other people where we listened to all kinds of sounds in different locations of cities all over the world. Most of which are considered unimportant, trivial or ugly.

2. I simulated the destruction of a sound system, just like the government does all over Brazil, but in the middle of a street party:

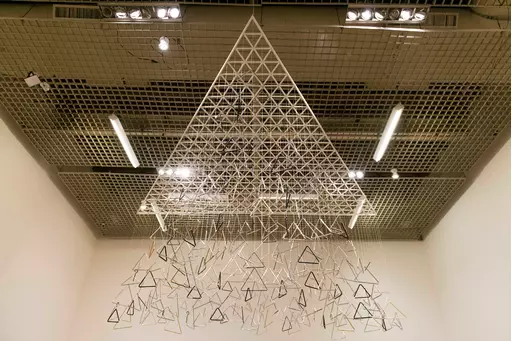

3. The triangle, the object of ridicule in an orchestra, became the main instrument of this installation at Pinacoteca de São Paulo and a series of performances.

The opposite of birds

Low-status sounds are extremely interesting to me especially because they reveal aspects of power and dominance in different societies and periods. That is no different with mosquitoes. They are to me the exact opposite of birds. Birds, especially in Western cultures, are singing teachers, they are aesthetic references for voice projection in space, an ideal of natural beauty and represent pure, unassisted, and celestial connection to the environment.

How different they are from mosquitoes! Just like water and oil! These evil insects have no sense of rhythm, tone, silence or beauty. Contrary to birds, mosquitoes emit a sound that is the result of their wings resonating in their external skeleton, it is like the soulless noise made by an annoying machine, not worth listening to, not worth any appreciation. It is like listening to a nano chain-saw.

There might be a synonym between mosquito noise and any sound that does not comply with dominant standards of musical beauty. For example, Italian Futurist musicians such as Luigi Russolo’s were pursuing a similar family of sounds - machine sounds - as a way of defying the traditional aesthetic standards of the early 20th century.

When I hear the sound of machines and realize that we reject their noise in the same fashion as we reject a mosquito’s one (by not recognizing their “natural” beauty and classical standards of balance), it never fails to amaze me that we, as humans, deny the mosquitoes’ animality while putting them in a place where we feel entitled to act sadistically; killing them just for fun while feeling awesome as we do it. As humans, we have a similar sadistic impulse when we laugh at the humiliation of bad singers and musicians. Don’t be fooled: I’m not a pro-life mosquito activist; I’d kill one as quickly as you would, but the contribution of artists towards trivial or unwanted subjects might perhaps help us not to spend unnecessary and unpragmatic time with them but instead lure the public to observations that are not as superficial as everyday-life’s ones. Some souls will be moved and shook; some will have new sensations; some will leave exactly as they arrived in the exhibition room.

There might be a synonym between mosquito noise and any sound that does not comply with dominant standards of musical beauty. For example, Italian Futurist musicians such as Luigi Russolo’s were pursuing a similar family of sounds - machine sounds - as a way of defying the traditional aesthetic standards of the early 20th century.

When I hear the sound of machines and realize that we reject their noise in the same fashion as we reject a mosquito’s one (by not recognizing their “natural” beauty and classical standards of balance), it never fails to amaze me that we, as humans, deny the mosquitoes’ animality while putting them in a place where we feel entitled to act sadistically; killing them just for fun while feeling awesome as we do it. As humans, we have a similar sadistic impulse when we laugh at the humiliation of bad singers and musicians. Don’t be fooled: I’m not a pro-life mosquito activist; I’d kill one as quickly as you would, but the contribution of artists towards trivial or unwanted subjects might perhaps help us not to spend unnecessary and unpragmatic time with them but instead lure the public to observations that are not as superficial as everyday-life’s ones. Some souls will be moved and shook; some will have new sensations; some will leave exactly as they arrived in the exhibition room.

And that is what I did during my residency at Luleå University of Technology, where I was invited to create a work with their gigantic pipe-organ (link contains an interview where I explain my creative process). With the collaboration of young pianist and composer Sven Lidén, I made an electro-acoustic piece that was set-up as a sound installation at Röda Sten Konsthall in Gothenburg. “A Soul Transplant '' was a musical dialogue between mosquitoes and the pipe organ with synchronized theatrical lighting. Aesthetic power that turns into institutional power was the main aspect of it: while a church pipe-organ is a technological and institutional achievement that aims to carry you to Heaven and make you forget your worldly and physical pains, the mosquito is a vagabond, a nomad of insignificant strength that keeps reminding us of our bodies and our death.

Mosquito, an invertebrate militia

Back in my trip to Ghana, some of my local friends were talking about gentrification in Accra, their capital. They said that air conditioning was making the city much friendlier for tourists than when there was none. The heat was simply unbearable for people from colder countries. Now that most of their hotels and AirBnb flats have AC systems, they said that mosquitoes were the only thing preventing gentrification from completely taking over Accra, unlike the Ghanaians who are used to co-existing with them and their diseases.

That insight just stuck to my mind and probably won’t ever go away. Is there any social circumstance where the mosquito could “protect” people or “shield” a territory?According to J. R. McNeill in the book “Mosquito Empires” and Timothy C. Winegard in “The Mosquito: A Human History of Our Deadliest Predator”, it happened throughout history, at the cost of many lives.

That insight just stuck to my mind and probably won’t ever go away. Is there any social circumstance where the mosquito could “protect” people or “shield” a territory?According to J. R. McNeill in the book “Mosquito Empires” and Timothy C. Winegard in “The Mosquito: A Human History of Our Deadliest Predator”, it happened throughout history, at the cost of many lives.

[quote]In 1698, five ships set sail from Scotland, carrying a cargo of fine trade goods, including wigs, woollen socks and blankets, mother-of-pearl combs, Bibles, and twenty-five thousand pairs of leather shoes.[…] To make space for the luxuries, the usual rations for food and farming were reduced by half. But farming wasn’t the point. The ships’ destination was the Darien region of Panama, where the Company of Scotland hoped to create a trading hub that would bridge the isthmus and unite the world’s great oceans, while raising the economic prospects of a stubbornly independent kingdom that had just struggled through years of famine. The scheme was wildly popular in the desperate country, attracting a wide range of investors, from members of the national Parliament down to poor farmers; it has been estimated that between one-quarter and one-half of all the money in circulation in Scotland at the time followed the trade winds to Panama.

The expedition met with ruin. Colonists, sickened by yellow fever and strains of malaria for which their bodies were not prepared, began to die at the rate of a dozen a day. […] After six months, with nearly half their number gone, the survivors—except those too weak to move, who were left behind on the shore—returned to their ships and fled north. […] the expedition did have some lasting results: the overwhelming debt from the failure drove the reluctant Scottish to at last accept a unification offer from England. The mosquitoes of Darien led, by an unexpected route, to the birth of Great Britain.Jarvis, [[www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/08/05/how-mosquitoes-changed-everything reviewing Timothy C. Winegard]

The expedition met with ruin. Colonists, sickened by yellow fever and strains of malaria for which their bodies were not prepared, began to die at the rate of a dozen a day. […] After six months, with nearly half their number gone, the survivors—except those too weak to move, who were left behind on the shore—returned to their ships and fled north. […] the expedition did have some lasting results: the overwhelming debt from the failure drove the reluctant Scottish to at last accept a unification offer from England. The mosquitoes of Darien led, by an unexpected route, to the birth of Great Britain.Jarvis, [[www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/08/05/how-mosquitoes-changed-everything reviewing Timothy C. Winegard]

Mosquitoes changed demographic maps, ship routes and even urban distribution, avenues and neighborhoods in early 20th century Rio de Janeiro. Mosquitoes, a permanent tropical trait, clashes violently with imported ideals of modernization, urbanization and romantic visions of the Tropics.

Mosquito, the perfect villain

In Brazil, due to the diseases that mosquitoes can carry, governments and city municipalities have to create national and regional campaigns so that the population can turn into a civil army in order to fight the insects. For that to be effective, people have to hate or fear the mosquito even more. This is why marketing strategies usually use “unwanted” social profiles like criminals, murderers, prostitutes, the unemployed, homosexuals and bad singers to represent the mosquito. In this video, I connect the pre-16th century European fears of the “New World” to the recent anti-mosquito campaigns:

Mosquitoes and their hideous noise reveal with precision the need of different societies to anthropomorphize and aestheticize Nature as an attempt to understand and control it, as we have seen in the anti-mosquitoes campaigns mentioned in the video.

As any Art History student knows, representations such as those have a history and an origin of their own and as far as my research went, what became clear was that mosquitoes bring to the surface the pre-Modern fearful visions that represent the “New World” and its lack of Christianity, along with the current dominant ideals of health, cultural belonging and legality. There is a lot to this and I still have to distill this further. At some point, I will hide away in a hut in the snow or in a tropical forest to write about my contributions. In the meantime, please appreciate some studies:

Research-based art is also knowledge production and artists, in my view, are completely entitled to produce new knowledge through art. Art is a way to connect micro and macro visions of the world with acceptable clarity of where the artists stands in terms of place of speech, opinion and criticism towards certain subjects. In my opinion, it is always a pleasure to learn from artists because they usually have diverse standpoints that are not often found in Science.

While my own book isn’t written, please appreciate some studies that helped me put my ideas together:

As any Art History student knows, representations such as those have a history and an origin of their own and as far as my research went, what became clear was that mosquitoes bring to the surface the pre-Modern fearful visions that represent the “New World” and its lack of Christianity, along with the current dominant ideals of health, cultural belonging and legality. There is a lot to this and I still have to distill this further. At some point, I will hide away in a hut in the snow or in a tropical forest to write about my contributions. In the meantime, please appreciate some studies:

Research-based art is also knowledge production and artists, in my view, are completely entitled to produce new knowledge through art. Art is a way to connect micro and macro visions of the world with acceptable clarity of where the artists stands in terms of place of speech, opinion and criticism towards certain subjects. In my opinion, it is always a pleasure to learn from artists because they usually have diverse standpoints that are not often found in Science.

While my own book isn’t written, please appreciate some studies that helped me put my ideas together:

Other readings you might enjoy

Tropical Visions in an Age of Empire, Felix Driver & Luciana Martins

On Ugliness, Umberto Eco

Mosquito Empires: Ecology and War in the Greater Caribbean, J. R. McNeill

Remember Nature, Hans Ulrich Obrist & Kostas Stasinopoulos where I contributed with instructions for a mosquito listening session.

related events

related content

refered to from:

video – 20 sep. 2022